We are living in one of the most exciting times in the history of independent documentary.

The entire field is undergoing massive shifts in form, interface, technology, conceptualization, use, and topics. Documentary is at a turning point of radical disruption.

This new period of documentary crackles with intellectual and political excitement. It breaks open new strategies for cocreation, image-making, accessibility, where a project lives, and how a work is used and mobilized in communities. Interactive, participatory modes counter legacy media hierarchies of directors and makers — and prevail.

The disturbances that push documentary into new terrains also require thoughtful consideration and exploring new strategies and epistemologies. We must ask if it is productive to hold on to previous conceptual models from the analog era of documentary that de facto assume a fixed object such as a film or video.

Shape-shifting Tactics, Not Technologies

Fluidity, interaction, iterations, cocreation, and shape-shifting infuse a wide range of new media documentary forms. They require new kinds of provisional analytics and epistemics.

In the last ten years, documentary has stretched into myriad forms across many platforms, far beyond the “flatties” of analog theatrical or streaming films. Digital interfaces such as the web, installation combining analog and digital interfaces, 360-degree films, algorithmic structures, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), and more recently Augmented Reality (AR) provided affordances that push us to rethink the purpose and use of documentary anew.

However, caution is required so that we do not default to a technological determinism that locates these massive changes in documentary practice and theory inside machines. Instead, these new developments recalibrate and rewrite the relationships among content, analysis, immersion, humans, nonhumans, participants, politics, and place.

For instance, the technical term “augmented reality” presents two problematics. First, it situates itself in technology rather than in concepts and politics. Second, the very term “reality” is hotly contested.

Instead, we propose dropping the term “reality” with all its tricky politics and foggy assumptions to suggest that this emergent documentary practice be renamed Augmented Documentary (AD).

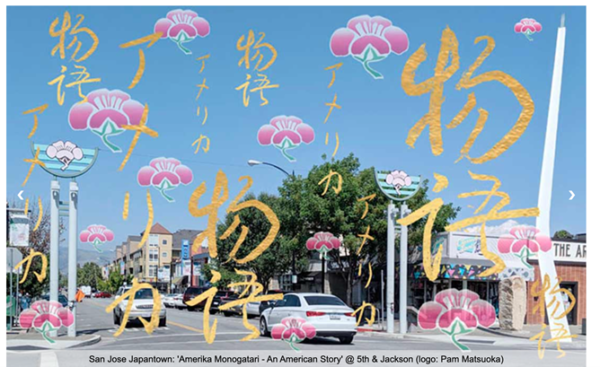

In contrast to the big budget feature-length or multi-episode documentaries coming to us via corporate streamers which focus on characters and story arcs, Augmented Documentary locates itself in place. As a result, it moves from the temporal with time lines, causality, and arcs to the spatial, complex with places, people, the nonhuman, mapping, and encounters. For example, “Hidden Histories,” initiated by Susan Hayase and Tom Izu, is a community-based project employing AR technology to engage the public with art inspired by the events and stories of San Jose’s Japantown.

AD moves from people to place, from individual to ecosystem, from a linear to a configurational structure, from a straight line to something more like a spiderweb, from one technological interface to many, from the director to the user and co-creative modalities.

Augmented Places

Augmented Documentary, or AD as we are calling it here, moves away from the Western narrative concept of characters, conflicts, and climaxes to locate itself in a specific place, a bounded territory.

AD does not create imaginary spaces to float in the way VR does, where we can fly, dive, move, or merge in our headset. AD approaches place as an area to amplify and complicate with layers of histories, stories, ideas, humans, nonhumans, across multiple timelines.

AD proposes not only an immersion in place, but an amplification of place that takes what appears two-dimensional such as the land or the water and builds out more layers.

AR is a platform for artists who explore the spatiality of stories and use augmentation to reveal the power dynamics of place. AR tools can create AD projects.

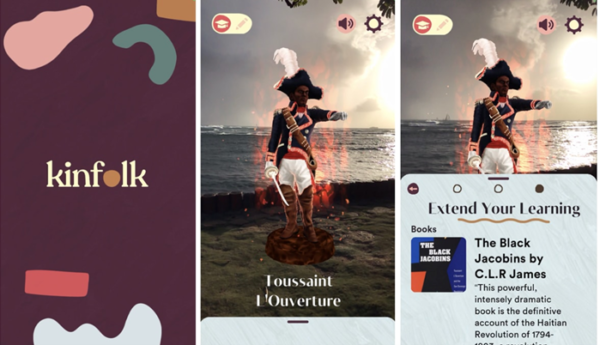

One example of Augmented Documentary challenging power in place is “Kinfolk AR, Rewriting History.” Through “Kinfolk,” Glen Cantave and his team marshal Augmented Documentary to challenge the dominant narratives of existing American monuments and to build awareness around black and indigenous heroes.

In a panel hosted by MIT Open Documentary Lab on “Layers of Place,” Glen suggested that the political process of legally removing a confederate statue from a public space requires time, patience, and political will. Meanwhile his App offers an immediate and playful re-staging of the public power requiring only our imagination. As he explained, AR offered a quick and exciting way of excavating centuries of dehumanization.

Cantave partnered with local artists from Winston Salem to develop a series of Black and Indigenous Icons such as Maya Angelou, Ruth Revels, and Annie Brown Kennedy that can be activated in a chosen place. Users can change the shape and scale of the statue, listen to a short biography of the person, and even record their impressions after the experience.

The App is part of a larger initiative to bring black history into the public realm and into curricula in a meaningful way. Beyond the playful re-mediation of a monument, users are encouraged to dig deeper onto a companion website for pictures, documents, or videos. The App is a prompt to gather knowledge and people in place through companion walking tours.

“Kinfolk” is designed to unsettle dominant place-based histories. It asks users to use their imagination to re-think the spatial power of a monument.

Twisting, Enmeshing, Reshuffling

AD produces entanglements.

It rejects the simplification of any place into soil and water and nature. It is a pathway, a provocation, a passage to explore. Rather than the straight line, AD offers a process of entangling in order to bring together the natural and the built, the human and the nonhuman, the present and history, the political and the personal, the digital and the embodied.

AD is an active process of replacing binaries with layers, sediments, and folds. It’s about probing how different environments, ideas, imaginaries, places, politics, practices, registers, and species twist into and enmesh with each other. Dispensing with narrative structures, linear constructions that depend on conflict, climaxes, arcs, and resolution, Augmented Documentary is about twisting time and space as a radical process of reinvention.

Artist Tamiko Thiel argues that augmentation has the power to transform our mobile devices into “ARscopes” allowing us to perceive parallel and overlapping dimensions. She uses augmentation to visualize stories that are disappearing or are simply outside of the public imagination.

In 2011 Thiel began working with augmentation posing the question, “what happened here?” For over a decade she has developed large scale AD installations to stage ephemeral environmental entanglements in place.

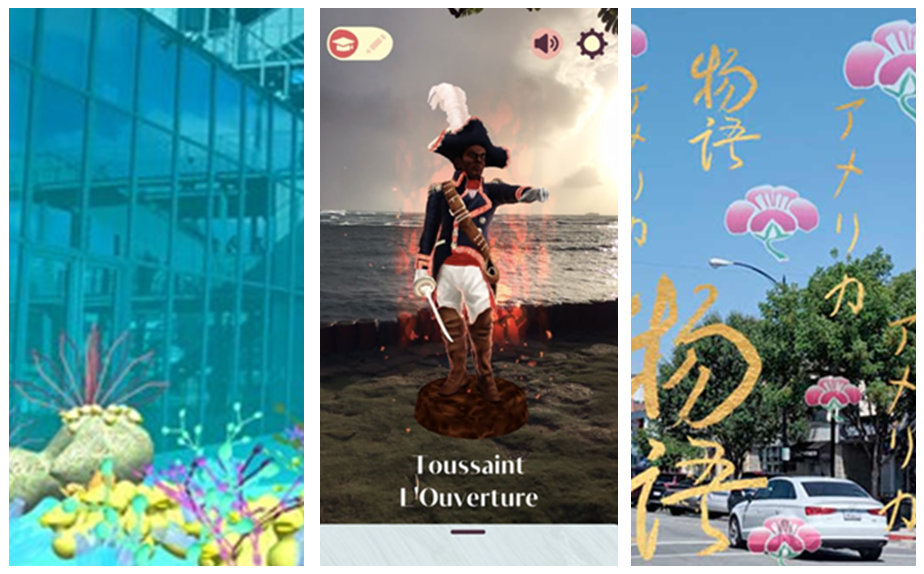

She developed “Unexpected Growth” (2018) to examine the entanglements of plastic proliferation and coral bleaching for the Whitney Museum. Here she used augmentation to harvest coral growth by combining coral animals and plastic. Increased user engagement over the course of a day caused the coral growth to bleach, forcing users to contemplate the impacts of human interference on our reefs and local surroundings.

She galvanized augmentation to shapeshift space in “Evolution of a Fish” (2019). In this large scale outdoor augmented projection, Thiel offered users iPads to move fish around an ephemeral underwater reef. However, interaction has a cost — increased interaction transformed fish into plastic.

In both installations, Thiel used interaction and augmentation to draw attention to the tensions between inside and outside, engagement and interference, play and disaster, present and future, natural and artificial.

Tamiko created her own software program called ARpoise and has trained and engaged other artists and communities. She deploys augmentation strategies to explore places in transition and places holding emotional value to her and her extended community such as Japantown in Seattle.

With her mother, Midori Kono Thiel, she developed “Brush the Sky” (2019), an augmented project and walking tour that places Midori’s calligraphy in selected sites significant to the Japanese community of San Jose, California, such as the Japanese American Museum. The tour also features informal sites such as a garden or street intersection referenced on a 1915 San Jose map to mark the expanding Japanese American community.

AR vs VR

Augmented Documentary projects are resolutely place-based and located in the physical world.

Augmentation is typically associated with the more industrial, corporate, and manufacturing term Augmented Reality (AR) which uses mobile apps, audio, and other devices to intensify and deepen one’s engagement and interaction with a particular place. Augmented Documentary (AD) projects do more: they conjure layers of history, cultures, struggles, buildings, and people.

AD’s located-ness stands in contrast to Virtual Reality’s (VR) denatured disembodiment and abstractions that surround the user in a virtually constructed space. If VR fashions new spaces to explore alone with a headset, Augmented Documentary puts the user into place with others, entangling the virtual with the real. Put another way, VR is place-agnostic whereas Augmented Documentary is place-centric.

Questions of place — the regional, local, and hyperlocal — have taken on new significance amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, migrations around the globe, and war in Ukraine. The invisibility of viral spread and anxieties over contagion, quarantine, and travel limitations intensify relationships with the small, accessible places where we live and work. Migration and war show us that places are connected to other places through politics and people.

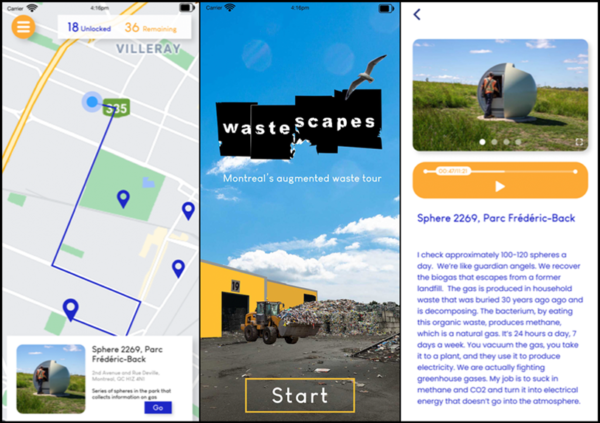

Liz Miller shifted her evolving VR documentary practice to Augmented Documentary during the pandemic when getting outside and connecting to local histories and places became a priority for her and her students. Liz and colleague MJ Thompson developed the App as a companion to a field course entitled “WasteScapes” (2021). The App guided students to sites with entangled histories such as former dumps, underground waste infrastructures, or repurposed waste lands in an attempt to rethink use, reuse, and our cavalier relationship to wasteful consumption. In “WasteScapes,” being there matters: short audio narrations and photos are unlocked only when someone visits a place.

The practice of being there constituted an essential part of making the App, requiring multiple visits and writing in place. The project permitted Miller to think beyond fixed representation toward heightened sensory awareness, observation, and co-creation with place. The App invites users into an ever-shifting assemblage of sensation and story.

Learning with the land also supported Miller’s ongoing work combining locative media with decolonizing pedagogies to revisit buried histories and to explore how memory and sensory observation bring the past into a more mindful present.

Using Augmented Documentary tactics, Miller convened walking and cycling tours for her students to co-create knowledge with others invested in these places. The project invites users to notice and respond to the micro and macro variabilities in local landscapes in order to discover tensions and orientations around place and screen, local and global, sensory and sensation.

Augmentation as Community-led Process

Augmentation implies increasing the size of a thing.

In music theory, augmentation refers to lengthening the time value of a note. In new media, Augmented Documentary projects deploy strategies of augmentation to generate richer, more complex layers of historical thinking that lengthen time from the present to the past and the future.

Augmented Documentary moves toward thinking in collaboration rather than using media to interrupt, intervene, remake, rebuild, or erase our sense of place. Cocreation strategies bring participants into a project in many ways, whether as community groups, co-makers, or participants in execution and use. These strategies of augmentation that invite more voices, perspectives, ideas, and people into both the project and the space.

Augmented projects bring together participants, places, technologies, archives, and histories in a community-led, multi-platformed process. These projects propose new ways of doing cartography as an embodied, living, and iterative practice that is constantly changing and responding.

In their 2021 Visible Evidence panel entitled “The Politics of Augmented Places: Hyperlocal Landscapes in Emergent Forms of Documentary,” Liz Miller, Topiary Landberg, and Dorit Naaman argue that augmentation enmeshes bodies, places, and technologies to produce polytemporalities, multiple senses of time and histories.

They locate augmented place-based work in the long histories of hiking, land art, biking, walking tours, and radical cartography as a way of thinking with the land. To think with the land is one very provisional way to move beyond extraction.

On the MIT Open Documentary Lab on “Layers of Place,” media artist Jackson 2Bears speaks to how AR offers an opportunity to establish “relational communication with people at place.” He suggests that Augmented Documentary offers a non-extractive storytelling form because the story stays in the place.

On the same panel, Halsey Burgund discussed his project “Bog People,” an evolving contributory Audio Augmented documentary project that uses augmentation to accentuate and accompany biologists and educators working together to facilitate the transition of a former Cranberry Farm into a more natural habitat.

The site, known as Tidmarsh, is a living lab with a mission to restore a former cranberry farm into a watershed restoration project. To develop the project Burgund used his open software program Roundware, a contributory audio augmented reality tool. He has placed site-specific interviews and sound compositions in strategic locations throughout the landscape so that a visitor can explore a range of perspectives about former uses and contemporary connections to the land. The App offers visitors a chance to contribute their own impressions and stories of the place.

AD offers a tool to convene people in place to explore its repressed histories. It holds the potential to revisit a shared place or to create a new space.

Microlocal Scale

Focusing on the scale of the microlocal, Augmented Documentary projects create pathways and forks for mediated dialogues between the human and the non-human and between nature and the built environment.

AD leads us to get closer to neglected, overlooked, in transition, or normalized places and sites to see them again in new ways. It deconstructs our preconceptions to loosen us up into exploring new interactions.

Augmented Documentary projects suggest a three-stage malleable process of how to think with place in an environmental way.

First, they engage micro-places that are entangled environmentally.

Second, they use conceptual thinking, innovative aesthetics, and different media modes to disentangle and understand more deeply.

Third, and finally, these projects entangle once again to produce new formations, new creative interventions, and new maps.

What if?

Augmented Documentary operates in a speculative and playful dimension. It shifts away from fixed media forms and structures. Its subject is place. AD disrupts how we experience and think about place. It asks us to pay attention.

It prods us to consider a question not often asked in traditional narrative documentaries: What if?

These emerging forms of Augmented Documentary ask us to consider the future. What if we thought about place differently? What if we imagined new sustainable ways of interacting with place? What if documentary offered an invitation rather than a declaration? What if we called for participation?

Augmented Documentary suggests a method and prompts us to co-create new connections to place. In a world saturated with commercial media across large and small platforms, it offers a way to be playful and have fun with Apps. Mobile phones transform into magic wands that give us a taste for other time frames, other possibilities.

AD pushes boundaries of where and how to experience documentary: with outdoor installations, public murals, ephemeral monuments, graffiti, or even as portals to other platforms.

These emerging forms of independent documentary mobilize a conjunction with enormous political potential: augmentation plus mobility. Augmented Documentary moves from questions of representation so imbedded in analog long form documentary toward continually changing and adapting relations with place.

Rather than conclusions, our thinking about Augmented Documentary leads us to questions:

How does Augmented Documentary deal with small histories and stories in place?

What kind of relations between user and place does Augmented Documentary invite?

Elizabeth (Liz) Miller is a documentary maker and professor in Tiohti:áke, Montreal who uses collaboration as a way to connect personal stories to larger social concerns. Her multi-platform documentary projects address issues related to climate change and environmental justice. Her book “Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice “(UBC Press, 2017) draws on conversations with practitioners across cultures and disciplines.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (Indiana 2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (Indiana, 2021).