In September 2022, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” (“Space Opera Theater”) by Jason M. Allen won a blue ribbon at the Colorado State Fair.

Outrage ensued. The involvement of an AI software called Midjourney offended many critics.

Allen never wielded a paintbrush or mixed pigments to produce his prize-winning artwork. Instead, he typed words and phrases into a text field and clicked “enter.” In response, the Midjourney software returned a picture. Allen printed the picture to canvas.

“Theatre D’Opera Spatial” thereby joined works ranging from Daguerre’s portraits to Duchamp’s urinal and Warhol’s soup cans that raise the question of what we mean when we use the word “art.”

A number of software products that “assist” in creative endeavor are entering the market.

Companies like OpenAI, Stability AI, and Midjourney have made their software available to the public. As a consequence, we are beginning to see a proliferation of AI-generated paintings, poems, short stories, essays, and even recipes. Not surprisingly, these outputs also provide data useful for refinement of the software.

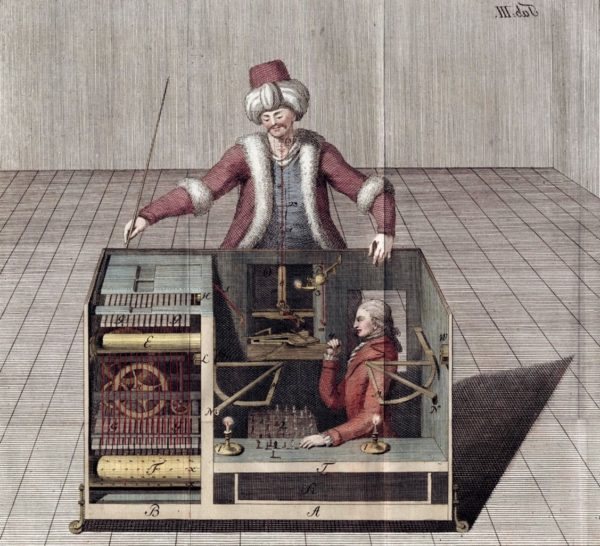

Wolfgang von Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk

Ultimately, AI provides the means for anyone to make art. Or does it? If AI might help anyone to produce creative works, can it be art?

As the cliched saying goes, art resides “in the eye of the beholder.” This expression indicates the peril involved trying to define art. We conventionally distinguish artful paintings from those that are not.

Some photographs are art while other photographs are simply snapshots. Sometimes dance is art and sometimes a dance is just a prom. Some stories qualify as art while others are simply narratives we share with each other. Anything one’s kid might do with fingerpaint is art but if it were made available for sale or displayed in a museum it might raise eyebrows. Why? Because art involves talent of a creative person who sees the world through a different lens, talent that transforms quotidian expressions into something unexpected, new. Special people make art.

Our society distinguishes Artists who possess something special from mere artisans who may make beautiful things but lack that something special, often dubbed a “spark of genius.”

These cultural norms provide a context where we assume that the artist’s creativity and originality inform the distinct talent that separates artwork from the artisanal.

While this special talent may be refined, popular culture discourses about artistic production often position it as something that is innate, something the artist is born with. From this special, somewhat vague something derives the cultural and perhaps more importantly monetary value of the works that artists produce.

When artificial intelligence creates art, it frustrates this set of assumptions. And it disturbs the cultural and economic relations that accompany it.

Artificial intelligence tends to conjure trepidation in the general public.

Poster for “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1964)

We fear its potential to replace or overpower us.

AI’s threat has occupied our cultural imagination for a long time, at least since von Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk. Think of mainstream films such as “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1964), “BladeRunner” (1982), Her (2013), “Ex Machina” (2015). Or television shows such as “Black Mirror” (2011-), “Person of Interest” (2011 – 2016), “Humans” (2015 – 2018) and “Westworld” (2016-).

Poster for “Person of Interest” (2011-2016)

These examples inform interpretations of AI’s more concrete work that forwards research into speech recognition (Siri), web search engines (Google), recommendation systems (Amazon, Netflix), and driverless cars (Google’s Self-Driving Car Project). When artificial intelligence enters the realm of art, we experience it as a sort of trespassing. The assumption is that AI does not belong.

Let’s put our anxieties into perspective: the root of “artificial” is “art.”

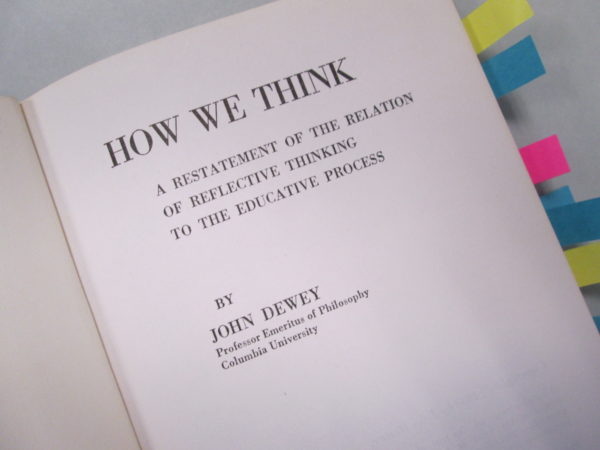

Early 20th century American pragmatist John Dewey addressed this relation in “How We Think” (1910). Dewey considers the nature and work of cognition and how we might better train ourselves and others to think well. The “idea of art” allows him to distinguish a kind of logic that is neither the formal logic of syllogism nor that of mathematical proof. He calls this third kind of logic “more vital and more practical” than the others (chapter 5). He describes this context-specific, “wide-awake, thorough, and careful reflection” as “artificial,” conceived as a practical art.

Dewey’s proposition may be less intuitive for early 21st century readers and those of the early 20th century.

For us, the “artificial” in artificial intelligence connotes not vital practical logic but simulation. As Dewey observes, his usage runs counter to those in which “artificial” “[suggests] the factitious and unreal,” the fake.

Our habits of thinking have accustomed us to imagine that art is not artificial, in the sense of fake or false. Rather, popular culture discourse figures art as unique and original. It is the expressive manifestation of creative impulse that even if not realistic expresses something true that reveals something uniquely human.

This is precisely the complication at work in the outcries against Allen’s award-winning artwork.

The debate points to some unquestioned habitual attitudes towards technology and the human.

We think our technologies are nothing more than tools to be deployed. In this scenario, AI serves as a technological implement like a paintbrush or a camera and nothing more.

But Allen’s picture evokes a different interpretation.

We mistake the software’s execution for the artist’s inspiration expressed in text commands. As a result, we imagine that AI has added creative elements of its own.

This situation catalyzes anxieties we observe in the public’s hostile response. But it also cracks open an opportunity to realign our thinking about art, technology, and artificial intelligence.

In “On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of Work in Progress” (1983), French poststructuralist Michel Foucault states, “What strikes me is the fact that, in our society, art has become something that is related only to objects … That art is something which is specialized or done by experts who are artists. But couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art?” (my emphasis).

Foucault shifts the terms from “art[work]” to “work of art.” He emphasizes process over product.

The process is our way of living. We practice this every day in how we use and mobilize our technologies for art or navigation. To return to Dewey, the “work” is the labor, the reflective thought imbedded in this practice. And this work can be art(ful).

To conclude: if we could focus on the how and not the what, then we might see something different in a painting such as Allen’s “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial.”

We might begin to think differently about our own engagements with technology. And we might approach technologies as our partners and not as our tools.

Heidi Rae Cooley is an associate professor in the School of Arts, Humanities and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. She is author of “Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era” (2014), which earned the 2015 Anne Friedberg Innovative Scholarship award from the Society of Cinema and Media Studies. She is a founding member and associate editor of Interactive Film and Media Journal.