The Edge has leapt into the debates ignited by the December 1 publication of the Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time 2022 list currently crackling across social media.

For film historian Dan Streible, this was his first invitation to vote. Since his ballot annotations were written in August 2022, they should not be read as a reaction to this week’s debates. We publish his list here to show that some cinephiles were thinking out of the box and beyond the art cinema canon before the current debates erupted. See The Edge’s full statement on Sight and Sound’s list here.

Identifying the “Greatest Films of All Time” requires reconsideration in 2022, for at least two reasons.

We now have knowledge of and access to many types of films not readily available before: nontheatrical, amateur, sponsored, and other orphaned works. Are some great? Yes. We also better understand that previous canonization took place under circumstances that limited views of the possible as well as the great.

Films I might put on a longer list include undeniably great works from the classical canon (“Citizen Kane,” “Casablanca,” “Persona,” “Late Spring”), a newer canon (“The Gleaners and I,” “Killer of Sheep,” “Do the Right Thing,” “Daughters of the Dust,” “Sans Soleil,” “Mother India,” “Wings of Desire,” “The Thin Blue Line”), and other categories (shorts by Helen Hill, Les Blank).

A great and influential film such as “Man with a Movie Camera” must now be recontextualized and celebrated for different reasons than in the past: “Dziga Vertov” is a signature for the inseparable duo of Elizaveta Svilova and Denis Kaufman. And it is largely a Ukrainian work produced by a Ukrainian studio, shot in three Ukrainian cities, by a filmmaker who took a nom de cinema from Ukrainian words.

My ten selections are mostly non-canonical, even unfamiliar.

Most are not feature films and not the work of auteurs. However, each is great, which is to say well-wrought, highly creative, distinctive, original, memorable.

These are films that were thrilling to see the first time and which reward repeated viewing. Each came as a surprise because it was unlike the kinds of films of which I was aware. To be sure most come from archival sources rather than commercial distributors. It is the work of preservation and restoration that allows us to see them at all.

But this is not a list of obscure objects or arcana. These are films that merit wider distribution, that many viewers will appreciate and even love. To borrow a phrase Chris Marker uses in the English-language edition of Sans Soleil, these films are “things that quicken the heart.”

“New York Street Scenes and Noises–outtakes”

U.K. Whipple and Theodore Z. Rickman, U.S., 1929

Twelve minutes of early synchronous-sound newsreel footage from the Fox Movietone News archive (University of South Carolina Moving Image Research Collections). Seeing and hearing Manhattan in long takes is not only enchanting, 21st-century audiences experiencing a 35mm print projected say it’s transformative. Film historian Tom Gunning said it changed his conception of cinema.

Screen grab from “New York Street Scenes and Noises” (1929)

One sequence records technicians in Times Square, with its giant movie marquees and billboards, measuring sound levels for the NYC Noise Abatement Commission. “The noise in Times Square deprives us of 42% of our hearing,” one declares.

But the noise becomes Cageian music in a sequence shot from atop a van moving slowly down “Radio Row” in lower Manhattan. Truck motors and ahooga automobile horns intermix with clopping horse hooves. Someone whistles for a yapping dog as a pile driver whangs amid steam shovels beneath an elevated train. A variety of music wafts from radio shops as the camera tracks down the street. When the van stops, an army of men in topcoats and snap-brim hats stares silently into the camera as a warbling soprano voice overtakes the soundscape. A jump cut switches from “Rigoletto” to syncopated horns in an Ellingtonian jazz orchestra. A time capsule of modernity.

Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story

Todd Haynes, U.S., 1987

Not just a cult work but a major aesthetic achievement that has grown richer as layers of meaning accumulate.

Haynes did not clear music rights for this independent/student film, making its commercial release untenable. However its highly original and entertaining cinematic qualities created an audience of devoted viewers who made it a cult object via VHS bootlegs and subsequent on-and-off the internet sightings.

Screen grab from “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story” (1987)

Part of the fascination for “Superstar” lies in its illicit status, but it remains a powerful work with several registers. It’s a fan’s tale of the pop singer’s tragic death from anorexia; a melodramatic and educational docu-drama that uses modified Barbie dolls instead of human actors; an admixture of narrative and essay films, with a harmonic blend of mockumentary, queer, found-footage, and avant-garde modes. Now that Haynes, the Sundance Institute, and UCLA Film and Television Archive have done a full-fledged film restoration, big-screen exhibition might emerge in the coming decade.

“Light Cavalry Girls”

Shen Jie, China, 1980. Qing qi gu niang 轻骑姑娘, also translated as “Light Cavalry Girl”

A literal and cinematic joy ride, this short documentary profiles the Bayi Women’s Light Motorcycle Team, a unit of expert riders in China’s military.

“Light Cavalry Girls” (1980). Source: Moving Image Research Collections, University of South Carolina

A journeyman director made this within the apparatus of Beijing’s Central Newsreel and Documentary Film Studio. The wordless sports film is uncharacteristically exuberant for a state-supported enterprise, particularly one produced soon after the Cultural Revolution.

Mobile cameras follow the anonymous riders on a nonnarrative series of increasingly dangerous maneuvers: up and down stone staircases, through water, through fire, and standing atop their dirt bikes like balletic daredevils. The final sequence is a bravura display of stunt jumps shown in slow motion, with rhythmically edited sound and picture. Extreme low-angle shots of multiple cyclists framed midair create the sensation of this badass brigade taking wing and flying away. (See bootleg videos on bilibili.com.)

“The House Is Black”

Forugh Farrokhzad, Iran, 1962. Original title: خانه سیاه است/Khaneh siah ast

A moving, poetic, educational, sponsored documentary about a leper colony in Tabriz, Iran, directed by a young Iranian woman who never made another film but was regarded as a leading poet of the Persian language upon her death at age 32.

The fact that “The House Is Black” came to be in these circumstances was surprising, even unlikely. Its taboo topic adds to that sui generis status.

Poster for “The House is Black” (1962)

Little known before the 21st century, its aesthetic power has led critics to conceive of it as an essay film made before we used the term and an anticipation of the Iranian New Wave cinema that did not yet exist. But this context is not essential to seeing it as a beautiful work about an “ugly” subject.

Farrokhzad’s own voice whispers verses blending sacred texts from both the Koran and the Hebrew Bible with her original poetry, while we watch unblinking black-and-white footage of lepers living with varying stages of the disease. Filmmaker Hollis Frampton introduced cinephiles to the linguistics term hapax legomenon, an utterance occurring only once in a corpus or language. “The House Is Black” is that rare thing.

“The Flying Train”

Unknown, Deutsche Mutoskop-und Biograph, Germany, 1902

Among the dozens of recently restored films made with the proprietary Mutoscope and Biograph large-format cameras before 1903, this two-minute wonder stands out.

Screen grab from “The Flying Train” (1902)

Even experienced silent movie watchers are wowed by the high resolution of these recordings created on 68mm film, literally near IMAX quality.

“The Flying Train” was an internet sensation in 2020, when the Museum of Modern Art put it on YouTube, saying rightly “the footage is almost as impressive as the feat of engineering it captures.”

The German Schwebebahn was a then-new electric elevated railway that suspended train cars beneath its rails. Filming long takes from moving vehicles — phantom rides, as the genre was known from its birth in 1897 — famously created a thrilling sensation. By seeming to suspend passengers/viewers in midair, “The Flying Train” amplifies the thrill.

The German company’s cinematographer remains unidentified. The English title comes from the 1902 American Mutoscope and Biograph catalog, but the thrill-ride first appeared on screen as “Eine Fahrt auf der ersten deutschen Schwebebahn zwischen Vohwinkel und Elbersfeld” (A ride on the first German suspension railway between Vohwinkel and Elbersfeld). Scanned at 8K, these 68mm originals outshine the supposedly “upscaled” versions proliferating on YouTube.

“La Venganza de Pancho Villa”

Felix Padilla and Edmundo Padilla, U.S./Mexico, 1930-36

The father and son Padilla duo created this nearly hour-long silent compilation using a wide variety of 35mm prints they acquired working as exhibitors in El Paso, Texas, and as itinerants along the U.S.-Mexico border as early as 1916.

Poster for “La Venganza de Pancho Villa” (1930-36)

Loosely structured around the life General Villa during the Mexican Revolution, the Padillas re-edited their film many times. The surviving work resembles a modernist collage more than a compilation documentary of the era. Its pieces come from newsreels, serials, features, and other footage depicting the revolution in both factual and fictional forms from both American and Mexican sources.

Some intertitles are in Spanish, others bilingual, with English-Spanish texts. These include new title cards and those taken from commercial prints.

The crazy-quilt texture of “Pancho Villa’s Revenge” (as it is also known) is completed by an original scene the Padillas filmed at the El Paso-Juárez border. With amateur actors, they stage a reenactment of Villa’s 1923 assassination, which took place in Parral, Mexico, some 600 kilometers away. Still photographs of the actual corpse punctuate the end. “La Venganza” shows us an idiosyncratic cinematic creativity at work far from the film industry’s imagined center.

“Shoes”

Lois Weber, U.S., 1916

More than any other feature film of its era, “Shoes” still plays effectively to contemporary eyes and minds.

Lois Weber’s deft direction of a “social drama”/silent melodrama and Mary MacLaren’s restrained performance as a sexually exploited shopgirl create empathy for the teenage protagonist, Eva.

Poster for “Shoes” (1916)

The restoration by Eye Filmmuseum and Milestone Films allows us to absorb the film’s emotional conclusion despite the severe physical deterioration evident in the final reel. The unstable images serendipitously align with Eva’s tearful breakdown.

“Think of Me First as a Person”

Dwight L. Core Sr. and George A. Ingmire III, U.S., 1975/2008

The power of amateur cinema is nowhere more apparent than in this love letter from father Dwight Core to his son Dwight Jr., born with Down syndrome in 1960.

Its eight minutes condense 15 years of home movies showing the everyday life of the son, with a voice-over narration by the father. He fondly describes his son’s personality and recalls the pain of being separated when the child was placed temporarily in institutional care.

Screen grab from “Think of Me First as a Person” (1975/2008)

Core recorded his voice on a VHS tape some years later; his grandson George Ingmire found the elements of the unfinished work in the family attic. In 2008, using the filmmaker’s notes, he married the narration to the edited 16mm film, added sound elements, and with the pro bono aid of Haghefilm laboratory produced a 35mm print.

This unusual high-end treatment aside, the rawness and sincerity of “Think of Me First as a Person” capture the lived experiences of a “special needs” family in a way no professional film could.

“De Cierta Manera”

Sara Gómez, Cuba, 1977

Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC) was born with the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and generated an innovative series of films that excited the world.

The only woman making films there and one of only two Afro-Cubans, Sara Gómez directed some 20 films in a dozen years before her death at age 31 in 1974.

Poster for “De Cierta Manera” (1977)

Her only feature-length work, “De Cierta Manera,” was released posthumously. A blend of documentary and fictional narrative, it deals forthrightly, creatively, and radically with the problems confronting marginalized people in a postrevolutionary society.

Restored by Arsenal in 2021, it is now available from Janus Films. With several Gómez documentaries now being restored by ICAIC and the Vulnerable Media Lab, the world will soon get to rediscover and appreciate the work of this neglected filmmaker.

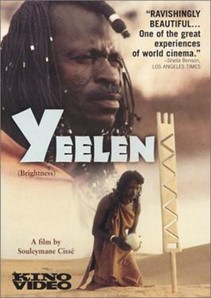

“Yeelen”

Souleymane Cissé, Mali, 1987

Poster for “Yeelen” (1987)

Also released with the English title Brightness, this mythic tale from Mali is proclaimed as a landmark of West African cinema, in part because of its success in reaching a global audience.

But it can hardly be consigned to an “art house” category.

Set in a precolonial if not timeless past, “Yeelen” spins out of a struggle between a father and son, but it does not participate in narrative modes that can be easily translated. It assumes a cosmology and spiritual or magical forces not explained for Western viewers.

Yet Cissé’s invention of a cinema unique to its point of origin possesses visual and musical qualities that engross audiences regardless of their ability to comprehend the world it creates.

Dan Streible teaches film history in the Department of Cinema Studies at New York University Tisch School of the Arts and is an associate director of its Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program. His research focuses on “orphan films,” neglected works outside of the commercial mainstream. Since 1999, he has organized the biennial Orphan Film Symposium, first at the University of South Carolina, then at NYU. The four-day event gathers scholars, archivists, curators, artists, and others devoted to the study, preservation, and use of archival moving images. See wp.nyu.edu/orphanfilm to learn more.