The Pandemic is Not Over

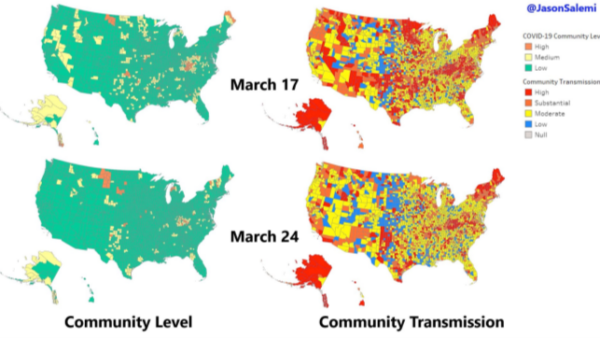

Four days before the 2022 State of the Union address, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (the CDC) made a change to the risk-prevention pandemic map of the United States that changed the color of the map from red to green.

Before the change, the CDC worked with guidelines that identified a substantially high risk as 50 cases per 100,000 people. After the change, the low-risk category became 200 cases per 100,000, a significant diminution of the original calculations.

The People’s CDC (called the PCDC) issued a response along with a link to a map that illustrated the change:

“The resulting shift from a red map to a green one reflected no real reduction in transmission risk. It was a resort to rhetoric: an effort to craft a success story that would explain away hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths and the continued threat the virus poses.”

The PCDC is a collaborative of volunteer health experts who craft and offer policy recommendations and guidance around COVID-19 issues. Their work reframes official U.S. responses to the global health crisis by disseminating critical information across a variety of social media platforms.

PCDC is built on a foundation of restorative justice, world building, and collective action. As they note on their website: “working alongside community organizations, we are building collective power and centering equity as we work together to end the pandemic.”

PCDC resists the hegemonic inequities embedded in state-run public health systems and corporate mass media by rewriting the rhetorical strategies of those systems. The PCDC’s restorative, collective ethos responds to global crisis by building racial counterpublics through a liberatory social justice collaborative.

What is at Stake?

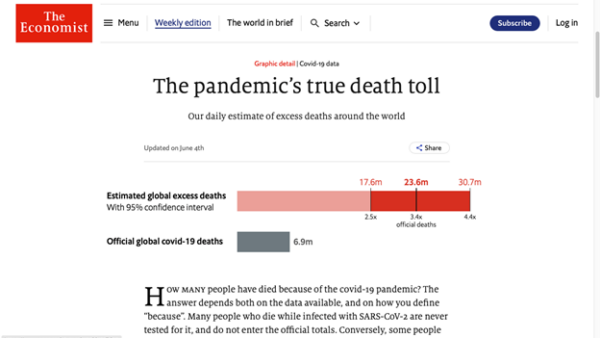

On June 16, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 767,984,989 cumulative official cases of COVID-19 and 6,943,390 official deaths. Conservative estimates of total global excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, suggest that the number of covid deaths is closer to 20-30 million.

Someone is dying of COVID-19 every four seconds.

Globally and in the United States, COVID-19 is an ongoing crisis, particularly for historically exploited populations. The number of people suffering from long Covid is estimated to be 1 in 5 of those who have been infected. The number of people whose lives have been forever altered by the loss of family and/or community members is incalculable.

However, both the WHO and the CDC are deescalating their COVID-19 programs.

On May 5, the WHO advised that “the COVID-19 pandemic … no longer constitutes a public health emergency of international concern.” The CDC declared the end of the public health emergency on May 11.

The consequences:

- COVID-19 tests are no longer covered by insurance

- national and local reporting on COVID-19 cases and deaths has almost entirely stopped

- access to federal food assistance programs that were enacted during the pandemic is gone

- around 15 million people will soon lose state Medicaid coverage.

The PCDC was formed in response to the United States’ inadequate COVID-19 policies. It continues to push back against movements like the decision to end the pandemic state of emergency.

Scholars of collective action in U.S. health care identify four sentinel reasons for the growth of health-related social movements in the U.S.:

- gatekeeping by specialists

- classification of patients by disease

- gender imbalances among medical professionals

- and the corporatization of healthcare.

When you become ill in America, you become subject to a system built for profit and efficiency, not patient care. The system aggravates already present cultural inequalities around race, gender, and class. The PCDC’s collective ethos pushes back against these problems by performing what Ruha Benjamin, author of “Viral Justice” (2022), calls “abolitionist world-making.”

Collective Action

The PCDC began in a listserv discussion about an article on Medium, which grew into an online forum and mushroomed into a collective all within about a week in January 2022.

In the PCDC Introductory Webinar, Dr. Mindy Fullilove uses the language of collective action and restorative justice to describe the PCDC’s origin story and their commitment to collective, social-justice oriented public health information sharing.

The webinar explicates the multi-modal deployment of interactive digital tools for creating a public health counterpublic central to the PCDC’s work. Dr. Fullilove’s invokes Shirley Chisolm’s motto “Unbought and Unbossed” while foregrounding the intolerable condition of information sharing at the Federal level during the pandemic.

The PCDC strategically align themselves with the U.S.’s long history of community and cultural intervention into mainstream political discourse and power.

For example, the newspapers of the 1960’s feminist movement buoyed national activism against employment discrimination based on gender. The theatrical storytelling of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) steered movement among both drug companies and the national government on AIDS research in the late 1980s and 1990s.

As many scholars have noted, community-centered framing can shift healthcare policy and practice.

Built on democratic, collective labor, the PCDC offers an alternative public health structure that both resists the US Federal response to COVID-19 and provides direct resources to the public via their publications.

The PCDC uses a layered and collective approach to information sharing. The PCDC follows the model that Jackson, Bailey, and Foucault Welles identify in “#Hashtag Activism” (2020) when they locate efforts toward “solidarity and community building” in contemporary counterpublics use of available media technologies.

The organization’s about page provides an example of collective world-making in the abolitionist spirit. It includes a map of their collaborative, team-driven workflow. It chronicles their members who are public health researchers with arts expertise, poets, community activists, primary care physicians, evolutionary epidemiologists, data scientists, biostatisticians and more.

The fixed banner on all pages offers links to the variety of social media platforms across which the PCDC shares their messaging such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok. As well as their blog, it offers a place to click to join the mailing list, distributed via Substack.

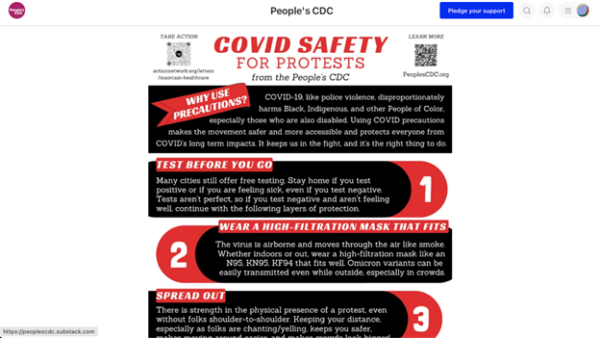

The PCDC remixes and remediates the infographic styles of CDC and WHO reportage in order to share critical information across media platforms. They mobilize the interactive social media tools which typically represent the U.S. mediasphere’s neoliberal gig economy. In contrast, they use those tools to publish and share critical public health resources.

The layered, collective, and equitable information sharing labor of the PCDC constitutes productive resistance to the typical failures and mobilization of the U.S. response to the ongoing pandemic.

Mutual Aid

Ruha Benjamin sees mutual aid as an “on-ramp for people to get involved in social movements.” Benjamin invokes Seattle-based organizer Dean Spade’s definition of the ways that mutual aid organizations materialize three types of movement work:

- dismantling harmful systems

- providing for people’s immediate needs

- creating alternative structures that can meet those needs based on values of care, democratic participation, and solidarity.

The PDCD’s Weather Reports do all these things. These reports represent an ongoing post distributed across platforms. They act as a clearinghouse for updated data about transmission, variants, wastewater monitoring, masking, hospitalizations, and deaths.

The Weather Report constitutes part of the PCDC’s ongoing project to appropriate mass media messaging through recontextualization and redistribution of data.

The Weather Report features a forecast and links for taking action.

For example, a recent report invites readers to join in support of a National Week of Action to Keep Masks in Healthcare because the “widespread dropping of universal masking in healthcare is just the latest example of institutions following the politics rather than protecting people using science-based methods.”

Another recent report includes an infographic of COVID-10 wastewater levels, discusses recent studies of long COVID, and makes space for public comments in support of widespread booster availability.

The Weather Reports invoke the public health concept of “weathering” coined by Arline Geronimus to describe the ways that people are forced to “weather” the challenges of living in our environment. She points out how “weathering” stress leads to preventable illness and premature death.

The PCDC website also offers exhaustive resources for information-starved publics.

Although many online resources talk about what to do when you contract COVID-19, few provide such a detailed list with items such as the PDCD’s “What to Do if You Have COVID” and “Preparing for Illness.”

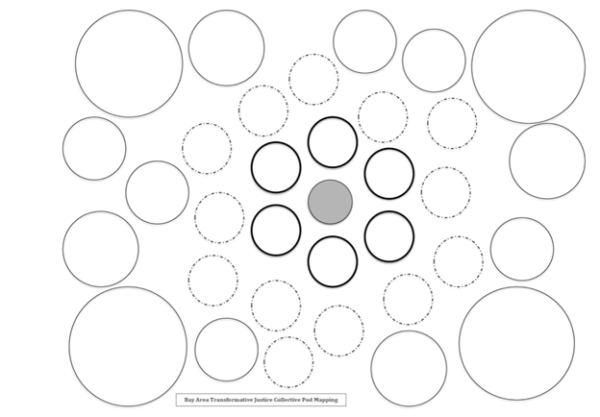

The guide to “preparing for illness, preventing spread to others, managing symptoms, and recovery” emphasizes layers of protection, planning ahead, educating others, and social support. They offer, for example, a link to a “pod mapping” exercise from the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, which helps people to identify people and communities that they can tap into for mutual aid and support.

I have spent weeks and months scouring the internet for COVID-19 information, but I have not seen a single other resource that frames illness preparation as an opportunity for community engagement and an acknowledgement of communities of care.

Interdependence

James Baldwin said “We are living in a world in which everybody and everything is interdependent.” COVID-19 exposed an incontrovertibly material example of this interdependence.

The PCDC embodies a discursive and activist strategy to build a world for public health with more interdependencies.

As the PCDC says in a recent Weather Report, “We would like to remind you that you are not alone. We are stronger together. … Let’s continue to band together and fight to win the protections we all deserve.”

These processes, use of multiple kinds of platforms, and new kinds of analysis present the possibility of restorative justice for health care in the midst of the continuing, shape-shifting pandemic.

Leah Shafer is Associate Professor of Media and Society at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. She recently published a co-written essay on early US pharmaceutical advertising and medicalized consumers in the Routledge Handbook of Health and Media. She is an Associate Producer and Programmer for the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival.

Header image by Jakayla Toney on Unsplash.