The Edge just published Dale Hudson’s fantastic piece “The World Is Burning — Whatever Tops the BFI’s ‘Best Films of All Time’ Won’t Help.” I’d like to stir some other ideas into this debate.

Hudson’s piece hits on some key issues in the world of film culture: lists are a problem.

Right now, in our current political moment around the globe, lists like this stand out as ludicrous exercises in the context of the multiple catastrophes we face.

In the context of a vast and urgent media culture extending past Europe, North America, and art cinema, any list at all seems like a throwback to a much less complicated time where “great films” were all that mattered.

The only lists I stand by are the ones that acknowledge their specificity and incompleteness through a radically inclusive project of multiple and endless list making.

I started the St. Andrews Playlist initiative to navigate the wealth of digital materials becoming available during the pandemic. It was wonderful that festivals and archives were going online, but how to begin?

The initiative employed the structure of lists to explore the circumstances and experiences of the lockdown with guides to television’s bottle episodes, disease in contemporary Chinese cinema, and the urgent media eruptions.

As the initiative continued, it opened up opportunities to explore issues, ideas, and lesser-seen cinemas and media with guides to Ecuador, indigenous women’s cinema, and the voices of West Papua. If curation constitutes an act of care as its etymology suggests, that care must be expansive. Canonical best lists so often are the opposite. They are restrictive.

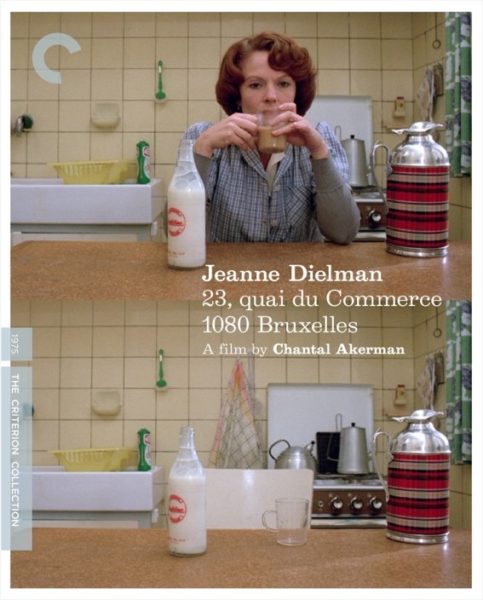

Given the excitement around “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975) as number 1 on the BFI list and Dale’s critiques of the film, I feel compelled to say a few things about it.

Poster for “Jeanne Dielman”

Dale gives the film a bit of a bad rap in this piece. To be fair, for me it is a rather an incomplete view.

I was one of those film people delighted by its appearance at the top of the list due to my affection for the film and especially for the outrage it generated on social media that revealed exactly what makes lists like this one such a problem.

That social media posters on various platforms railed against this film as undeserving without ever having seen it or even heard of it speaks to the arrogance imbedded in our cinematic and social/political history. I did not see the naming of “Jeanne Dielman” as a triumph as much as a joyful if utterly mild and limited disruption.

I feel compelled to respond to this critique of “Jeanne Dielman” which does not account for Jewishness. To characterize it as embedded in colonialism and bourgeois sentiment is to miss out.

Screen Shot from “Jeanne Dielman”

The relationship of Belgian Jews of Chantal Akerman’s generation to Belgium is a fraught one.

Or at least, so it seems from my perspective as a Belgian Jew, who unlike her mother was a natural born citizen of Belgium.

For my mother and her family, it was not so simple.

Born during the war in Anderlecht, she was nonetheless apatride or “without country” until she was 18. Her father told her this meant she was a “citizen of the U.N.” although none of us researched that claim.

When I inquired further she wrote to me:

“All I remember is that when I was 15, on holiday in a boarding house in Switzerland, an excursion was organized to Evian (in France), and I couldn’t cross the border because I had a visa for only one entry into Switzerland. So I spent the day at the border waiting for the other girls, and had a ball because a friend chose to stay with me.”

As a schoolgirl in Brussels, she experienced being marginalized as an outsider almost daily. Because she was Jewish, she had to stand outside in the hallway during the priest’s catechism lecture.

I remember asking my mother whether we were Fleming or Walloon. A teacher of mine asked me that question and I did not know the answer. In bafflement, my mother responded “Neither, we’re Jewish.”

This is a sentiment of unsettled immigrant status.

My grandfather had come to Brussels from the Austro-Hungarian empire from a shtetl in what is now Ukraine. My grandmother and her parents had immigrated from Poland and settled in Brussels. The occupation and war changed things: they were forced to hand over their business and then go into hiding. Following a public denunciation, my grandfather and great grandparents were sent to the camps. Fortunately, my grandmother who was pregnant with my mother was not included. I still agonize over not probing her survival story.

Following the war came resettlement, finding homes, and starting anew — but not quite belonging.

My family were displaced people. Trying to locate friends and relatives, the majority of whom were lost, occupied most of their time. This cloud of sadness, adjustment, and instability surrounded the Jews of Chantal Akerman’s generation. Arguments for their non-Belgianness were pervasive. They had come from D’Est where war destabilized all national boundaries. My mother’s answer made it clear ours was a different national story, especially from the perspective of her generation.

When I saw “Jeanne Dielman” for the first time, I recognized my own experience. I was 14 or 15 years old. I went to the Brattle Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, intrigued by the description of the film, which focused on a Belgian sex worker. What I saw was unexpected. I was entranced even then.

The mise-en-scene evoked the meticulously managed homes I knew. It is hard to know whether my family dedicated themselves to this intense organization of space to ensure belonging or to stave off the trauma infusing the corners of their lives.

Screen shot from “Jeanne Dielman”

In Jeanne’s apartment and in that of my grandparents, everything had its place.

The doors that separated each room amplified the segmentation of domestic space. Jeanne’s food preparation reminded me of how my grandparents cooked. These images conjure up similar feelings of heimishness (Yiddish for home). Later, in my first year of film studies at New York University, I noticed the fraying of Jeanne’s edges as a shirt was unevenly buttoned or the potatoes were burned. To me, these images expressed trauma on the domestic scale. The threat of coming undone loomed beyond the careful routinization of post-war life.

The fact that Jeanne (the character, not the film) does not share the language of her son exposes a story of migration and of Jewishness. Although Belgium is a nation with three official languages (French, Flemish, and German), this domestic schism resonates with so many immigrant families. “Bruxelles-transit” (1980), a Yiddish-language semi-documentary written and directed by Akerman collaborator Samy Szlingerbaum, explores this story of migration and (un)settlement more explicitly. It is an orphan film that deserves to be available on DVD or streaming and should have public screenings.

Poster for “Bruxelles-transit”

A lot is missed when writers critiquing or saluting the BFI Sight and Sound list paint over Jewish experience and limit themselves to the brushes of colonialism and whiteness.

There is room for complexity as we rethink cinema. There is room for seeing histories of the displacements of migration that made their way into some of cinema and inhabit the corners of the canon where we cannot see it. And although these broad strokes might work for the polemical dimension of Dale’s piece, they harbor problematic limitations.

So now let me share how social media can fuel useful collegial exchange and productive debate.

Dale responded to my intervention on Facebook with the following:

“Thanks for these insights into JD, which are whitewashed from all the excitement about the first woman director that I have seen, which is itself another instance of the colonizing power of single-issue feminism. My issues were less with the film than with the liberal discourse that change is possible without fundamentally redefining the bias of such lists. There is also a cannibalistic formalist or auteurist drive within these lists that erases all of the details that you mention. Everything becomes style.”

I wrote back: “Yes! It’s always about the discourse around the lists and films.”

To conclude: I still love the article and am grateful Dale wrote it!

I love lists even as I hate them. They generate energizing and productive dialectics.

These conversations and debates uncover and reveal more films, more practices, and more reflection on the films we thought we knew.

Leshu Torchin is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of St Andrews. Her experience as a half-Belgian, half-American Jew exposed her to very different narratives of the Holocaust. This background moved her to research genocide representation, resulting in the book “Creating the Witness: Documenting Genocide on Film, Video, and the Internet.” She continues to work on human rights in film and is starting a project on care and carelessness in the media industries. She hopes to revive the University of St. Andrews Playlist Initiative, currently on hiatus. Pitches are gratefully received. Contact her at: lt40@st-andrews.ac.uk