Patricia R. Zimmermann opens her book “States of Emergency: Documentaries, Wars, Democracies” (2000) with a reality-check: “We are poised on a crumbling, frightening precipice as we edge into the enigmatic morphing media landscapes of the twenty-first century. Whether stationed in the academy or outside of it in nonprofit media sectors, we have been defunded and delegitimated. We urgently need a new world image order.”

She wrote during the first decade of public access to the internet and the end of the Cold War, when neoliberalists and techno-optimists dominated public discourse with the promise of globalization and digitalization to bring greater democracy and also economic mobility to all.

What unfolded over the past quarter-century has been much worse.

New York Police Department militarizes the Columbia University campus with an entire bus waiting to detain 108 students for protesting against complicity with the ongoing genocide in Gaza, Palestine. Images from World Socialist Review.

It isn’t simply the corporate bottom-line determining what news is reported or repressed. Social media accelerates the siloing of a public into echo chambers. Big Tech has perfected its design to render humans as monetized addicts. Public acceptance of mass surveillance of tech companies and governments has been normalized — and whistleblowing has been criminalized, as has migration.

Not only is independent media (by which she did not mean Hollywood’s “indie” films at Sundance) endangered, so too are universities, which she identified as the other potential space for open dialogue and debate. It is happening, not only in Florida, but also in the Ivies and the University of California system.

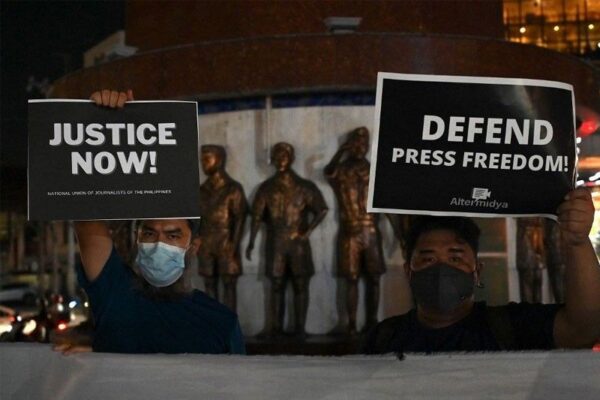

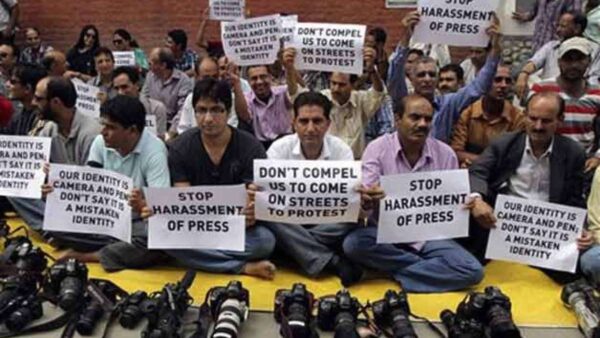

Demonstrators rally for justice following the murder of a radio broadcaster, who criticized government, in Quezon City, Manila, Philippines. Image from PhilStar Global.

Demonstrators against state violence against journalists in New Delhi, India. Photo from India TV.

Making everything worse, the problems are not contained to the United States but have been globalized. The “americanization” of news media has overtaken India and the Philippines, where news has been replaced by opinions and investigative journalists are being imprisoned, endangering democracy and also the maintenance of a livable planet.

Patty also outlines ways that a “counterpublic sphere of independent documentary and experimental media” might form. The Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF), which she co-directed, was envisioned as part of this sphere as was its longest-running online component, the new media exhibition.

*

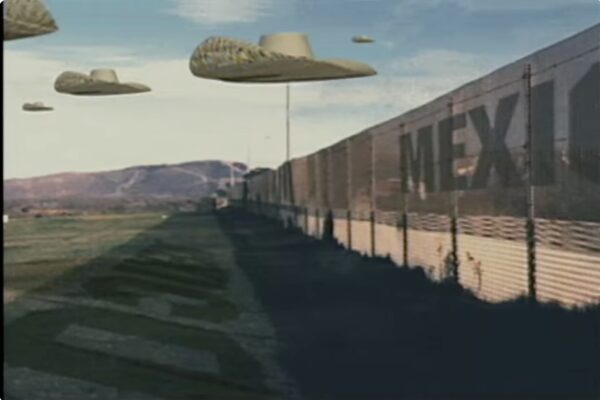

Discussed in “States of Emergency,” Alex Rivera’s “Día de la Independencia” (1997) counters U.S. nativism and racism (aka white nationalism) with an imagined scenario of sombreros hovering across the militarized U.S.-Mexico border to attack the White House with a red-hot chili-pepper laser. Screengrab from YouTube.

Sustained Turbulence for New Counterpublics

For the Sustained Turbulence exhibition at this year’s FLEFF, we decided to revisit work from past editions of the festival whose significance only seems to have increased.

The realization was hardly surprising since the festival was shaped by many of Patty’s ideas. She insisted that we act, make, think, and write with intentionality and with urgency.

For us, the continued relevance of her work and also the work curated for FLEFF evokes the sustained turbulence of the moment. Existential crises overlap and entwine in ways that can feel overwhelming, so historical perspective brings clarity.

During an online discussion with Armando Minjarez and Dorit Naaman at FLEFF 2024, we began to understand sustained turbulence also as a way of conceptualizing everyday practices of resistance or refusal of the dominant power systems that shape our sense of what is “normal.”

The sustained turbulence of our moment is defined by substantial uncertainties but also substantial urgencies. We invited the artists and filmmakers to reflect upon how the world has changed since they first made their work. In some cases, the world has changed profoundly; in other cases, it has not. In all cases, an urgency remains consistent, as does the need and desire for counterpublics.

CLIMATE: Because “extreme weather” now affects rich countries, it gets media coverage, yet it remains disassociated from global warming by decades of protectionist campaigns by fossil-fuel and other industries that naturalize it as “climate change.” Climate activism reaches beyond the weather into democracy.

ECOLOGY: Under global capitalism, shipping goods across the planet contributes to ecologically and socially destructive problems — and reveals our destructive over-consumption of planet’s finite resources. Thinking ecologically about the economy is also key to democracy.

MEDIA: Fake news is a juvenile-sounding colloquial expression for disinformation campaigns, which the United States and other states have used for decades to forward their interests around the world. Rebranded as fake news, disinformation increasing returns to the United States, potentially affecting democratic elections.

WAR: The ongoing deadly wars in Palestine, Sudan, and Ukraine raises different issues about the role of the United Nations (U.N.) and other international organizations, which reopen unsettled histories from the past, notably with the U.S.-backed Israeli attacks on U.N. aid, crisis, and medical staff.

We offer the exhibition and these reflections by some of the participating artists and filmmakers as way to cut through the political theater that dominates cable news cycles since it generates healthy financial revenue for billionaires and corporations.

From our perspectives as curators, we notice that the projects and reflections speak to increasing political polarization and insularity, unaddressed global warming, embattled media, and urgent immigrant and refugee situations — all regressions from when we started, a decade ago.

We hope that these reflections by artists participating in our first exhibition at FLEFF without Patty might encourage all of to us act and think with urgency and intentionality, as she taught both of us to do.

To be continued … and with sustained turbulence against what is unfolding as “the new normal” of unending states of emergency!

*

One iteration of predicting the future by noticing the weather in Amelia Marzec’s “Weather Center for the Apocalypse.”

CLIMATE

Much like rightwing pundit Frank Luntz coined the term “climate change” to discredit climate science and promote the business-as-usual policies of extracting coal, natural gas, and petroleum, which release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when burned as fuel, so too does the term “extreme weather” obscure important details.

Global warming amplifies and accelerates naturally occurring weather phenomena. The regularity with which draughts, fires, floods, mudslides, and storms occurs is what climate scientists have been warning us about for decades.

Amelia Marzec’s “Weather Center for the Apocalypse” (2015–2017) is a community media project that alerts us to the importance of thinking beyond ourselves. Nearly a decade later, its significance has only increased. As she points out, reading the weather and understanding our climate are urgent matters the more as the COVID-19 pandemic showed that slowing down anthropogenic impact had a positive effect on our Earth’s systems.

Amelia Marzec Reflects on “Weather Center for the Apocalypse”

“Weather Center for the Apocalypse” is a project that creates forecasts combining information from the internet, the local microclimate, and word-of-mouth predictions and fears from participants. The predictions are collected over the course of a day, inside of an installation that is a physical room filled with homemade weather instruments, and equipment for broadcasting. At the end of the day, the forecast is complete — with an alert predicting whether the situation is dire for that day, and what human activity occurred that could cause the world to end.

I ran this project for nearly three years prior to the pandemic. During the pandemic, I had moved on to other work, but several people suggested I make more forecasts. However, I declined to create any at that time, as the wry humor of the project wasn’t going to land well in New York City, where I was living and which was hit very hard in the first wave of the virus. For us, it was too real. I also realized that the Weather Center hadn’t even predicted a pandemic!

As things were slowly going back to normal, I began feeling drawn towards the project again. During the pandemic, the air became clear temporarily as less cars were on the road. People had time to slow down and prepare home-cooked meals. There was progress in social justice movements. There were silver linings that began to dissipate as things went back to “normal.” Suddenly, the cost of food and housing increased. Concerns about climate change returned as production increased. Wars broke out. Was this what we considered normal? How will we respond to this seemingly exponential pace of capitalism?

*

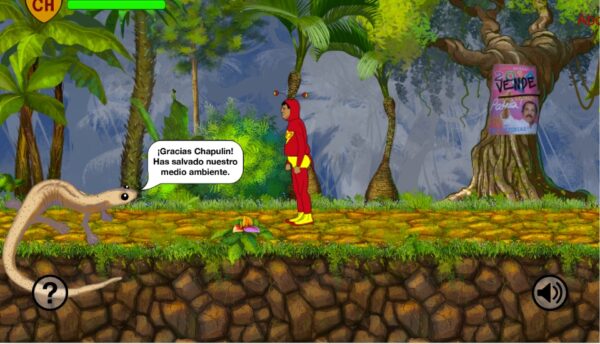

Screengrab of gameplay in Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga’s “Ometepe.” Game available on artist website.

ECOLOGY

Ecology emphasizes interconnections. Ecosystems are ways of living together through interconnections and interdependencies. No one understands this better than Indigenous and enslaved peoples, who have often been subjected to violent histories of dispossession and genocide for access to their land for its so-called natural resources.

This process has only accelerated since the 1990s. Under global capitalism, cheap goods are shipped around the world in container ships through chokepoints in the supply chains like the Panama and Suez canals, which were made by humans at considerable damage to local ecology. Cheap goods at our local superstore or favorite online vendor can come at a cost of harming both fragile ecological and political systems.

Reflecting upon his video game “Ometepe” (2016) about an island in Nicaragua whose existence was threatened by the combination of a global financier and local authoritarian politicians, Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga describes how the political situation in Nicaragua has become much worse since he made “Ometepe,” and yet the island of Ometepe itself remains relatively safe from the canal project, though there remains no reason to imagine that the threat is gone.

Miranda teaches us how to think beyond our immediate gratification, even on environmental issues, since the struggle must always continue.

Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga Reflects on “Ometepe”

In April 2018, former-billionaire Wang Jing, who agreed to build a canal across Nicaragua to rival the Panama Canal, abandoned his office in Hong Kong, leaving no forwarding address or telephone numbers to be reached.

Also that month, Rosario Murillo, the “Vice President of Nicaragua” and wife of dictator Daniel Ortega, announced social security reforms that would increase taxes and cut benefits. Nicaraguans immediately took to the streets to protest these social security reforms. Police and paramilitary groups attacked and killed unarmed protestors.

In a small country with a population of under seven million, hundreds were murdered in five days of protest. The Ortega dictatorship rescinded the social security reforms, but murder against innocent people had already been committed. The protests continued, more protestors were murdered and hundreds were imprisoned.

The year 2021 saw a national election in Nicaragua, but the Ortega-Murillo regime detained the opposition candidates. In December 2020, a law was passed to facilitate the imprisonment of any opposition on the basis of possibly stirring social unrest. Law 1055 ultimately makes any opposition to the ruling party a terrorist act.

Leading up to the elections, the police arrested opposition candidates and high-profile activists using Law 1055 as a pretense for detainment. The government expelled independent election observers. Following Ortega’s fourth re-election, in 2022 the government closed over 2,000 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Today, Nicaragua remains an authoritarian state under the Ortega-Murillo regime. There are no more protests. Any critique of the dictatorship is whispered amongst trusted individuals because one never knows who is listening. Fortunately, the Nicaraguan Canal will not be realized and Ometepe remains a nature reserve.

*

“21 in Libya (February 2015)” from Brandon Bauer’s “Landscapes of Absence” that removes the violence in Daesh (ISIS) recruitment propaganda.

MEDIA

The term fake news is sometimes difficult to read without hearing the tortured pronunciations of former U.S. president Donald Trump, who uses the term to discredit information and promote disinformation. However, disinformation has been used as a military and political weapon by the United States and other powerful countries for more than a century. With the end of the Cold War, new non-state entities began producing their own propaganda.

Brandon Bauer reflects on “Landscapes of Absence” (2015), which examined how Daesh (Islamic State aka IS, ISIS, or ISIL) pioneered the use of social media to spread disinformation and recruit followers. Through its media production wing, Daesh produced high-end media in a dozen languages. Its use of social media to spread images of attacks and executions shocked the world. As much as Daesh used social media, particularly Twitter (now known as X), scholars find that it was also shaped by it.

Bauer makes a case for the need of improving our media literacy — and not rely on profit-driven social media companies to protect us from disinformation and misinformation.

Brandon Bauer Reflects on “Landscape of Absence”

Created in 2015 and first exhibited in 2016, “Landscapes of Absence” is even more resonant today than when it was first created.

This has been amazing to see, especially given that this project was nearly abandoned as it was being developed. The news of the emergence of ISIS moved so fast that I almost deserted this project several times, thinking the nuance I was attempting to bring to the project would be lost in the fog of the spectacle.

The project explores ethical issues around the use of ISIS propaganda within broadcast media in the absence of reliable and journalistically objective images. In the project, I used images drawn from eight beheading incidents disseminated through ISIS media outlets that were widely redistributed as b-roll footage by established broadcast news media.

In this project, I erased the dehumanized image of the victims and their captors, leaving only the landscape and the absence of the image as a metaphor for the more significant issue of the absence of reliable reporting from areas under ISIS control.

ISIS were expert manipulators of social media ecosystems to amplify their message far beyond their base of support. They pioneered and amplified viral techniques, like the use of social media bots and hashtag hijacking, to spread their high-production images and videos through sophisticated branding strategies one would associate with commercial productions.

In many ways, ISIS opened the floodgates to the post-truth era. Their campaign made broadcast media accomplices as their propaganda replayed on the nightly news when journalistically objective images from the area under ISIS occupation were unable to be obtained.

“Landscapes of Absence” has continued to be exhibited in whole or in part since the first exhibition of the work. As curator Helen del Guidice stated on the occasion of the work’s exhibition at the Miller Art Museum in 2022, “the exhibit, while specific to incidents of terrorist violence and propaganda, easily extends into other ethical issues surrounding journalism at a time when similar tactics are being used in current war zones and when press are under a great deal of scrutiny.”

The tactics ISIS developed have only been further expanded by numerous actors using the “firehose of falshood” propaganda model, from Russian troll farms and alt-right meme warriors engaging in election interference campaigns to influencers, celebrities, and businesses buying social media likes, followers, and viewers from offshore “click farms,” where low-wage workers tap away at the like button through sockpuppet accounts to inflate social media numbers. As AI-generated content and the development of deepfakes become easier to create and spread, the need to question what we see, hear, and read will only become more important.

With “Landscapes of Absence,” I made the case that artists have an ethical responsibility to consider deeply the images we consume and the images we create. Now more than ever we need to be critical of the narratives we are fed through algorithms, and we need to work to disrupt propaganda cycles with assertions of humanity, dignity, and truth.

*

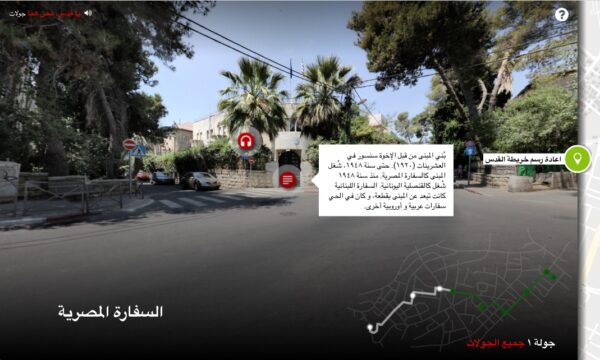

Screengrab of interface in Arabic-text option in Dorit Naaman reflects on “Jerusalem, We Are Here” on a tour of Qatamon neighborhood in Jerusalem. Image from project website.

WAR

The ongoing Russian war on Ukraine, civil war in Sudan, and Israeli war on Palestine have contributed to greater numbers of civilian deaths, including ones of civilians who have fled war. In addition to violations of international law and human rights and untold ecological damage, these wars are violent exercises in the worst kinds of nationalism.

Dorit Naaman describes how much further we have strayed from the pre-Israel Jerusalem that she works with others to recover in “Jerusalem, We Are Here” (2016). The interactive documentary includes a mapping component that allows users to visualize the city’s layered human history, suggesting erasures of its cosmopolitan past under multiple empires, including the British. The Gaza Strip is already a home to refugees of the 1948 Nakba (catastrophe), as Jewish Zionists, who themselves were mostly refugees from the European nationalism, razed Palestinian villages, massacred civilians, and annexed land.

For many Israeli activists, historians, and intellectuals, countering Nakba denial is a necessary first step in ending violence. It is a brave one that requires recognizing oneself, both as victims of European anti-Jewish racism, and also as victimizers with Israeli anti-Arab, particularly anti-Muslim-Arab, racism. The recent Hamas military murder and kidnapping of Israeli civilians represent a setback to this necessary work by Jewish Israelis. Work like “Jerusalem, We Are Here” helps reset the historical clock, not only to a moment before 2023, but also before 1948.

Naaman shows that we need to engage historical perspectives as evidence that war cannot be resolved when supporting exclusionary nationalisms.

Dorit Naaman Reflects on “Jerusalem, We Are Here”

In the immediate aftermath of the Hamas massacre on October 7, 2023, the trauma of the Holocaust was palpable for all Israelis (and many world Jews), making many unable to see beyond October 7.

At the same time, Israeli retaliation (still ongoing) has resulted in 40,000 Palestinian deaths (and counting), and the destruction of 70% homes in Gaza, thus making almost 2 million Palestinians refugees, reignited the trauma of the 1948 Nakba for all Palestinians.

In this moment of horror, death and so much trauma, it was difficult to see how “Jerusalem, We Are Here” — a 2016 interactive documentary that digitally brings back to their Jerusalem homes Palestinians expelled during the 1948 war — is relevant, if at all.

But as time passed, I started thinking of some lessons I learned from “Jerusalem, We Are Here” that are quite relevant now.

Jerusalem of the 1940s was a cosmopolitan place, and almost everyone in the affluent neighborhoods of southern Jerusalem spoke multiple languages. Jews and Arabs studied together, co-owned businesses, and even inter-married. Religious and ethnic affiliation was important, but the society was not segregated.

The post-October 7 common narrative is that Israelis and Palestinians cannot live together. The messianic (both Jews and Muslims) dream of an ethnically pure space someday; the fascists and ultra-nationalists talk about expelling the “other” group now, and the international left has a utopian decolonial vision that negates the national aspirations of both Palestinians and Israelis.

Within this binaristic and exclusionary discourse, it is very important to remember that we once all lived together, and that perhaps we need to look to the past, in order to have a future.

In his memoir “Day of the Long Night: A Palestinian Refugee Remembers the Nakba,” Jamil Toubbeh, the son of the Greek Orthodox mukhtar (leader) in Jerusalem, and a valued contributor to “Jerusalem, We Are Here,” recounts having a Jewish-Polish girlfriend. The girlfriend was a refugee of Nazism, but not a Zionist, so neither him, nor his esteemed family saw a problem with the relationship.

When we met in person in 2017 to co-present “Jerusalem, We Are Here” at the Jerusalem Fund in Washington, D.C. Jamil recounted the story with a twinkle in his eye. We then talked about the complex role of Zionism in both providing a refuge to Jews escaping extermination, and at the same time as a force of displacement and catastrophe for Palestinians.

It is these nuanced conversations that are so sorely missing from the discourse right now, and which I hope, “Jerusalem, We Are Here” can still engender.

Header image of Patty Zimmermann on the frontlines of a strike at University of Wisconsin Madison as a grad student. Photo from Facebook.