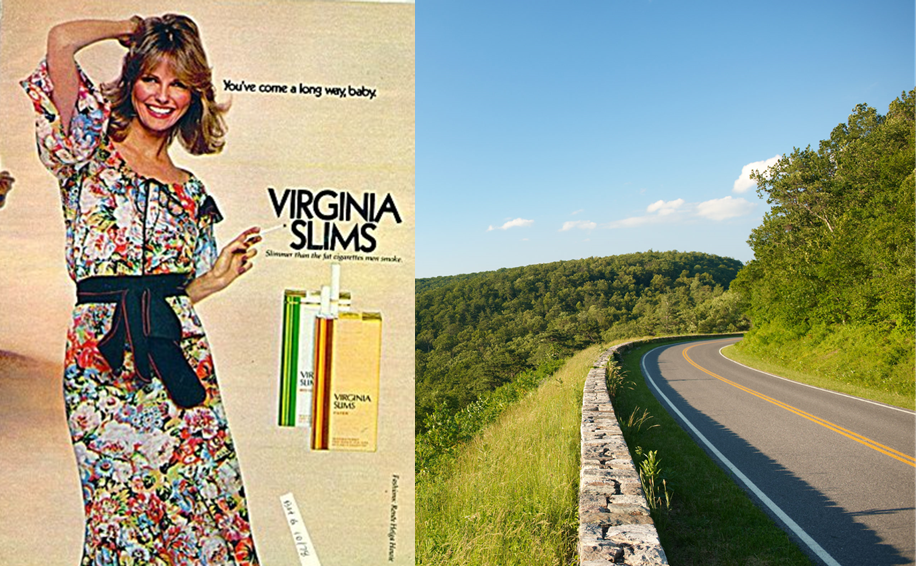

During my childhood, the only association I had with Virginia was cigarettes, as in Virginia Slims, a brand that promoted smoking as a form of glamorous liberation for women long after we knew cigarettes were deadly. That slogan was “You’ve come a long way, baby” and always featured a sexy young woman with a Virginia Slim in her long, manicured fingers. The ad told us this cigarette was slim like her, not like the bigger ones made for men, thereby confirming women as diminutive to men and surely unattractive if they were not as skinny as a cigarette. The slogan, not unironically, capitalized on the feminist movement of that time. It implied that dressing fashionably and smoking a cigarette named after the state where tobacco plantations began — plantations that fostered slavery, servitude, and the depletion of the soil’s nutrients — meant a woman (aka a baby) had finally arrived.

The next time I heard the word “Virginia” was in the slogan “Virginia is for Lovers.” To a young girl this meant that there was something highly romantic about Virginia. Later, I looked for that romanticism when I went to grad school in nearby Washington, D.C. There were mountains, rivers, and lakes that took my breath away but people didn’t look like they were particularly in love. My media professor explained it wasn’t that kind of love. The 53-year-old slogan had started out as “Virginia is for History Lovers” because this is where the American history narrative was created and celebrated through national landmarks — Mount Vernon (George Washington’s home), Monticello (Thomas Jefferson’s home), Colonial Williamsburg, the battle of Yorktown and so on. Richmond, Virginia’s capital, was the capital of the Confederacy. Lovers of a white-washed history could certainly love Virginia.

I am in Virginia now, arriving here after a near five-year absence from the U.S. During my unintended exile (COVID, etc.), I had missed my friends and family — and the glorious trees and landscape of this country. I had also missed the Trump presidency, the George Floyd murder and its aftermath in my home state of Minnesota, the white supremacist “rally” in Charlottesville, politicians causing panic by throwing around words like critical race theory without knowing what they mean, and the acceleration in mass shootings, the opiate crisis, the rich and poor divide, and housing prices (well, all prices).

I landed in Virginia the day Roe v. Wade was overturned. As the news played on the airport monitors, all I could see in my head were those Virginia Slim ads, which likely profited from what Roe v. Wade said about women owning their own bodies to do as they saw fit — whether that meant reproductive rights or smoking. So have we come a long way, baby? While the abortion debate in large part revolves around when a fetus is a baby, a woman is apparently still a baby, no matter how far along she has come — and other people get to decide what is best for her again. Even statement songs of that 1970s feminist era, like Helen Reddy singing, “I am woman, hear me roar” play like parody now.

There are no more Virginia Slims ads, a victory for women and human health. (More Americans smoke marijuana today than cigarettes.) In the state where the Supreme Court had to interfere to allow for interracial marriage in 1967, the many mixed couples holding hands at the beach today doesn’t cause anyone to turn their heads. Sally Hemings is recognized as Thomas Jefferson’s slave and mistress at Monticello. It can make you believe that Virginia is indeed for lovers, especially as the slogan is still abundantly available on license plates.

Today, when I drive along Virginia’s highways and sit in its restaurants, the signage is sometimes about cigarettes. But mostly Virginia’s signage is for lovers of lawyers, guns, and Jesus, a somewhat incongruous trinity. There are also American flags everywhere, unabashed nationalism. Flags appear on pick-up trucks and people’s tattoos, which I now view as individual pop-up ads, depending on what body parts are being revealed to me.

Before I saw the Roe v. Wade news on the airport monitors, a man shouted out to me, “Take off your mask. You’re in America now.” I thought, doesn’t the Bible say love — embodied by Jesus of the billboards and bumper stickers — is patient and kind?

Instead, all this signage (and occasional shouting), personal and public, speaks of fear. A tip about a planned mass shouting in Richmond took over headlines on Independence Day. The TV news reporters stirred up panic in their coverage. What is independence if fear exists? When I look at the billboards and signs now, I think, “Where is the road taking us, people?”

Alia Yunis has worked as a filmmaker and writer in many parts of the world. Her feature documentary, “The Golden Harvest,” is currently in film festivals. Her fiction, including “The Night Counter” (Random House), and non-fiction writings have appeared in numerous books, magazines and anthologies and have been translated into eight languages. She is a visiting associate professor at New York University Abu Dhabi.