The recent emergence of what has come to be called the video essay or the videographic essay or the audiovisual essay represents a new cinematic avant-garde. It offers implicit and explicit critiques of both commercial media and the logocentric literature of academic cinema and media scholarship.

What are the historical roots of the video essay as critique?

In 1975, Peter Wollen published his canonical essay, “The Two Avant-Gardes,” which focused on two traditions of European cinema, each of which offered an ongoing critique of the forms of entertainment cinema epitomized by Hollywood.

On the one hand, there were filmmakers who abjured industrial film production and identified with the world of modern art. Instances include Hans Richter (“Rhythmus 21,” 1921) and Viking Eggeling (“Symphony Diagonale,” 1921-23), who explored visual abstraction; Dadaists Man Ray (“Retour à la raison,” 1923) and Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy (“Ballet mécanique,” 1924); and surrealists: Germaine Dulac in “La coquille et le clergyman” (1928) and Luis Buñuel/Salvador Dalí (“Un chien andalou,” 1929; “L’ag d’or,” 1930).

The range of eye-opening approaches established by this early avant-garde was enlarged decades later by filmmakers who in various ways were working in modes inspired by their predecessors, including Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Sidney Peterson, Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Bruce Baillie, Marie Menken, Jack Smith, et al.

Wollen’s other avant-garde tradition included European film directors who made feature narrative films that offered clear alternatives to Hollywood genre filmmaking, including Jean-Luc Godard, Straub-Huillet, Luis Buñuel, Miklos Jansco, and in a somewhat different sense, the Russians, Eisenstein and Vertov.

Of course, many filmmakers from various cultures exploited the broadening of approaches that these two avant-gardes developed. Wollen himself collaborated with Laura Mulvey to produce “Riddles of the Sphinx” (1977), a feature constructed to bring the two avant-gardes together into a single film where an experimental narrative, “Louise’s Story Told in Thirteen Shots,” is surrounded by triads of short films, each evoking an approach familiar from non-narrative forms of avant-garde cinema.

During the half-century since Wollen’s essay was published, our awareness of the geography and history of cinema has undergone an immense expansion. The evolution of new technologies for making and presenting motion pictures has contributed to this development as well as the increased access to the ever-expanding archive of film history.

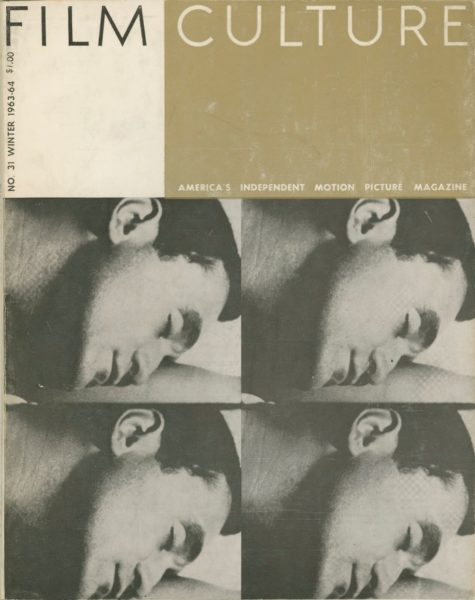

There were many accomplished filmmakers working outside of commercial industries in the 1940s-1950s, but for an American avant-garde cinema movement to develop during the 1960s more was needed. It required the pioneering efforts of particular individuals, the development of a community of makers whose work was in conversation, and new opportunities for making work available to the public and for expanding that public. The pioneering efforts of Amos Vogel and Frank Stauffacher in generating an American film society movement and in Vogel’s case beginning to distribute prints of avant-garde films were followed by Jonas Mekas’s many contributions beginning with the journal Film Culture (1954-1996).

In 1960 Mekas rallied filmmakers working outside the Hollywood industry to form what he termed the New American Cinema. He subsequently established the New York Film-makers’ Cooperative to distribute their films. It was quickly followed by the Bay Area’s Canyon Cinema. Mekas wrote pro-avant-garde polemics in The Village Voice and the SoHo Weekly News and helped establish Anthology Film Archives as a permanent home for alternative cinemas.

Mekas’s efforts helped make the avant-garde of the 1960s a force in contemporary filmmaking and to some extent within academe which was just beginning to include cinema studies. SUNY-Binghamton (now Binghamton University), the San Francisco Art Institute, and SUNY Buffalo (now the University at Buffalo) became centers for avant-garde filmmaking.

To a considerable degree the video essay is the child of avant-garde film history, which includes a range of premonitions of the essay film, including Chris Marker’s “Letter from Siberia” (1957) and “Sans Soleil” (1983), Morgan Fisher’s “Standard Gauge” (1984), Su Friedrich’s “Damned If You Don’t” (1987), and Jonathan Caouette’s “Tarnation” (2003).

Emerging scholars of the video essay have tended to name other premonitions. In her “The Audiovisual Essay as Performative Research” (NECSUS, December 4, 2016), Catherine Grant focuses on Ian Garwood’s “The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism” (2016); Domietta Torlasco’s “House Arrest” (2015); and Will Booker and Rebecca Hughes’ “Bowie Bowie” (2016), three very different video essays, suggesting the considerable diversity of approaches by 2010.

Like the 1960s-1970s American avant-garde, a video essay movement has required pioneering figures. Jason Mittell has mentored a generation of video-essayists at Middlebury College. His video essays and those of Catherine Grant have been formative for the field. With Christian Keathley (also at Middlebury), Mittell and Grant wrote the formative text, “The Videographic Essay: Practice and Pedagogy.” They created the online journal “[in]Transition,” where noteworthy instances of the video essay are published.

In 2022, Lever Press, an online publishing adventure that Mittell helped found, announced that the press would be publishing “Videographic Books,” hoping to expand the idea of the scholarly video essay as an alternative or addition to the scholarly written essay. This project will include long-form scholarly undertakings that seem likely to help us understand dimensions of cinema that the scholarly prose of a book cannot fully comprehend.

And just as Mekas’s early Voice columns helped promote avant-garde accomplishment, Will DiGravio’s video-essay podcasts are bringing increased attention to many video-essayists and their work.

Over the decades, American avant-garde filmmakers have depended on screenings hosted by a network of film societies, museums, colleges and universities and on dedicated distributors such as the New York Coop, Canyon Cinema, New York MoMA, and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre to manage the films and share the rental money. They also depend on grants from local and state arts councils. For example, the New York State Council on the Arts has provided funding for many filmmakers.

In contrast, video-essayists/scholars do not rent their work. Video essays tend to be labeled “for study purposes only” or “for research purposes only.” They are not for profit and so remain outside of rights issues for the quotations from earlier media they use. Most video essays, including all those referenced here, can be experienced on any viewing/listening platform as well as theatrically at no cost.

Among the most significant and distinctive contributors to this new avant-garde especially within the America/European movement is Chloé Galibert-Laîné. Early in 2022, the filmmaker J. P. Sniadecki suggested that I access Galibert-Laîné’s “Forensickness,” a 41-minute video essay focusing on Chris Kennedy’s “Watching the Detectives” (2017), a short 16mm feature about Reddit postings by redditors trying to solve the Boston Marathon bombing of 2013. At the time, I had not heard of Galibert-Laîné, or even of the video essay as a new form (or for that matter, Chris Kennedy!). I was fascinated.

Galibert-Laîné’s work combines a considerable range of formats, sources, and modes of text, image, and audio to demonstrate how media-making can function as a form of cinematic research that leads to new kinds of scholarship, accessible and engaging not just for experts but for a general media-interested audience.

Her researches have often explored films by filmmakers who have been understood as contributors to art-world avant-garde cinema such as James Benning, and Chris Kennedy as well as filmmakers like Peter Watkins and Georges Franju, whose films fit into Wollen’s narrative-feature avant-garde. Galibert-Laîné’s video essays also explore cinema-spectatorship itself.

Much of Galibert-Laîné’s work is online at her website. I particularly recommend “Reading//Binging//Benning” (2018), made with Kevin B. Lee, another important figure in the emergence of the video essay; “Watching The Pain of Others” (2019), instigated by Galibert-Laîné’s experience of walking out of “Penny Lane’s The Pain of Others” (2018) at the Rotterdam Film Festival; and “A Very Long Exposure Time” (2020), a poetic short that braids together a range of photographic, cinematic, and digital forms of duration. “Forensickness” and “Watching The Pain of Others” were two of three sections of Galibert-Laîné’s PhD thesis (the third, an extended essay written in French).

The American/European Video Essay movement has emerged from academia, largely at the hands and minds of teachers/scholars rebelling against the traditional assumption that serious scholarship must be written and printed in peer reviewed essays and books. However, other makers whose work has contributed to the evolution of the video essay have entered the field from other directions.

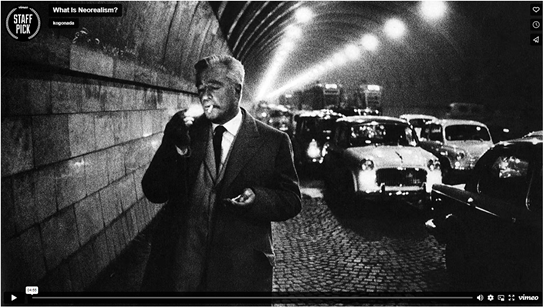

The Korean-born American filmmaker Kogonada has often followed in the footsteps of the American montage artist Chuck Workman’s “Precious Images” (1986) and “Pieces of Silver” (1989). He makes engaging, implicitly revealing, sometimes-sponsored video essays out of clips from well-known, usually popular films such as “Kubrick//One Point Perspective” (2012), “Malick//Fire and Water” (2013), “Eyes of Hitchcock” (2014), “Hands of Bresson” (2014), “Godard in Fragments” (2019). He has also produced more contemplative video essays.

In “What is Neorealism?” (2013), Kogonada compares two edits of the same 1953 film, one by Italian director Vittorio De Sica (“Terminal Station”) and the other (“Indiscretion of an American Wife”) by Hollywood producer David O. Selznick. The comparison reveals the differences in the filmmakers’ fundamental assumptions about how cinema works to tell stories and to represent reality.

In “The World According to Kore-eda Hirokazu” (2013), Kogonada’s exploration of the Japanese filmmaker’s work is powerfully moving, both a beautiful film in its own right and, like Galibert-Laîné’s “Reading//Binging//Benning” and “Watching the Pain of Others,” an insightful celebration of an admired colleague that alerts any viewer not familiar with Kore-eda to the nature and significance of his oeuvre. Like Galibert-Laîné’s video essays, Kogonada’s are available online at his website.

The remarkable avant-garde movement of the ’60s and ’70s transformed not only film history but the nature of how cinema is taught in many colleges and universities. It remains to be seen how much the new avant-garde of the video essay will transform the teaching of cinema. It’s already clear, however, that its easy availability online solves what was the earlier avant-garde’s biggest problem: you had to find your way to places willing to project it (and you still do).

As you read this, you’re already looking at a primary source for experiencing video essays. The necessary technology is at your fingertips!

Scott MacDonald is author of “A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers” (5 volumes, California), “The Garden in the Machine” (California, 2001), and 14 other books, most recently “Avant-Doc: Intersections of Documentary and Avant-Garde Cinema” (Oxford, 2015); “The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama” (Avant-Doc 2) (Oxford, 2019); “William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission” (Columbia, 2020) and “Comprehending Cinema” (Avant-Doc 3) (forthcoming). Named an Academy Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2011, he teaches film history and programs F.I.L.M. at Hamilton College.