The British Film Institute (BFI) just released its Best Films of All Time poll for 2022 to much fanfare and self-congratulation among liberal whites. I can almost sense them patting each other on the back — or exchanging poorly executed high fives — for a job well done in ricocheting Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” from number 35, where is first appeared in 2012, to number 1.

First World Problems? Holding a mirror that looks today like a smartphone, Delphine Seyrig as Jeanne Dielman, as she prepares for “housework” in Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975).

This year’s poll marked the first time since 1952 when the once-a-decade poll was debuted that a woman topped the list of 100 films.

When I saw the announcement, I sensed a disconnection with reality by people who voted in the poll and thought they are making positive change. This reality is that the world is burning. I wondered about the state of field of film and media studies, if this poll is what administrators think those of us in the field do. It’s fandom and marketing, not scholarship.

I know people who refused to participate because they find such Best Films of All Time polls anti-feminist. This stance makes the victory of a film praised for being a feminist one all the more difficult to celebrate. The poll is marketed as a competition and hierarchy rather than cooperation and interdependence.

To make this observation, however, is not to imply that “Citizen Kane” or “Vertigo” should remain number 1. In fact, those films are outrageously sexist and incredibly boring. They were also made before the vast majority of the world’s population of 8 billion humans was born, which is not to say that all older films are completely irrelevant.

The attention to securing more representation for women is admirable, but the absence of white women who are actively critical of their own white privilege is spine chilling. Why have these films been chosen above all others by woman directors? There are ones that would not only make white women feel included without excluding all other women.

María Onetto as Verónica, the bourgeois dentist who stops after hitting an Indigenous boy, then continues, deceiving herself that he is no more than a dog, in Lucrecia Martel’s “La mujer sin cabeza” (2008).

The poll’s emphasis on best “of all time” is preposterous. Nothing endures forever. Nothing is forever relevant. The world changes, often to correct past errors. Lucrecia Martel’s “La mujer sin cabeza” (“The Headless Woman,” 2008), for example, reflects on how white women are guilty of violence against Indigenous people and nonhumans just like their white male counterparts. The film is absent from the list.

Visualization of the collateral damage of Whiteness on the most vulnerable in Lucrecia Martel’s “La mujer sin cabeza” (2008), which did not make the list.

Martel’s work references films like Grupo Cine Liberación’s “La hora de la hornos: notas y testimonios sobre el neocolonialismo, la violencia y la liberación (“The Hour of the Furnaces,” 1968), which pirated the deceptive power of Madison Avenue advertising to “decolonize the mind” from the lies manufactured by postcolonial élites as well as their Western imperialist enablers. She engages in film history but not on the level of aesthetics/style or auterism/fandom.

How is that films that are committed to making the world a more equitable and just place are so conspicuously absent on the BFI list?

What Is Wrong With Such Lists

In an era of institutional diversity schemes to whitewash the status quo, the list is conspicuous for its glaring exclusions.

The list contains only six films that are not from East Asia or Australia/Europe/North America — and that number includes Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” (1966) since the film was a collaboration with Saadi Yasef, though he is not credited under the auteurist idea of director.

The other five are Ousmane Sembène’s “La noire de…” (“Black Girl,” 1965), tied at number 95 with Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s “Tropical Malady” (2004) and several other films; Djibril Diop Mambéty’s “Touki-Bouki” (1973) at 66; Satyajit Ray’s “Pather Panchali” at 35; and Abbas Kiarostami’s “Close-up” (1989) at 11.

All of these films are connected to France, either through financing or through the mentorship of a French director.

There are no films from Latin America. There are also no films by Indigenous filmmakers.

Anyone with the slightest knowledge of conventional film history, as it has been written by Westerners, understands the list’s logic — and notices the absence of women beyond the eight white-Western women (Chantal Ackerman, Jane Champion, Véra Chytilová, Claire Denis, Maya Deren, Barbara Loden, Céline Sciamma, and Agnès Varda) and one (seems “token” since there are many) Black American woman (Julie Dash). No one else exists in such frameworks.

India has consistently produced more films than any place in the world, but it is reduced to Ray’s first feature film. Like many people, I adore the film and screen it in a class that I teach almost every semester. However, I contextualize it for how it was read at the Cannes Film Festival as a “human document” rather than an auteurist work of art like the films by white men and at the Flaherty Film Seminar as “ethnography” rather than an adaptation of a novel, performed largely by professional actors, and directed by someone who never lived in a village.

When a film seems like an outlier — the only film of a list of 100 from South Asia — there are reasons. “Pather Panchali” is set during British colonialism, gently criticizing its epistemological and physical violence. It doesn’t prompt Westerners to reflect on their inheritance of colonial violence as much as it might prompt upper-caste Hindus to reflect upon their unearned privilege.

I wonder why films like Deepa Dhanraj’s “Something Like a War” (1991), which critiques Indira Gandhi’s draconian policies of forced sterilization of mostly Muslim and Dalit poor rural women, funded by the Ford Foundation, is not included despite being distributed by Women Make Movies. Are so few of the voters aware of it?

A group of poor rural women with number tags affixed to their foreheads, as part of Ford Foundation’s efforts to control “overpopulation” in Deepa Dhanraj’s “Something Like a War” (1991), which is not included on the list.

Much like Affirmative Action in the United States disproportionately benefits white women, efforts to rebrand white-Western-serving institutions like this list are typically exercises in the reaffirmation of white supremacy.

They do not celebrate overt racist violence, but they do not challenge the covert racist violence with attention to anticolonial, postcolonial, and decolonial critiques of the Western Enlightenment’s equality for “Man,” later opening to include white women, then everyone else who hadn’t been recognized as human.

As BIWOC activists and scholars have reminded us since long before 1952, white women were complicit with slavery and servitude. White women in the United States could own slaves before they could vote.

Liberalism Has Always Been Insufficient

The Enlightenment concept of liberalism is sometimes difficult for white people to critique since it sounds as though it should benefit to everyone but it rejects so many alternative ways of being.

I am not thinking of conservatism, often assumed to be the only alternative to liberalism, according to the bipolar thinking that dominates so-called democratic republics.

I am thinking of ways of being that acknowledge mutual responsibility to all humans on the planet and also to all nonhumans. Privileged humans need to recognize that humans are part of nature, not overlords over nature. As a species, we have a responsibility to ensure that clean air and water are available to everyone. We also have a responsibility to allow the most vulnerable whether human or nonhuman, to live with dignity.

We need stories that are more capacious than one about a white woman sitting in the capital of one of the most cruel and inhumane empires. Jeanne Dielman is no more a universal signifier of humanity than Charles Foster Kane or “Scottie” Ferguson.

If the 2022 poll is supposed to signify progress, then we have moved from 1941 or 1958, when “Citizen Kane” and “Vertigo” were produced, to 1975 when Ackerman made her film.

By the mid-1970s, the former Belgian colonies of Burundi, Congo, and Rwanda (using their present names here) had experienced decades of civil war and genocide — and would continue to do so. The reasons are bound to King Léopold’s extraction of life, resources, and wealth that financed Dielman’s boring bourgeois Belgian life more than her sex work. Ackerman’s film is not feminist unless it acknowledges that the patriarchy Dielman experiences as oppression is a shared one with others who have suffered much more. Patriarchy binds capitalism, colonialism, imperialism, and consumerism.

Without detracting from Ackerman’s film, it is noticeable that Jean-Luc Godard’s “2 ou 3 chose que je sais d’elle” (“Two or Three Things that I Know about Her,” 1967) is absent from the BFI list. Godard’s other less political work is included, but his analysis of white women prostituting themselves in order to afford a postwar middle-class lifestyle is absent. The film situates this phenomenon within the context of imperialism and its violence on bodies beyond the white women, who deposit their children for daycare as they exchange sex for money — which is not to say that Godard was above sexism.

White women perform dehumanizing commodity fetishism before the proverbial male gaze, as a nod to cultural imperialism’s connection with imperial wars, in Jean-Luc Godard’s “2 ou 3 chose que je sais d’elle” (1967), not on list.

Celebrating the film as number 1 can seem like a throwback to single-issue feminism, a backlash against the hard work of BIWOC who mostly could not make feature films, particularly at such a young age as Ackerman. Weren’t Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen taken to task on this very problem in their “Riddles of the Sphinx” (1977)?

Julie Dash is the only not-white woman in the list. But her landmark film “Illusions” (1982), which deconstructs systemic racism, is absent. Instead, her “Daughters of the Dust” (1991), whose cinematography and mise-en-scène likely bedazzled BFI voters from seeing its searing critique of systemic racism, is there.

Rosanne Katon as Esther Jeter in Julie Dash’s “Illusions” (1982), which did not make the list but reveals the Hollywood movie magic of concealing Black labor to create the illusion of white talent.

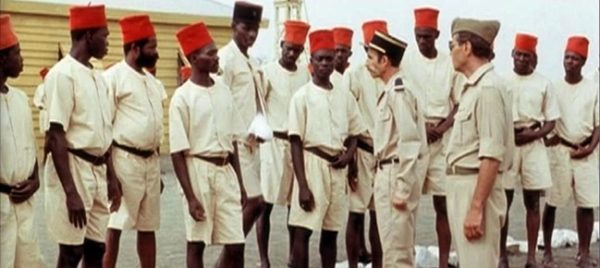

The only films by African filmmakers concern the violence of internalized racism. I hold both “La noire de…” and “Touki-Bouki” in highest respect, but I wonder why other films are not included, such as “Camp de Thiaroye” (1988) in which France, the great republic that promised to “civilize” the world, slaughters soldiers who served its army and helped save it from the Nazis. And where are films by Safi Faye and Sarah Maldoror, if the list’s prerogative was to foreground women?

African soldiers in the French army greet white commanders, awaiting compensation that will come in the form of bullets rather than cash, in Ousmane Sembène’s “Camp de Thiaroye” (1988), also not on list.

Sembène and Diop Mambéty, I believe, are also the only Muslim directors to make the list. How is this possible?

Two decades after 9/11, we know that George Bush II and Tony Blair used phantom WMDs as a dog-whistle for Islamophobic racism to garner populist support for violent military interventions. Shock-and-awe was an inhumane form of collective punishment that resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of civilians including children for the fortunes of government insiders. How are the critics and educators who participate in this poll not able to recognize that films by Muslims are worthy of inclusion?

These “Best Films of All Time” lists celebrate infantilism with a willful retreat from reality into a plush echo chamber. Yes, it was remarkable for Ackerman to make a film with an all-female crew. But, no, the film is not unequivocally better than her mature work, particularly her documentary “Sud” (1999).

Critics smile about the coincidence that Ackerman made “Jeanne Dielman” at age 25, the same age as Orson Welles when he made “Citizen Kane.” This attitude reinforces mythologies of talent. They do not reflect that these films might also convey immaturity. It seems like a retreat into childish irreverence for others.

Why This List Needs to Be Replaced

BFI’s Best Films of All Time poll was inaugurated in 1952. We need to ask ourselves whether anything from 1952 that includes the word “best” is really worth preserving.

Colonial and imperialism paraded as benevolent tutelage. Women’s rights were limited, as were ones from most not-white (not a typo for non-white) people in the so-called West which basically functioned as imperial metropoles. The world has changed phenomenally over seven decades. It would no longer be recognizable to the white men who voted in the early polls.

In 2022, surely, we have collectively realized that imposing a singular definition of “best” is both highly prejudiced and counterproductive to collective survival.

If the 2022 poll has almost completely erased films from countries producing the largest number of films today, such as China, India, and Nigeria, can it really be taken seriously? Does is not automatically fall into the category of white-Western imperial nostalgia? And what might be behind this nostalgia?

About 20 years ago, articles by cinéphiles bemoaning the “death of cinema” with the arrival of digital cameras littered the pages of the BFI’s “Sight & Sound” and other magazines. Yet these digital cameras allowed people without economic and social privilege to convey their own perspectives. Could opening cinema to such perspectives been what these cinéphiles might have also implied by crying over cinema’s death?

This universalized conception of “cinema” sounds like a reason to remind everyone that Western empire has an expiry date like every other empire. When used to describe films, the term becomes a lofty and uncritical nostalgia for a particular kind of filmmaking, a kind that cannot be streamed or watched in ciné-clubs on an old rayon-tube television in a city or town where commercial cinemas do not exist. It hinges on an arrogance that everyone has or should have access to a nicely appointed cinema with 35mm projectors and Dolby surround sound were the world not incumbered by gross inequities and injustices.

This sort of thinking is precisely what needs to be decolonized. It weaponizes taste, a well-known tactic of domination in postcolonies and settler colonies.

Learning from the Rhodes Must Fall movement in South Africa, I speculated on a potential #OscarMustFall movement in an article originally published in Jump Cut and republished with a new appendix by the African Film Festival. I issued a call hoping that film critics, distributors, educators, exhibitors, and makers might join together in solidarity to provincialize Hollywood and deprovincialize the world.

Oscar defines merit as something only available to people who benefit from industry nepotism and unearned social advantages. We need to reject the arguments by Oscar apologists that “movies” are just entertainment.

It is fine to consider not-Western filmmakers whose work translates to Westerners such as Abbas Kiarostami — or Asghar Farhadi, who work didn’t make the BFI list but often is nominated for Oscars. However, filmmakers critical of this system also need to be included.

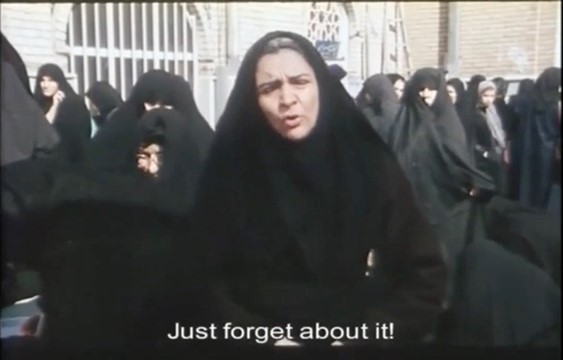

Rakhshan Bani Etemad’s “Under the Skin of the City” (2001) examines the instrumentalization of religion by an oppressive regime and the slow violence of Western economic sanctions, as they entangle women and men in a suffocating reality that has lasted for four decades. And where is Forough Farrokhzad’s “The House Is Black” (1962), available from Facets, an arthouse distributor?

Golab Adineh as Tuba, calling out filmmakers for making images that affect nothing for the people who are suffering, in Rakhshan Bani Etemad’s “Under the Skin of the City” (2001), not on list.

And where are films by Arab filmmakers? Colleagues bemoan how Arab film is so often reduced to Youssef Chahine’s work, yet not a single of his films appears on the list. Nor do ones by Arab women, such as Ateyyat El Abnoudy, Asma El Bakry, Khadija Habashneh, Mai Masri, Jocelyne Saab, Heiny Srour, and Moufida Tlatli.

Other films open up thinking about issues dropped from the list’s priorities. Arlene Bowman’s “Navajo Talking Picture” (1986), for example, explores the obstacles against Indigenous people from telling stories. Bowman cannot communicate with her own grandmother since she cannot speak Navajo. She has to hire an interpreter. Her grandmother simply does not think that films are compatible with her way of being.

The filmmaker begins to realize that she is imposing a kind of violence on her own grandmother in Arlene Bowman’s “Navajo Talking Picture” (1986), also not on list.

Not all epistemologies can be documented and screened to outsiders, an important part of Indigenous media. Universalism and mass audiences are fantasies. Bowman’s film is available from Women Makes Movies, a feminist distributor now celebrating its 50th year — without many films by Muslim women but loads about Muslim women, if I may be honest.

What We Might Do

I write this criticism of the BFI list as someone who actually appreciates the institution.

BFI’s Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire is an amazing resource. It includes digitized films impossible for most people to access otherwise with detailed notes. As someone who teaches film and new media studies, they are invaluable. I also appreciate the BFI’s commission of filmmakers such as Sandhya Suri to reedit archival materials into compilation films.

Suri’s “Around India with a Movie Camera” might be entangled in efforts to forget the restitutions that Britain owes India and the rest of South Asia for the damage inflicted and resources extracted. But it foregrounds the arrogance of Western colonialism and the possibility of locating Indian refusals to submit to it. Suri slows down and loops an image of the Gaekwar of Baroda (Maharajah Sayyaji Rao III) breaking protocol as Britain’s King George V and Queen Mary coronated themselves emperor and empress of India. They grifted the form of a durbar (state reception) to present themselves as heirs to the Mughals, a form of self-delusion they share with today’s rightwing Indian political party in power.

The Gaekwar of Baroda refuses to bow to King George V and Queen Mary at a durbar to coronate themselves emperor and empress of India in 1911, pirated in Sandhya Suri’s “Around India with a Movie Camera” (2017).

As I argue in a forthcoming article in “Social Research,” Suri “pirates” (borrowing the term from Patricia R. Zimmermann’s “States of Emergency”) the archive. She reflects critically on the arrogance of King George who had the audacity to crown himself Emperor of India and the arrogance of Narendra Modi who has mainstreamed Hindutva (Hindu nationalism), resulting in violence against Muslims, Dalits, Adivasis, and others.

White female missionary pats Indian women on head for surrendering her jewelry to Jesus, in a staged scene for a colonial film, pirated in Sandhya Suri’s “Around India with a Movie Camera” (2017).

Why don’t we pirate these Best Films of All Time lists? I suspect that the BFI conducts the polls for screening income on its website and to attract subscriptions to its magazine “Sight & Sound,” which I do read. My initial paper-only subscription was a gift-to-self for finishing my Ph.D. and getting a job. I also purchased an Afghan rug from a shop going out of business and parts to build a plasma-screen television. It was an extravagance at the time.

I have seen some of the backlash against this year’s list on social media. Angry young men sulked that BFI has pandered to appearing “politically correct,” a racist dog-whistle against social justice. Angrier middle-aged and old men did as well. They also whined that Jordan Peele’s “Get Out!” is undeserving. The film deserves a top spot precisely for eliciting that reaction.

To address the inevitable collateral damage of these polls, which is that the list continues to perpetuate a narrow definition of what is “best” and what counts as “cinema,” I think everyone who has the financial means should subscribe to the magazine and send an email to Editor-in-Chief Mike Williams and/or Managing Editor Isabel Stevens to suggest this poll be reworked.

Why not ask the most privileged to step outside their insular and navel-gazing ways to consider other people?

We are barraged daily with news of climate catastrophe, economic and environmental refugees, ecosystem collapse, market orthodoxy, mass species extinctions, neoliberal surveillance with big data, populist neofascism in Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Florida’s Ron DeSantis — not to mention Narendra Modi’s instrumentalization of decolonization towards fascist ends in India — privatization of basic services, religious fundamentalisms, especially in the West, rogue billionaires, and unsustainable extraction of natural resources. There are attacks on women’s rights in the United States, attacks on LBGTQ+ rights in Russia, and attacks on citizens in China, Iran, Israel, and elsewhere.

Why not build a constellation of BFI lists for 2023 that move away from an undefined concept of “best” to produce useful compendiums of films that address these crises and the inequities and injustices that they produce?

Dale Hudson is an associate professor at New York University Abu Dhabi. His research and teaching focus on environmentalism and on film and visual media in Southwest Asia, North Africa, and South Asia. He is co-author of “Thinking through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places” (2015), author of “Vampires, Race, and Transnational Hollywoods” (2017), and co-editor of a double issue of “Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication” on “Film and Visual Media in the Gulf” (2021) and “Reorienting the Middle East: Film and Digital Media Where the Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, and Indian Ocean Meet” (forthcoming, 2023). He programs exhibitions for the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF) and coordinates Films from the Gulf for the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) Film Festival.