I haven’t thought about playing on the Brown High School girls basketball team in decades. But as I was thinking about the controversies surrounding the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) Women’s Basketball Championship — racism, hood-talk, great white-hopes — it took me back.

I am the daughter of anti-racist Communists who had just moved to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1964, at the height of the civil rights movement. My dad was going to teach at Atlanta University and Spelman College, both Black schools. My dad is white. I was mortified to be uprooted for my senior year of high school. I knew no one in Atlanta and I would live in the Black community where faculty housing was located, and my school was white, except for Clemsy Wood. He was the one Black student that had enrolled as soon as the schools were desegregated that year. We became friends, but that is another story. Anyway, I was lonely.

I wasn’t a very good athlete, but I thought it might be fun to be on a school team. So, I tried out and was accepted to play guard on the girls’ basketball team. I probably was your typical white girl when it came to sports, definitely not extraordinary. I played on the team for a few weeks and then my parents came to a game with some of their (Black) friends and colleagues from Atlanta University and Spelman. After that the coach decided I really was not good enough to play, and I probably was not, but that is beside the point. Remember high school? Then add race/ism to the mix.

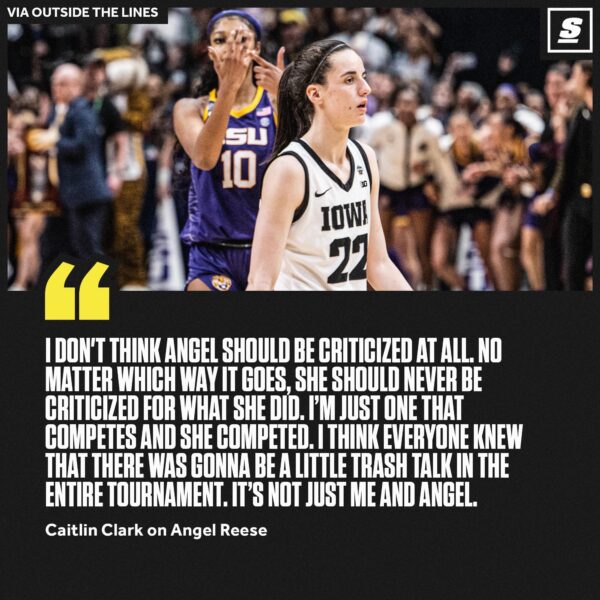

But to get to what I really want to talk about: As my text feed started filling up with notes from friends about how the coverage of the NCAA matchups was unfair, biased, even racist, I thought, “How could it not be?” This is the U.S. Angel Reese and the Louisiana State University team is almost all Black. Iowa’s team, and Caitlin Clark, are white. So hypocritical, racist news stories ensued when Reese talked trash in the same way Clark and other white athletes had.

Leading up to the NCAA final championship game, Iowa beat the unbeaten South Carolina team, coached by the amazing Dawn Staley. South Carolina is predominantly Black and Iowa predominantly white. And Caitlin Clark the star phenome is also white. Tons of the coverage was about her and her phenomenal game.

Caitlin is the perfectly imagined great white hope. Our culture usually does not have room for more than one star at a time, but the exclusionary focus on Clark could not be construed as anything other than a form of white privilege. As a white girl/woman she breaks the mold of the black female athlete. And when media spokespeople had started talking trash about her team Coach Staley warned: be careful how you describe my team and their strengths in unfair, racist ways.

White privilege often masquerades as white excellence. Caitlin Clark is not a masquerade, but the elevation of her stardom is as much white privilege as it is white excellence. On the court in the final game between Iowa and Louisiana it looked like Jim Crow-era segregation, Black against white. So, race may appear as the signifier to most of us, but I know that race never signifies without and alongside gender and its heteronormative underpinnings.

So, race/ism never exists — ever since chattel slavery and the rape of Black women — by itself. Racialized hetero gender underpins it all. These basketball players, so often assumed to be gay, or dykes, are reduced in this instance to their race. Racialized hetero gender and engendered hetero race is what people are seeing and thinking when they speak of race per se. Race itself is intersectional before it combines with our other identities. It should be lost on no one that coach Kim Mulkey, with her predominantly Black players, is also known for policing gender expression on her team. (Brittney Griner has spoken about her time at Baylor, coached by Mulkey, and her homophobic controls.)

Louisiana State University 2022-2023 Women’s Basketball Roster

Both teams are labeled women’s teams — whatever women means currently with queer and trans and gender diverse people. And Black women are constructed differently than white women. They are seen as oversexualized, overly physical, and a possible (sexual) threat. This is written on their bodies with no choice on their part. So when Angel Reese is called a ho or ghetto, she is being defined in and through a hetero misogynist and racist visor. Black women are never just Black, they are a particular construction of both and all. Race and gender are inseparable and yet distinct. It is why white women should also be enraged by these depictions of Reese. And it is in part why Black transgender women are killed with such impunity.

Let us think more about what intersectionality looks like on the basketball court. Black women’s bodies are Black and female and often constructed as poor before they are anything else. Class, sex, and race are never separate, even if distinct. Reese claimed a language that made it clear that she is not from the Black respectability crew, and that she’ll design who she is for herself and others, even if it’s ghetto. And it is somewhat interesting to see how race has silenced the homophobic trope that so often is part of women’s sports. Angel’s eyelashes just may anger all those who cannot figure them out.

So, yes, call attention to the racist tropes that are used to depict the women on the LSU team, but let us not forget that racism is always also embodied in sexism, cis culture, and class privilege. Do not get lazy and fail to see the complexity of the changes and the struggles that our world is so deeply embedded in.

I cannot think about all this and not wonder why with transgender fluidity there still are women’s teams per se, or women’s athletes. Of course I know what the expected answer is: there are biological differences that demand the segregation to make competition fair. But is that really enough to explain all this now?

The NCAA women’s title game was amazing. The arena was packed and millions watched from their screens. Is it possible that women’s sport will displace the singularity of male privilege, that male sport is the best? Mainstream media and news carry the men’s competitions at center stage even though all eyes seemed to be on this game. I am totally used to this kind of dismissal and misrepresentation of women in whatever arena, so the coverage, focusing on the catfight, so to speak, between Angel and Caitlin was just in keeping with everything contained in old narratives.

So much is changing. And so much is not changing. Old tropes misrepresent and make it impossible to really see. As I finished writing this piece, First Lady Jill Biden said she would like to celebrate the excellence of the Iowa team too and bring both teams to the White House to celebrate. And I thought, really? Is this whiteness speaking again? Let us heal the wounds of the loser, who does not usually lose? Or, is this the latest version of a “participation trophy,” so that no one feels bad, especially the white team? Or as one of my friends said: yet one more version of “all lives matter,” rather than Black lives matter? Jill, if you want to celebrate Title IX and all it has done, make a different celebration. This night belongs to LSU.

As I was saying, before the tweets about Jill interrupted: Reese needs more room to choose who she wants to be. Clark does too.

But Clark is positioned differently given the racism of the U.S. She needs to query how she wants to take on the white privilege that limits other players and help them change it. Instead of being a white hope, hope for abolition of unequal racial and gender systems of power and then let us see what full excellence looks like.

And by the way, there is no politically correct language here. My whole point is that the idea that you can contain gender and race meanings is wrong headed. It is impossible because of the fluidity and stubbornness of race, class, sex and gender, right now. And we live in the right now.

Thanks to several friends who know lots more about women’s basketball than I do for talking with me while I wrote this.

Zillah Eisenstein is a noted international feminist writer and activist and Professor Emerita, Political Theory, Ithaca College. She is the author of many books, including “The Female Body and the Law” (UC Press, 1988), which won the Victoria Schuck Book Prize for the best book on women and politics; “Hatreds” (Routledge., 1996), “Global Obscenities” (NYU Press, 1998), “Against Empire” (Zed Press, 2004), and most recently, “Abolitionist Socialist Feminism” (Monthly Review Press, 2019).