In 2019, the Massachusetts Attorney General sued Exxon Mobil for deceiving state residents about the company’s contributions to climate change. One of the lawsuit’s exhibits featured a New York Times-published piece of “native advertising,” paid content disguised as a news article, in which the oil company discussed “The Future of Energy.”

“So this is concerning,” Dr. Michelle A. Amazeen said. “What is Exxon Mobil saying in their native advertisements? Does it contradict what The New York Times newsroom is saying?”

During a recent talk hosted by the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, Dr. Michelle A. Amazeen shared her research that demonstrated how poor enforcement and standardization of native advertising damages journalistic integrity and muddles real reporting.

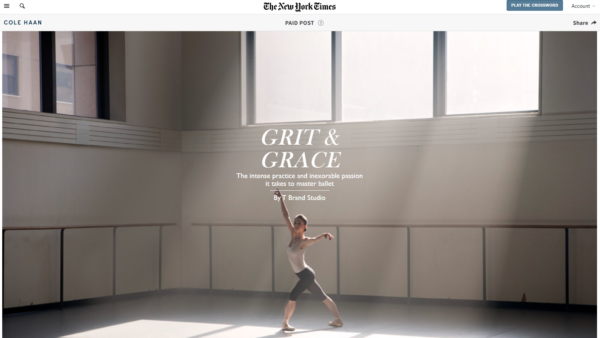

Native ad campaigns can be relatively innocuous, such as a story on The New York Times’ website labeled as a paid post from a fashion brand.

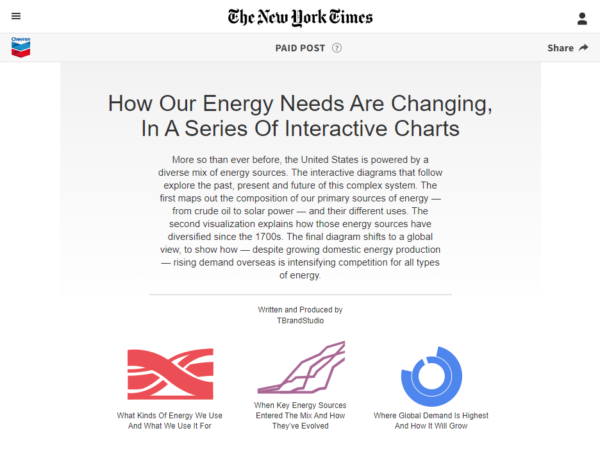

“But it’s not just fashion brands engaging with news outlets to do this,” Amazeen said. It’s also tobacco companies and the fossil fuel industry. The New York Times’ in-house ad agency, T Brand Studio, also ran a story entitled “How Our Energy Needs Are Changing, In A Series Of Interactive Charts,” with a disclaimer labeling it a “PAID POST” by oil company Chevron.

“So people are seeing this content about global energy consumption that seems to be an article in the New York Times, only it is paid content by Chevron,” Amazeen said. “You can imagine that there may be some bias in the content because of its sponsored nature.”

Amazeen defined native advertising as “a type of covert marketing practice where an ad mimics — or appears ‘native’ to — the platform on which it appears.” In print news, preceding this strategy was the “advertorial,” an article that looked like an editorial, but was paid for by a sponsor.

Digital native advertising was developed when print ad revenue fell off in the early 2000s, as internet news gained prominence and as people employed ad-blockers to avoid interruptions. “Presumably for consumers,” Amazeen said, “it is less disruptive because you don’t realize you’re reading an ad.”

Native advertisements are required by the Federal Trade Commission to be disclosed from news and entertainment content. The FTC reaffirmed this law in 2015 to remind advertisers and publishers, but no standardization exists to determine what those disclosures must say. As a result, Amazeen’s research has shown that only 10–25% of people tend to catch these warnings.

Research in Mara Einstein’s book “Black Ops Advertising” lists several strategies outlets use to obscure their disclosures, such as lightened and shrunk font.

Disclosures are even harder to recognize on the small screens of mobile devices. And Amazeen’s research alongside Chris Vargo of University of Colorado exhibited how they disappear entirely more than half of the time when readers share articles on social media.

In a nationally representative survey from another of her experimental studies, Amazeen illustrated that the more prominent the disclosure — such as when it was surrounded by a brightly colored box — the more people were able to recognize native advertising. This test similarly indicated that the presence of a logo made commercial content noticeable, as did explicit language: the phrase “advertisement by,” followed by a named sponsor, was clearer than merely “partner content.”

Native ads also deter news outlets from covering topics they’ve been paid to promote. Amazeen’s study with Vargo determined that “Half the time after a fortune 500 company ran a native advertisement, there was significantly less news coverage of them in that outlet. So this is an agenda-cutting effect that we found.”

Amazeen’s research lays bare an imperative for the media ecosystem to reinvent a revenue process that shreds journalistic integrity, contradicts genuine news, and suppresses future reporting. Standardized disclosures, including with digitally embedded disclosure watermarks, would help readers recognize native advertising.

The FTC’s existing regulations should ensure ad disclosures are explicit, but they remain ineffective without stricter enforcement. Amazeen encouraged news publishers to self-supervise by reassessing the risks and benefits of harming long-term reputation to generate immediate revenue.

Readers must employ critical media literacy skills to recognize trusted information sources while confusing content gets in the way, because as Amazeen said, “we have a finite amount of time. If we’re being served native ads, we’re not paying attention to the real news.”

Dr. Michelle A. Amazeen is the Director of the Communication Research Center and an associate professor in the Department of Mass Communication, Advertising and Public Relations at Boston University. She noted the research shared in this talk, entitled “Content Confusion: Navigating the Media in an Era of Misinformation,” is making its way into a book of the same working title.

Image by Julian Hochgesang on Unsplash.