The continuing Russia-Ukraine War demands new ways of thinking both about media coverage that seeks to inform in real time and new strategies about how to document it in order to build alternative archives.

For instance, the news coverage of the Russia-Ukraine War falls into three distinct categories.

The first is Western mainstream coverage of the war by CNN, the BBC, and other transnational news companies, where reporters stay for short periods, often do not speak Ukrainian or Russian, and rely on fixers, translators/advance personnel to make introductions and smooth the way. The problem is that reporters see and hear what the fixers want them to see and hear.

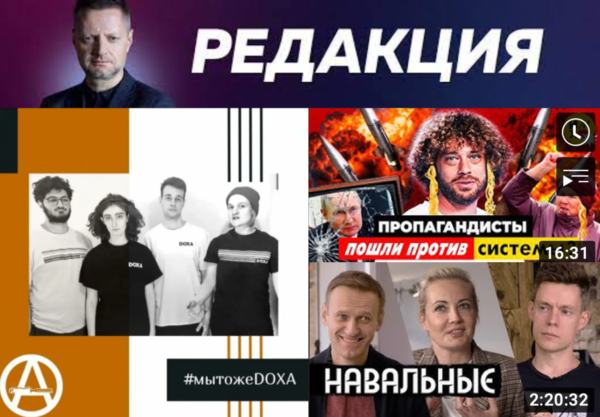

The second is the Russian opposition’s coverage of the war on YouTube channels such as Aleksei Pivovarov’s Redaktsiya News, Yuri Dud’s and Ilya Varlamov’s personal channels, and the former main opposition TV station, Dozhd’. The student-run DOXA magazine, initially focused on Russian higher education, quickly moved into student human rights activism. It has now also emerged as a leading source of war news, disseminated primarily on Instagram.

Clockwise: voices of the Russian opposition – journalist Aleksei Pivovarov, YouTube sensations Ilya Varlamov and Yuri Dud (interviewing Alexei and Yulia Navalny before Alexei’s arrest), and the previously jailed and now in exile editors of the student-run DOXA magazine.

The third is Ukrainian media coverage consumed by Ukrainian and diaspora audiences primarily via channels on the Telegram secure messaging app.

Organizations falling in the last two categories seek to communicate accurate information about the latest news in as close to real time as possible on social media platforms.

Now, Ukrainian filmmaking collectives are also thinking about how to create archives of the war for posterity.

These archives have three critical functions. They provide evidence of war crimes. They preserve source materials for future historical accounts. And, in a war perceived as a standoff between Russia and the West, they establish a case for the agency of everyday Ukrainians.

The impulse to document has origins in World War II, when the Soviets deployed 258 camera operators dispersed along their frontlines. Currently in Ukraine, a similar strategy to document the war in detail is taking place.

Camerawoman Ottilia Reizman in Budapest, 1944. Photograph from the 2015 exhibition at the French Holocaust Memorial titled: “Filmer la guerre: les soviétiques face à la Shoah (1941-1946).”

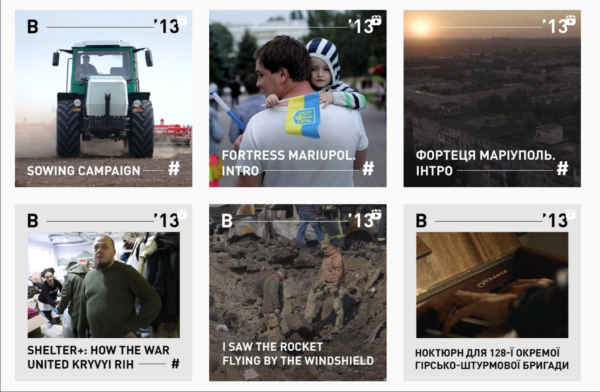

Two collectives, Babylon’13 and Freefilmers, have been producing, gathering, editing, and disseminating footage. They operate anonymously, pool what they’ve produced, and distribute their videos online a few weeks after they have been shot.

Their main channels of distribution are YouTube, Instagram, and Telegram, though Babylon’13 occasionally posts to TikTok, Twitter, and, in an attempt to reach Russian audiences, the Russian-language version of Facebook, VKontakte. Each channel reaches different audiences — young and old as well as English, Ukrainian, and Russian speakers.

Babylon’13

The Babylon’13 collective is the first, largest, and most prominent grassroots independent media organization in Ukraine, with 119,000 followers on YouTube.

The collective got started during the 2013-2014 protests against Ukraine’s corrupt pro-Putin regime on the main square in Kyiv, which came to be known in Ukrainian as “The Maidan” and in English as “The Revolution of Dignity.” The protests erupted when President Yanukovych decided not to sign a free trade agreement with the European Union (EU). The collective wanted to encourage more people to join the movement by showing what was really happening in the square and to counter misrepresentations in international mainstream news.

Within a few weeks, the collective counted over 50 members. Eventually, they uploaded more than 300 videos of the protests and the ensuing fighting. On their website, Babylon’13 stated their intention to “memorialize and showcase the birth and first decisive steps of civil society in Ukraine.”

Babylon’13 has developed a distinctive approach. In the mission statement on their website, they profess faith in documentary as “a tool that is able to change people’s perception of reality.” They adopt an observational style, with subjects occasionally addressing the camera directly. The videos avoid commentary or voice-over, marshalling a detail-rich, location-specific, “you-are-there” alternative to the evening news.

Babylon’13 is mindful of their mission as historians of Ukraine, presenting a history that emerged apart from official sources and Western mainstream media biases.

In 2014, the group was among the first to document the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbass.

In 2018, the collective handed over 300 hours of footage to the then recently established Maidan Museum in Kyiv.

In 2021, they released a historical series on their YouTube channel, where a young historian explains — presumably to younger audiences — how the Maidan unfolded, using clips from the group’s videos.

In the years between the Maidan and the present, many members — all volunteers — dispersed.

However, when Russia invaded on February 24, 2022, almost all became active again.

The collective has also drawn in new members. Volodymyr Tykhyy, who coordinates the collective’s efforts, estimates that around 80 people are currently involved. A dozen serve as video directors. The rest help with producing, editing, and logistics. An army of translators, many living abroad in the diaspora, add English and Russian-language subtitles to the videos.

Since the start of the war, the collective has uploaded over 150 videos from one to ten minutes in length. In the early weeks of the war, many videos reedited found footage provided by family and friends. As the situation stabilized, the collective’s members resumed shooting with higher production values.

In a piece written a few months ago for Docalogue, Masha argues the videos fall into four distinct categories.

The first is uplifting profiles of everyday people utilizing their professional skills to aid the war effort. These include videos about a train conductor who has worked dozens of trips on the evacuation trains, sculptors making portable heaters, and an icon painter who creates paintings to send to the front.

The second category presents labor apart from combat, such as volunteers sorting, storing, and distributing humanitarian aid, regular citizens covering monuments in sandbags in anticipation of bombing and occupation, and clean-up crews in recently liberated towns.

The third category focuses on efforts to aid vulnerable populations such as children, Roma, other civilians, and both the human and animal residents of the Kyiv zoo.

The fourth category documents the extent of the desctruction. This group includes videos taking stock of the damage in cities such as Borodyanka, Bucha, and Irpin.

Despite intensive efforts, the collective has not been able to embed with the Ukrainian Armed Forces. They secured access only once producing a heartbreaking video of Ukrainian forces waiting to ambush a Russian tank column. At the end, the film explains that Yuri Oleynik, the video’s protagonist and a cinematographer who volunteered for the Army, was killed.

Who Watches?

The question of audience and impact is critical for Babylon’13.

The Maidan videos of 2013-2014 were shot primarily for a domestic audience and were then morphed into a teaching archive.

The videos of the war feature playlists in English, Ukrainian, and Russian. Though Ukrainian- and English-speakers are the main target audience, the playlist subtitled in Russian suggests an attempt to pierce through the Russian state propaganda apparatus.

Because the carefully curated videos are generated only by members, Babylon’13 does not function as a democratic, user-generated, dispersed “archive from below.”

Nevertheless, as Dale Hudson and Patricia Zimmerman argue in Docalogue, Babylon’13 produces a “polyphony of voices from multiple regions” that counter Russian claims about Ukrainian nationalism by showcasing the diversity of Ukraine. Their videos confront both Russian misinformation and Western voyeurism — what Hudson and Zimmerman describe as the “distancing tropes of CNN and BBC.”

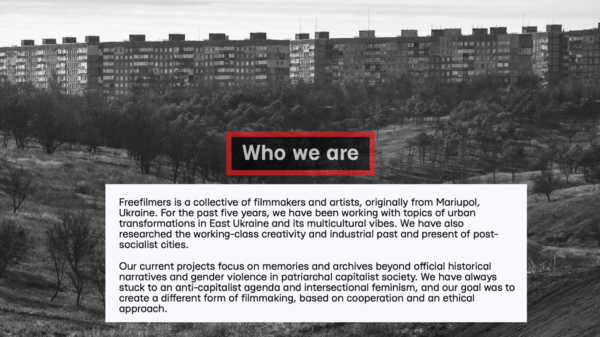

Freefilmers

Freefilmers is another media collective of artists and filmmakers. Like Babylon’13, it was initially based in a single city — in Freefilmers’ case, Mariupol. Most of the filmmakers fled when the city was occupied by Russian forces. It has now expanded into a nationwide — and worldwide — network.

Mariupol was built up during Soviet times as a large, industrial port, and Freefilmers’ identity is closely related to their city’s history. Their website states their interest in post-industrial landscapes and urban transformation. Mariupol became the site of a humanitarian crisis when the city was besieged by Russian forces for almost two months. Residents were cut off from water, electricity, heat, and food, and subjected to constant shelling. It is estimated now that 85% of the city has been destroyed.

In contrast to Babylon’13, Freefilmers are more explicitly political. Their mission statement explains their “current projects focus on memories and archives beyond official historical narratives and gender violence.” They are committed to “an anti-capitalist agenda and intersectional feminism.”

The group has 1,100 followers on Instagram and 142 on YouTube.

The videos range from purely observational to polemical. They produced a six-part mini-series documenting Ukrainian resistance with brave residents coming out to protest in occupied cities such as Berdiansk, Kupiansk and Melitopol.

One video features a 15-year-old girl’s video log documenting the siege of Mariupol. For a few seconds each day, she films her family melting snow into drinking and cooking water and struggling to stay warm in a city whose infrastructure is destroyed. From her window, she monitors the extent of the shelling. One night, the intensity of nearby blasts explode the apartment windows. She explains her family was unharmed because blankets protected them from the shards. She moved to safer ground within Mariupol and, finally, left the city.

Another, more polemical, video consists of a single seven-minute long take of Sashko, a filmmaker in Zaporizhzhia, playing ping-pong with local children. Over this idyllic scene, Sashko’ voice-over explains the Russian forces have just mined the atomic power plant there.

He chides Western viewers’ complacency. “I have just received a message from colleagues in the European Union, and they say they are already paying a huge price,” he explains. “This equates our lives to carbon, to fuel for their cars, for their industries, for their shitty economic growth.” Sashko’s soft voice grows more insistent: “You are simply not doing enough. Your shitty governments are not doing enough.”

Although Freefilmers’ archive of the war is smaller than Babylon’13, it adds critical viewpoints because the crowdsourced videos adopt a wide variety of forms, approaches, and arguments.

Freefilmers have also organized solidarity screenings of their documentaries produced before the war in Paris, Brussels, Helsinki, Kosice, Vilnius, and at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Toronto. As of April 2022, they have mounted sixteen screenings in nine countries. All were fundraisers. On their website, Freefilmers explain these funds specifically support aid for Ukranian “underground artists, queer activists, and neurodivergent people.”

Freefilmers also directly admonish Western filmmakers. In their mission statement, they proclaim: “we don’t need producers and directors from the Global North to come to Ukraine now and hire us as fixers for their revealing feature-length movies about the war … Help us to survive, and we will make our own films about what we have had to live through.”

WAW: War Against War

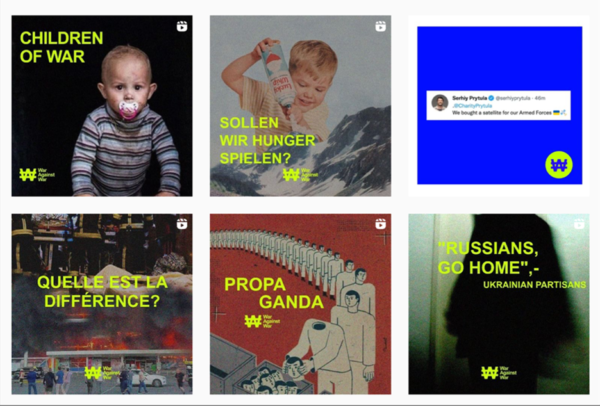

War Against War (WAW) is another important media group in Ukraine. Like Babylon’13 and Freefilmers, they work anonymously but with a different approach. The first two collectives document the war with observational or first-person videos that provide space for viewers to draw their own conclusions. In contrast, WAW counters the claims of Russian propaganda directly.

Formed by media professionals at the start of the invasion, WAW identify as a “creative front” and state their mission is to “guard the frontlines of the information war.” They have 17,000 Instagram followers though only 276 YouTube subscribers.

Their snappy short videos deploy irony and humor as they poke fun at Russian claims about Ukrainian Nazis. They employ shock editing, juxtaposing high production value ads for bread and pasta with images of grain fields on fire.

Unlike the Babylon’13 and Freefilmers collectives, WAW videos feature continuous voice-overs commenting on the images. WAW videos align more with Soviet-era agit-prop than documentary strategies of inquiry. Initially available only in English and Ukrainian, these videos have branched out into French and German.

War through Social Media

Documenting war and creating an archive of it isn’t new. What is new are their methods of storage and dissemination during the Russia-Ukraine War.

Prominent Ukrainian documentarian Oleksiy Radynski notes social media constitutes a defining feature of how we experience this war.

Babylon’13, Freefilmers, and WAW offer archives that expand in real time and can be accessed at any point. The platforms these groups use encourage non-linear viewing. Users can start with any video and then develop their own pathways.

These anonymous collectives challenge the dominant framing of social media as a tool for immersing in the latest news and unfolding developments and instead amplify its archival affordances.

Babylon’13, Freefilmers, and WAW revamp social media into something more lasting: an archival database collecting Ukrainian-produced media for post-war usage.

Masha Shpolberg is Assistant Professor of Film and Electronic Arts at Bard College. Her work explores global documentary, Russian and East European cinema, ecocinema, and women’s cinema. She is currently working on two edited volumes: “Cinema and the Environment in Eastern Europe” with Lukas Brasiskis, forthcoming from Berghahn Books and “Contemporary Russian Documentary” with Anastasia Kostina, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. She has written about the Babylon’13 collective covering the war for Docalogue (alongside Dale Hudson and Patricia Zimmerman) and “Film Quarterly’s” online column, Quorum. Masha is originally from Odessa, Ukraine.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (Indiana University Press, 2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (Indiana University Press, 2021).