“Hundreds of people are dying today. Is cinema going to stay out of it?” demanded Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Sitting at a large desk clad in olive green military fatigues with the Ukrainian flag on screen left, Zelenskyy addressed the international crowd of film directors, actors, producers, publicists, and critics attending the May 17 opening night ceremony at the Palais des Festivals et des Congrès at the 75th Annual Cannes Film Festival via live feed.

As of May 28, the last day of the Cannes Film Festival, 6.7 million Ukrainians are refugees, 8 million are internally displaced, and nearly 4,000 civilians have been killed, according to the United Nations Ukraine Data Explorer.

The second largest country in Europe, Ukraine’s population is 44.13 million. The Russia-Ukraine war is the longest war in Europe since World War II.

“Again, then as now, there is a dictator. Again, then as now, there is a war for freedom. Again, then as now, cinema must not be silent,” Zelenskyy proclaimed.

World class, top tier festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, and Venice sport long histories of mixing together big budget Hollywood blockbusters, auteurist art cinema, independent film, documentaries, business, arts, and politics into a strange mélange of the market, commerce, art, and politics.

This confection is less about the politics or positions of a film festival, but instead, about festivals as nodal points for the convergence of the local and global, commerce and art, political struggles and the narcissism of star culture.

This year Cannes was no exception to these boomerangs between politics and art, tentpoles and Zooms.

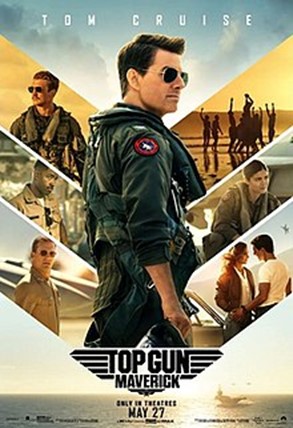

Zelenskyy’s powerful speech on Zoom about the Russia-Ukraine war screened in the opening festival ceremonies with Tom Cruise’s “Top Gun: Maverick,” a $170 million dollar Hollywood blockbuster de facto heralding the U.S. military with zero sense of irony.

Cruise received a surprise Palme d’Or, accompanied by a five-minute standing ovation. Eight fighter jets flew overhead, spitting out red, white, and blue smoke, the colors of both the U.S. and French flags. This anodyne spectacle happened at the same time as the continual Russian bombings of civilians occurring in a different time zone to the East. Two days later, the U.S. Congress approved a $40 billion aid package to Ukraine.

If Zelenskyy represents the current movement of infiltrations and permeations between independent, social, and commercial media, Cruise epitomizes both military and cinematic ossified nostalgia.

A remake of “Top Gun” (1986), the film features Cruise as a courageous test pilot for the US Navy. Images promoting the film sport a medium close-up shot of him determinedly piloting a fighter jet. In the visual context of news images of Ukrainian pilots fighting the Russians with older planes, the film offers an extreme absurdist fantasy of action-adventure films that advertize the masculinist phallic prowess of the U.S. military.

As escapist narratives, films like “Top Gun: Maverick” proffer a yearning phantasmatic that war happens in battlefields with men and machines, rather than war on multiple fronts on the ground, cyberspace, news flows, social media, misinformation, disinformation, surveillance, drones, intelligence gathering. The day after the opening of Cannes, the Washington Post ran a story exposing that the U.S. provided the Ukrainians with intelligence that led to the sinking of the Russian cruiser Moskva in the Black Sea.

Cruise also signals the pre-COVID melancholy of the transnational corporate media industry to hold on to theatrical screenings. With delays from COVID surges and multiplexes shuttered, Cruise, one of the film’s producers, insisted on a two-year wait in order to ensure a theatrical wide saturation release.

In his Palme d’Or acceptance speech, Variety reported that Cruise exhorted with triumphant glee “There’s no masks and we’re in a movie theater.” The film grossed $124 million in its first weekend, coinciding with the U.S. Memorial Day, which celebrates fallen U.S. military.

In an endless cycle of contradictions and fissures that now define the international media landscape, two feminist protests at the Cannes Film Festival present a counter to Cruise and his “Top Gun: Maverick’s” nationalist imaginaries.

At the premiere of Ali Abassi’s thriller, “Holy Spider,” twelve women in black formal wear stood on the steps of the Palais with raised fists. Smoke plumed out from their hand-held devices while they spread out a banner with the 129 names of women killed in France from femicide since the last Cannes.

And at the premiere of George Miller’s “3000 Years of Longing,” a woman dressed in the festival-mandated evening wear ripped off her dress. Her midsection exposed the hand-painted phrase “Stop Raping Us” and the colors of the Ukrainian flag to protest Russian rapes of Ukrainian women.

*****

Zelenskyy’s performance channels Brechtian dramatic style: direct address, logos and pathos, minimalist sets, reasoning and emotion, political struggle, technology, juxtaposition to open up dialectics and engagement. These zoom speeches break the fourth wall, powerful monologues of direct address, urgency, and action.

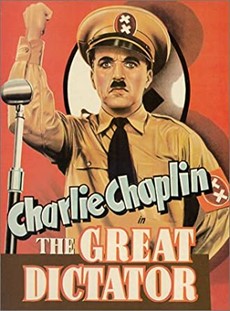

“We need a new Chaplin who will prove again that cinematography is no longer dumb,” insisted Zelenskyy.

Zelenskyy’s speech at Cannes enmeshes references to the history of cinema and television. This war during continuing pandemic and intensifying aggression necessitates conceptualizing media within a mise en abyme analytic, where media within media, stories within stories, and images within images circulate and morph.

His authentic and urgent delivery in direct address in medium shot in one long take jolts us into a recognition that a new way of thinking through media and war is necessary.

“Now there is not a single week passing of mass graves of killed and tortured people found in the territory where Russian troops were … 500,000 deported to Russia by force. Dozens of cities completely destroyed,” Zelenskyy elaborated.

But the Zelenskyy surprise appearance at the opening event is not an anomaly. The political has always been imbedded in Cannes.

“We continue fighting. We have no choice but to continue fighting for our freedom,” he insisted.

Zelenskyy’s Cannes speech alluded to the history of Cannes, started in 1947 during the post- World War II period. Cannes’ own history is deeply politicized and connected to war and fascism. The French launched it in response to the Venice Film Festival’s fascist bias under Benito Mussolini. The festival started in 1932 by the National Fascist Party in Venice. It is now the world’s oldest film festival.

In 1937, Mussolini manipulated the festival to prevent Jean Renoir’s anti-war masterpiece, “La Grande Illusion” (1937), from winning an award. It is a war film without any scenes of battle, the almost total opposite of “Top Gun: Maverick.” In 1938, the festival awarded best foreign film to Leni Reifenstahl’s Nazi-sponsored “Olympia” (1938). Furious, the French delegates decided to start their own festival in 1939, but World War II derailed their plans.

During the May 1968 protests, Cannes was suspended after five days. Four Nouvelle Vague directors — Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Claude Lelouch, and Louis Malle — went on stage. They demanded the festival be shut down as three million students and workers demonstrated in the streets of Paris.

In the last several years, the status of feature-length films on streamers has unleashed vociferous debate in France, a film industry with some of the largest support for cinema in the world.

French theater owners pressured Cannes to refuse to screen streaming films, a way to protect analog films projected in brick-and-mortar cinemas. But the pandemic, emerging media technologies, and streaming have disrupted the media landscape in tectonic ways. The New York Times on May 18 observed “Cannes sometimes seems like a throwback: a place where the big screen is so revered that you’d hardly know the outside world consumes art films on much smaller screens, if at all.”

Yet one of this year’s festival sponsors was TikTok, the six-year-old social media platform owned by Chinese tech company ByteDance. Previously, Cannes banned all social media and selfie postings from red carpet events.

But in what analysts interpreted as an inroad to reach a younger demographic and “techno-hipness,” Cannes initiated a partnership with TikTok and granted it exclusive livestreaming access. TikTok paid for the sponsorship deal, joining luxury brands such as L’Oreal, BMW, and Chopard.

But controversy percolated. Cambodian film director Rithy Panh resigned from President of the TikTok Short Film Festival jury, claiming disagreement “over the independence and sovereignty of the jury.”

****

Between pandemic, racism, and this brutal war, big and small media are now entangled in a much more complex ecology of layers and flows.

It is an ecology where amateur technologies like iPhones and Zoom can be mobilized by a Ukrainian president at war to report from the front and to defend the narrative of a country under attack, distributed to the world and circulated across as many platforms as necessary.

The binary oppositions between commercial media and independent media have become untenable because both are now more permeable and less solidified. The international media ecologies are more fluid, variable, and complex as Ukraine deploys not only weapons but social media platforms to control their own narrative and to combat Russian disinformation campaigns.

Mykhallo Fedorov, Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation, declared the Russia-Ukraine war “World Cyberwar I.” So consider this: Ukraine contacted Chinese drone company DJI to geofence its technology from working inside Ukraine.

Zelenskyy has used platforms to crowdsource for people to fight, donations, matériel. Since the war began on February 24, Ukraine’s social media channels have exploded with users. Twitter now has six times the number of users in Ukraine, at 1.9 million. Zelenskyy’s Instagram added 6.5 million in 30 days.

A March 17 article on CNET points out that Ukraine’s “tight focus” on social media such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook as well as videos and memes instead of television and publication has been critical to its success in controlling the war narrative. Zelenskyy has also produced selfie-style videos with a smart phone in direct address while walking the streets of Kyiv.

Now, Russia has more sanctions against it than any other country in history, perhaps connected with the Ukrainian social media campaigns to control the narrative with a human, accessible, urgent face condensing a populist democratic vision rather than the distancing of Putin at long tables and rambling press conferences.

Igor Novikov, a former Ukrainian presidential adviser, pointed out in a piece in Al Jazeera that Zelenskyy “is surrounded not by politicians but by ordinary human beings. Some of them come from his production company, some come from show business, some from the legal profession, but most of them have never had any previous experience in politics, and that gives them that willpower and courage to actually tackle the old system.”

Zelenskyy’s ever-present, persistent short Zoom speeches to governments around the globe such as the U.S. Congress, the Canadian Parliament, the British Parliament, the Saeima in Lithuania, the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Verkhovna Rada in Poland, the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia, and Malta via Zoom evidence small media as seepage. It moves like water, trickling into cracks in various media systems.

In this context, Zelenskyy’s Cannes speech constitutes not an anomaly but rather a continuation of a strategy of media permeation, infiltration, and intervention. Although garnering international press and entertainment industry coverage, his Cannes speech was one of many international Zooms beamed into places beyond Ukraine. They can be found in the video archive of the President of Ukraine.

For example, earlier in April, Zelenskyy addressed the Grammy Awards, the premiere ceremony promoting the music industry. He apprised the audience his country’s musicians were wearing “body armor instead of tuxedos.”

****

Zelenskyy’s speeches on Zoom and social media bypass official government press conferences, so pervasive in the Vietnam War’s “five o’clock follies” and the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. They circumvent commercial mainstream media such as CNN and the BBC.

Instead, they illustrate three essential emerging media reconfigurations and permutations.

First, they show how after two years of pandemic, the infiltrations and seepages between independent media and commercial media, between low-end amateur technology and high- tech gear, have intensified and multiplied. Even CNN and the BBC are using videos posted on social media as B-roll to show images of the battles and their aftermaths in Mariupol and Kharkiv.

Second, Zelenskyy’s Zoom speeches show how the media ecology of the war in Ukraine exceeds any simple binary opposition between mainstream and independent. Media collectives like Babylon ’13 documenting the war on the ground and posting on their YouTube channel show the granular, human side of the war beyond the maps of troop movements on CNN and the BBC narrated by ex-military officials. They offer small scale, regional stories instead of nationalism.

Babylon ’13, as an independent citizen’s media project formed during the 2013–2014 Maidan protests, also evidences how the war in Ukraine entwines the local and global, the national and transnational, as the world confronts wheat and oil shortages and million refugees. The use of social media platforms by the Ukrainian government and citizens alike bypass big media.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre, the national archive, shows films in subways serving as bomb shelters and offers free streaming of Sergei Loznitsa’s “Maidan” (2014). Ukraine boasts a long and rich cinematic history, reaching back to Dovzhenko and Dziga Vertov in the 1920s.

Third, there is a shift to an endless and dynamic mise en abyme, a story within a story, an image within an image, where references to cinema, television, and radio history get recycled and summoned.

Images of war done by amateurs on smart phones become visual evidence in addresses to governments, such as Zelinskyy’s speech to the U.S. Congress. The literal translation of mise en abyme is placed in an abyss, an apt metaphor for the Russian Ukraine war and Zelenskyy’s speeches to the globe that implore for help to pull out of the horrifying depths of Russia’s assault.

At Cannes, Zelenskyy’s speech quoted from Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator” (1940): “Greed has poisoned men’s’ souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed.”

He quoted from Frances Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” (1979) “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

He channeled the TV show M*A*S* H* (1972-1983): “war isn’t hell, war is war, hell is hell and of the two, war is a lot worse.”

All of these quotes and allusions to movies journey through a media mise en abyme across borders and languages. Zelenskyy himself embodies his own mise en abyme, a comedic actor in Ukrainian Rom Coms such as “No Love in the City” (2009), No Love in the City 2 (2010) “Me.You.He.She.” (2019) and in a TV show, “Servant of the People” (2016-2019), where he portrayed a reluctant president, now streaming on Netflix.

As reported in Variety, Zelensky redirected earnings from his Ukrainian animated film Gulliver Returns (2022) to support Ukrainian defense. Based on ideas from Jonathan Swift, Gulliver is large in heart, not size, returning to Lilliput.

In the current media landscape, Liliput might function as a metaphor for Ukraine, a mise-en-abyme of World War II stories of destruction, Stalin’s genocide of five million Ukrainians during the Holodomar (the Great Famine) of 1932–33, and other Russian incursions in the 21st century such as Crimea, Syria, Georgia, Chechnya, Donbass.

****

At Cannes 2022, the massive screen spanned the stage, provoking visual and conceptual contradictions that mark a Brechtian-inflected dialectics entwining politics and art:

Zelenskyy at war, Tom Cruise awarded a special Palme d’Or and then a screening of “Top Gun: Maverick.”

Zelenskyy in fatigues and beard, the festivalgoers in designer clothes and styled hair and make-up.

Zelenskyy alone, the festivalgoers in a large, unmasked group.

Zelenskyy in his office, festivalgoers in a massive theater.

Zelenskyy at war, festivalgoers celebrating the return to an embodied festival after the pandemic.

Zelenskyy beamed in over Zoom with low-end technology in one long take, Cannes a showcase for art cinema and tentpole special effects films like “Top Gun: Maverick.”

Zelenskyy taking his message to the globe via low-end amateur technology and social media platforms, Putin delivering rambling speeches and sitting at one end of a long table.

Zelensky in a minimalist set and live, the films hyper-produced with their roll out with stars and auteurist directors carefully crafted for neoliberal capitalism.

These dialectics define the layers of this constantly shape-shifting media ecology. They inform any reading of Zelenskyy’s continuous daily speeches on Zoom to governments around the world and to citizens of Ukraine, all eventually archived on the government’s website. These speeches are inflections of not only social media campaigns but exemplify Brechtian strategies mobilized for 21st century war where hearts, minds, and military and humanitarian support must be mobilized locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally.

****

Soon after Russia’s invasion, some Ukrainian producers and directors asked international film festivals to boycott Russian films.

Cannes decided to not accept delegates from the Russian government. However, it would allow directors, a continuation of its decades-long embrace of tourism and auteurism as twin engines of the festival’s political economy. At Cannes 2022, Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov screened “Tchaikovksy’s Wife” (2022), a story about the composer’s wife who loses her mental health when she discovers her husband is gay.

Two Ukrainian films unfurled: internationally acclaimed auteur Sergei Loznitsa’s “The Natural History of Destruction” (2022), a compilation documentary about carpet bombing during World War II, and Maksin Nakonechyi’s “Butterfly Vision” (2022), a narrative about a Ukrainian aerial reconnaissance expert released from months as prisoner in Donbass. Both exemplify mise-en-abyme’s of war stories infusing cinema no matter the mode or genre, inserted into the present moment of instability.

In March 2022, Nakonechyi argued “starting with [2014] Revolution of Dignity, we have been experiencing these events through images, and now, we can talk about ‘the online war.’”

In May 2022 at Cannes, Nakonechyi, the producers, actors, and production team of “Butterfly Vision” stood defiantly on the red carpet leading into Salle Debussy on the steps of the Palais to protest social media blackouts of the Russian Ukraine war, another example of the persistent mise-en-abyme tropes and strategies of this brutal war.

An air raid siren blasted, reminding festivalgoers of the soundscape alerting citizens when a Russian attack is imminent.

They held translucent images of a crossed-out eye, the logo used on social media when content is deemed too sensitive or disturbing. Graphic war-related content has been hidden on social media. They held a banner that read “Russians kill Ukrainians. Do you find it offensive or disturbing to talk about this genocide?”

Producer Darya Bassel told Variety that “It’s not about coming to Cannes to [have fun] or coming to Cannes to do business. For us, it is only about delivering the message to the world. We couldn’t imagine using this time for anything else.”

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (Indiana 2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (Indiana, 2021).