Augmentation is not defined exclusively by emerging digital media forms, software, and interfaces.

Instead, augmentation explores how to generate new processes about how to think through, with, and within place that spans the digital, the analog, and the embodied. Not all augmented documentary forms utilize new technologies.

The shorts and feature length films of Yi Cui augment place by inscribing a stationary camera with long takes that explore duration, temporality, space, and politics.

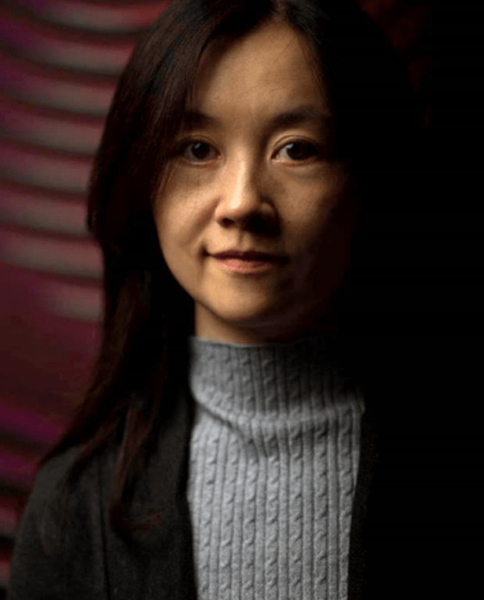

Yi Cui is a Chinese filmmaker who trained at York University in Canada for her MFA. She currently teaches filmmaking at Colgate University in upstate New York. Her other degrees are in ecology, a way of thinking that infuses all her work. Her films use carefully placed cameras to create environments for the spectator to inhabit rather than to simply watch from outside.

Her films include “Ying” (2011), “Of Shadows” (2016), “Qiu (Late Summer)” (2017), “Through the Looking Glass” (2017), and “Screening from Within” (2018). Her filmmaking navigates a liminal zone between ethnography, painting, ecologies, cinematic histories, and self-reflexive cinema. She has worked extensively with community media producers in Tibet on autoethnographic filmmaking projects in an initiative entitled “From Our Eyes,” a participatory community media project that counters outside Western and Han Chinese portrayals of Tibetans.

Yi Cui, filmmaker

Cui considers her work an “open process” to encounter what she calls “time-space.” She explains, “I make it a principle to not impose the time-space of a preconceived structure on what surrounds me on the ground. Instead, I first immerse myself in a place and the rhythms of local life.”

Her cinematographic approach differs from an older generation of Chinese radical independent films such as “Bitter Money” (Wang Bing, 2016), “China Concerto” (Bo Wang, 2012), “Meishi Street” (Ou Ning, 2006), “Street Life” (Zhao Dayong, 2006), “Til Madness Do Us Part” (Wang Bing 2013), “Anni” (Rkun Zhu, 2018), and “No Desire to Hide” (Rikun Zhu 2021). These filmmakers use small digital cameras to interrogate the disruptions between the state and everyday life in urban areas in a mode-evoking direct cinema. The films expose confrontations, disturbances, and disjunctures between the state and citizens in very compelling, micro ways.

Cui’s films adopt an aesthetic that is 180 degrees different from these filmmakers. Her films do not employ the direct cinema handheld strategies of these works, nor do they provoke confrontations.

Instead, in a counter move to this older generation of filmmakers, her works reference practices of the recent global movement of slow cinema. An aesthetic of long shots and almost no interest in individual characters or narrative inflects this form of cinema. Slow cinema eschews fast editing and action, emphasizing immersion in space and sound through multiple temporalities that can feel meditative.

Cui ruminates, “I am fascinated by mise-en-scène in Cinema. I was deeply influenced by filmmakers like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang, Antonioni, Weerasethakul, who are all masters of mise-en-scène. Although in non-fiction work, you cannot ‘direct’ people and objects in order to foster a dynamic scene, I find it equally interesting to capture evolving relationships and movements among all components in frame.”

“I usually take some time to understand the space where I’m situated and all the elements in it — it is my ‘rehearsal.’ Then I can prepare the camera angle with some confidence in where things may go, while leaving the rest to spontaneity. Sometimes, it takes a very long time for the scene I anticipate to happen, sometimes it never happens. I’m not the ‘director,’ time is the invisible director, and I’m her patient collaborator.”

With their long takes, long shots, and careful stationary compositions, Cui’s films unfold mise-en-abymes of nature, people, and technologies. These structures embody the cinematic process of augmentation where place becomes more important than characters or drama.

“As for the distance, I do not think it was a conscious choice. Many years of living between places and cultures of Asia and North America have detached me from the centers of many things. I often feel I’m situated on the margins observing the center. I suspect this must have influenced my framing choices,” Cui reflects.

“In retrospect, I think my filming approach is subconsciously influenced by Chinese paintings, which I love, and which often portray humans as small elements in the landscape and the space.”

“Through the Looking Glass” (2017) is a 14-minute film shot in the highland pastures of Tibet in Golak. It emphasizes place and sound rather than individuals and stories. The film opens with a long shot executed in a long take of some Tibetan herdsmen sitting on the shore on the edge of a lake. The camera’s only movement comes from the high winds, suggesting that the camera is part of the environment and impacted by the weather.

“In ‘Looking Glass,’ my camera was responding to the rhythm of the summer pasture — yaks by the lake, smell of the grass, wind blowing, riders and their horses taking a stroll — none of them was rushing, why wouldn’t I listen to them?” Cui elaborates.

The soundscape of this film intensifies our experience of place as we hear wind, water, engines, animal hooves, laughter, barking dogs, and rain. The untranslated conversations do not take priority, positioned instead as merely another layer of human sound in nature.

Elaborating why she does not translate the minimal dialogue, Cui says “I wanted to use an audiovisual language to bring the viewers into an embracing space to feel and to observe. To understand the community in the film, we can certainly decipher through subtitles translated from Tibetan language, but I believe we can already learn a lot through people’s expressions, gestures, how they move, how they work, how they play, how they gather, etc. When we free our attention from text, we can see a lot more in all of these.”

Herdsmen and women, horses, cars, motorcycles and children move in and out the frame, the open framing technique underlining how even with a static camera there is still movement and dynamism between the human and animal world. A group of herdspeople put up a large white tent. A long shot of the tent shows it dwarfed by the landscape of the pasture and the mountains.

The film produces a mise-en abyme about cameras, cinema, and nature. In one shot, a group of men lay on the ground with a camera in the middle. In other shot, a monk uses another monk’s shoulder as a tripod to shoot directly at the filmmaker. A man walks down a hill carrying a camera on a tripod. A long shot shows the white tent lit up at night. The tent is not foregrounded but integrated as an element of the landscape and the tableau shot. The only close-ups in the film follow with images of children, women, and men looking at something. A dog barks. An older man spins a prayer wheel.

In a reversal of films-about-films, “Through the Looking Glass” shows the sequence of the spectators in the tent first, and then reveals they are looking at community produced films in a community-organized festival.

The imbedding of cinema into daily life is critical in Cui’s cinema. She notes that “Now watching the film again, I feel the tent on the pasture is almost a metaphor of a cinema that is inseparable from life — a cinema not simply functions as a mirror, but also as a transmitter that directly transforms community life. Indeed, many grassroots Tibetan films have been serving this role.”

The films are projected on the cloth walls of the white tent, the images oscillating like the waves on the lake in the opening sequence as the cloth billows and moves in the wind. The images show young children sledding down a hill. The imperfections of the images and their projection suggests that they are not stable but always changing and responsive to the environments in which they are projected.

The final shot of the film is a young girl dressed in pink on a green field. As she walks, the camera follows her, some of the only camera movement in the film. As Cui notes in an interview on the dGenerate Films website, the process of working in Tibet “taught me … to see human beings or to see ourselves only as a small part of a larger ecosystem.”

“Qui (Late Summer)” is Cui’s 13-minue 2017 documentary. It explores a century-old Beijing theater that has transitioned into a transient space for tourists to watch traditional Chinese juggling, acrobatics, and singing. Resonating with “Through the Looking Glass,” the film positions cameras and performance as secondary to the elaboration of place augmented through a layered soundtrack.

Cui discusses her choice of place as an act of historical staging: “In Late Summer, the theatre space itself is a character. It’s been standing there for so many years, through the old dynasty, through the revolution, and now through what’s happening in contemporary China. Both history and reality have been staged and re-staged, like those tourists and performers, passing by, whereas the space is there witnessing all, and carrying its own memory.

The film consists of one extended 13-minute stationary symmetrical long shot with the camera in the back of the theater at eye-level, suggesting that the filmmaker is standing. Tables filled with tourists occupy the foreground. The background of the shot features a red fabric background decorating the stage, set in the middle of the frame. The stillness of the camera produces a cinematic canvas to augment. Camera movement and editing are excised, and instead, this long take signals that the act of filmmaking and framing produces not stories but place, with the spectator inserted as an observer of both audience and performance. Banks of windows covered with yellow and blue filters flank the composition, blocking direct sunlight and suggesting a completely manufactured environment without natural light.

Yi Cui explains her process: “In “Late Summer,” my instinct asked me to let the camera patiently wait, until it discovered the cycles of people passing through the space. The transient and rapid cycles staged in the theatre and the theatre space itself have completely different rhythms. Only showing it continuously and in its real time can portray this deeply haunting tension.”

The film is structured to minimize the performance as spectacle or as dominant in the composition. The first half of the film features theater workers setting the tables with cups and bowls, moving in and out of the space and the frame.

Tourists flood into the frame from the sides and from behind the camera, rushing to secure tables. Cameras hang from their necks and many take pictures of the stage with their cell phones. This gesture suggests another kind of mise-en-abyme of self-reflexive image-making with the filmmaker’s carefully composed long shot, the tourists cell phones, and the performers on the stage.

Three dancers, a young boy acrobat doing handstands, women singers, and two women jugglers perform to pre-recorded music. The audience films them. The singing and the music are distant, not foregrounded.

Similar to “Through the Looking Glass,” the singing and the conversations are not translated. Instead, they offer an immersive soundscape where the immediacy of the sounds and texture of language matter more than denotative conversations dislodging documentary from logos and moving it towards a slow immersion in image and sound.

Yi Cui’s films constitute a significant intervention into Chinese independent and diasporan cinema. They foreground how cinema creates space through compositions that open up to movement and the layering of sounds. They expand concepts of augmentation beyond the digital into the analog, but stage the analog as a space rather than as a story. “Through the Looking Glass” and “Qiu (Late Summer)” unfold two strategies of augmentation.

First, they employ slow, long takes in long shot to indicate a different sense of time. Layers of natural, human, and machine-produced sound shift and intersect. These stationary long shots dislodge the privileging of characters, narrative arcs, and speech to augment an aural immersion in soundscapes.

Second, as films that create mise-en-abymes about cinema, Cui’s films imbed the image into the environment, place, and people, all of which occupy more screen space that the cameras or projected images.

Cui views her filmmaking process as a collaboration: “I do believe both filming and editing is a dance between me as the filmmaker and what’s in front of me. I need to feel the rhythm inside the material, and respond to it.”

These films that investigate the process of cinema itself, a process imbedded in environments and space. The short documentary films of Yi Cui offer a way to rethink augmentation as a process of bringing environments, sound, and place to the forefront of documentary aesthetics and politics.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (2021). She is Editor-at-Large of The Edge.

Header image screen shot from “Through the Looking Glass” (Yi Cui, 2017)