One of my first childhood memories revolves around a flood.

I was an apple-cheeked pre-schooler, hair in a bowl cut, camping with my hippie-folkie parents at an old-time fiddlers’ convention in Ivydale, West Virginia. Hard rain brought flash floods, and the creek started to rise.

My memory of the event is a cold wash of grey-green. The damp olive smell of our Army tent. The brown water of what had been a creek hurtling past faster, wider, higher and higher till it finally began to whoosh over the bridge. My hand waving weakly to my father trapped on the other side. My mother’s face set in frantic worry. The eerie sound of constant music stopping. And then, everywhere, the mud.

If you’ve lived through it, if it separated your family and terrified you at the core, you never forget a flood.

At this point in November, you might have forgotten all about those floods in Central Appalachia in late July.This might even be a defensible forgetting, as the tide of climate disasters continues to roll in and the terrible truth of washed-away Kentucky children, gutted towns and hollers, ruined businesses, farms, and infrastructure gets overshadowed by other disasters on an unimaginable, probably unrepresentable scale even more criminally underrepresented than an invisibil-ized Appalachian disaster.

Fully a third of the entire nation of Pakistan in deluge? The island of Puerto Rico, powerless and underwater again, not even halfway recovered from Maria? Then Hurricane Ian smashed through Fort Myers Beach, Florida and took over every news channel with images of boats piled up like so many crumpled paper cups.

The national news still dwells on “After Ian” stories of elderly survivors facing an “uncertain future.” Ian left 126 victims in Florida alone — nearly three times the loss of life as in the Eastern Kentucky floods. Some of those who lost the most in Ian’s path were mobile home dwellers and Appalachian retirees. Two of the Florida deaths, according to the New York Times, were “men in their 70s who shot themselves after seeing the damage to their property.”

Meanwhile, in Appalachia, the devastation has been wrenching and the recovery work endless. However, the news and media coverage has become mostly local and regional. These features focus on fundraising efforts and GoFundMe pages, hashtags, and mutual aid efforts. A “Kentucky Rising” benefit concert in Lexington raises $2.5 million, while other efforts raffle kayaks, sew quilts for survivors, or campaign for “Housing First” for the 10,000 who lost homes. One Appalachian Regional Healthcare CEO reported that 172 of her own employees “lost everything in the flooding this summer.” In the face of such total devastation, local solutions can only be piecemeal.

Appalachia and the Media

The media has a habit of remembering and forgetting the Appalachian region.

By the time Lyndon B. Johnson made eastern Kentucky the poster child for his War on Poverty in 1964, Appalachia was already a fraught media object, the television tropes almost exactly as old as the medium broadcasting them.

By 1960, some 90% of American homes had plugged in a TV. By 1962, they could already tune in to “The Beverly Hillbillies” (1962-1971). Unlike documentary newsreel images of Appalachia that reassured middle-class viewers that white poverty would remain someplace over there, the Clampetts troubled that ground with culture-clash every week around their Beverly Hills “cee-ment pond.” Since then, the pendulum has continued to swing, most frequently between laughter from the Clampetts to “The Simpsons’” (1989-present) Cletus the Slack-Jawed Yokel and loathing from “Deliverance” (1972) to “Orange is the New Black’s” (2013-2019) Pennsatucky.

An equal opportunity media target, Appalachia is wide enough to take hits from left, right, and center.

The evocation of love or pity has been more rare, though it’s not surprising that Dolly Parton’s latest television production is called “Heartstrings” (2019). The better part of her career has been spent trying to make people feel something about Appalachian lives. If not identification, she demands at least a recognition of her people, from Jolene to the girl in that “Coat of Many Colors” to the hundreds of Tennesseans who lost their homes to wildfires that raced into Sevier County from the Great Smokies.

Identification is critical to social justice and social change. But when representations of Appalachia whip between scapegoating and erasure, the connection fails and justice is derailed.

In the late 1960s, President Johnson remembered Appalachia for its poverty, but the miner strikes of the 1970s are forgotten.

In the 1980s-’90s, union-busting “friends of coal” pitted workers against environmentalists, while regional pork-barrel politics made the headlines.

After 2016, pundits located Trumpism in Appalachia, but forgot about mountaintop removal coal mining.

The dramatic Dollywood fires in East Tennessee registered, but the slower violence of the oxycontin overdose crisis? Less so.

Ohio Senator-elect J.D. Vance and his “Hillbilly Elegy” (2020) have made their mark, but few know that West Virginia has the highest number per capita of trans-identified youth in the country.

In the case of the July 2022 Central Appalachian floods, this pattern of forgetting hits particularly hard. This time, it seems not only cruel, but downright dangerous.

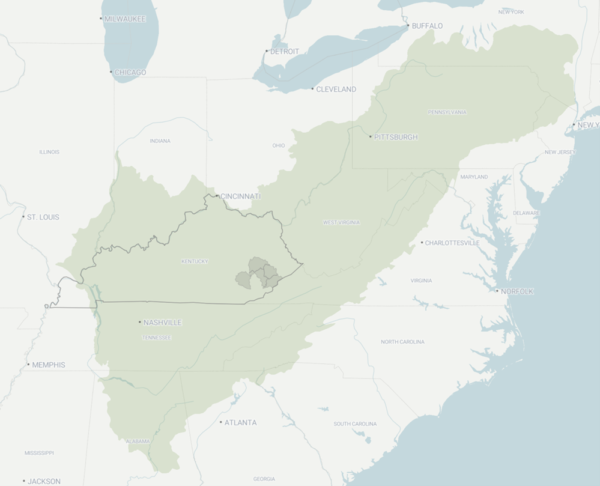

Eastern Kentucky Counties most affected by the 2022 floods: Letcher, Knott, Perry, Breathitt, Owsley, Clay.

What makes a loss catastrophic? Loss of life? Livelihood? Property? Community?

Forty-three lives were lost in the 2022 Central Appalachia Floods.

One-hundred-forty is the total official death toll from Hurricane Ian.

The Pakistan floods killed over 1,700.

Hurricane Maria, five years ago in Puerto Rico? 3,000.

Hurricane Katrina, 1,833.

No matter the measure, Appalachia will never win in the war of grim statistics. Population density is lower. Poor property values and high poverty levels mean that the pricetag — the way people prefer to comprehend disaster under capitalism — is always less.

How do we measure devastation?

Hindman Appalachian Writers’ Workshop

I was supposed to be there.

It was supposed to be me racing through the night, sloshing through water rising over my ankles, my knees, then chest deep. It was supposed to be my rental car that got swept up and washed away down Troublesome Creek.

I had applied to and been accepted for the Hindman Appalachian Writers’ Workshop, a longstanding program supporting Appalachian writers and writing, hosted on the campus of the Hindman Settlement School. Hindman is a local treasure, the first Progressive era settlement school of its kind in the country established in 1902 with a mission of Appalachian uplift through education and opportunity.

It would have been my first time at the Workshop. That week of writing in Appalachia was going to jumpstart my collection of essays about Appalachia with the benefit of feedback from an array of celebrated writers like Meredith McCarroll, Carter Sickels, and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon. There would have been readings and workshops by luminaries like George Ella Lyon, Silas House, and the headliner Beth Macy, author of “Dopesick” (2018).

I would stay in the dorms and work in buildings named after life-saving doctors like Dr. Joseph Stuckey, who helped eradicate trachoma in the region, or hall-of-fame writer-heroes like James Still, who spent most of his life at Hindman. There would be the legendary hangouts in hot late July evenings, and music, and community, and a commitment to keeping writing, poetry, songs flowing into and out of the region.

But at the last minute, a conflict in the family schedule meant I had to withdraw.

“I’ll reapply next year,” I told myself. “Just keep my deposit,” I told the director, “to support the good work you folks do there at Hindman.”

In the days following news of the floods, I was sick with anxiety.

I scrolled through Facebook looking for details. I texted friends with aging parents in Pike County, “Thank you – everyone is okay…. Mom and Dad live on a hill….”

As the extent of the damage came into focus, I looked for places to donate. I scoured the news coverage, trying to understand where, how, why this had happened. I scoured my soul trying to understand why I had been spared.

Appalachian Means of Production

The first image etched in my mind from the Central Appalachia floods was the one I opened with, of the Appalshop building with its entire first floor under water.

Founded in Whitesburg, Kentucky, in 1969 with funds from those War on Poverty programs, Appalshop operates a radio station, theatre, public art gallery, record label, filmmaking institute, and an array of other justice and development initiatives including programs for incarcerated people and a youth documentary film workshop that had just ended the week before the floods.

The North Fork of the Kentucky River typically trickles past Appalshop at a depth of 2-3 feet. This time, the floods raised the river to 20 feet, more than 6 feet higher than the last record flood in 1957, outside most folks’ living memory.

The damage was “catastrophic” to Appalshop’s archive, theater, radio station, and the Boone Building which houses their Appalachian Media Institute. The losses have been devastating both materially and emotionally.

In what “feels like a miracle” according to the Appalachian Media Institute’s director, two of the three Summer Documentary students’ films were saved after the hard drives were recovered from equipment otherwise damaged “beyond repair.” Archivists and volunteers continue their tireless efforts to save irreplaceable pieces of a complex archive at both Appalshop and at Hindman, where innumerable books, records, slides, photographs, and other artifacts have either been lost, dashed into freezers to await restoration, or hung out to dry.

The Central Appalachian floods may have hit relatively small, relatively isolated communities with relatively small populations, but they attacked some of the most vital organs of Appalachian culture: Appalshop in Whitesburg, and in Hindman, the Settlement School as well as an Artisan Center housing a beloved center for luthiery, an Appalachian Dulcimer Museum, and more.

Kentucky writer and bookshop owner Mandy Sheffel who was at the Hindman workshop the week of the floods puts it best: Appalshop and Hindman are “two of our most sacred spaces.”

Cleanup efforts at the luthiery center continue where “countless” dulcimers were pulled out the windows and down Troublesome Creek.

Even in the face of the desperate losses of children, livelihoods, businesses, cars, houses, and infrastructure, what makes these floods most catastrophic to me is the damage to these cultural institutions, these hard-won Appalachian worker-controlled means of production.

Like Hindman, Appalshop tells Appalachia’s stories. Through its 50-year history, its reach has been long. We need these engines to generate representations of the region that make sense, that hold up, that ring true. These places are the pen and ink, the camera and film, the instruments, microphones, reels of tape that for decades have been doing the critical and ongoing work of making Appalachia visible and audible.

First the floods devastated these institutions that reliably tell Appalachia’s stories, then the conventional media forgot about the floods. It was a one-two punch. I fear the obliteration that may result.

How can people identify with an Appalachia no one can see? If a culture falls in the woods and no one is there to record it, does it make a sound?

One Knott County effort collected 600 new and refurbished donated instruments from across the country to deliver free to mountain musicians from the flooded region.

Media coverage of the deaths of four young siblings or the ruin of a Black-owned grocery in a food desert rends the heart, but the damage to these cultural institutions stops my blood.

Unlike a precious life or treasured home, places like Appalshop and Hindman are not merely corporeal, material, or spatial. They are metaphysical and ontological. They manifest Appalachia and they tell time. In their archives, they have preserved the region’s past. With their workshops, classes, programs, and fellowships, they have articulated its present, and envisioned its future.

Meanwhile, the data analysts keep trying to wild-guess about the next 90-year flood. They sell that data as the floods just keep on coming in this new era of disaster-capitalism and eco-grief.

Climate Grief

We use the language of water to talk about memory. It floods in, rushes back, washes over us.

We use the language of water to talk about grief. It comes in waves, we drown in tears, or drown our sorrows.

Climate grief is now a diagnosis.

Another image etched into my mind from the Central Appalachian floods is of Tessa Fugate-Caudill, a tattooed Letcher County librarian in a tank top, leaning on the handle of a shovel, up to her armpits in mud and surrounded by puddles and piles of ruined books. Despair fills her eyes, caught on the verge of something worse than tears.

“These Kentuckians will never ask, but they desperately need cleaning supplies, building materials, books and much more, so I am asking for them,” says bestselling local author Kim Michele Richardson who has raised some $30K to help Letcher County librarians like Fugate-Caudill restore their collections.

Richardson’s comment gives sad testimony to a widespread bootstrap mentality that threatens to leave each to his own in a place where few had much to begin with. “I actually believe that, whenever possible, we should pull ourselves up by our bootstraps,” Kentucky Democratic state Rep. Angie Hatton said in August. “But our bootstraps just washed down the creek. Can’t even find them right now.”

Hardly anyone in these communities has flood insurance. Some estimates are that only 1-2% of residents have any. Some don’t even carry homeowner’s insurance. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood maps are notoriously inaccurate in identifying risk in the region or disregard flash flood zones altogether.

Appalachia, the place I still call home, bears the burden of a “trifecta” of forces that make climate-related disasters feel more apocalyptic than catastrophic.

Already an uneven ground of steep hills and low hollers, Appalachia disproportionately bears the regular torrential rains of global warming which cannot be absorbed by stripped and scarred soils compacted by an extractive fossil fuel industry. That longstanding exploitation has left much of the region without the economic resources necessary to fully recover or to adapt.

But in the face of neoliberal attitudes, historical wounds, and structural inequalities, a developing culture of mutual aid and an emergent politics of disaster justice offers hope.

Tessa Fugate-Caudill, cleaning up her library in Letcher County, Ky. Photo by Allan Detrich. Used with permission.

Belatedly, I have been reading “Fahrenheit 451” (Ray Bradbury, 1953) for a class I’m teaching in the spring. In Bradbury’s dystopia, books are outlawed to maintain social control, and wherever they are discovered, the ironically-named Firemen race in, throw the books into huge piles, and incinerate them. I am reminded uncannily of the mounds of muddy books next to that Eastern Kentucky librarian. They’re not the same thing, I tell myself. Or are they?

The word natural obscures the politics, architecture, and design behind any media-termed disaster.

The people most impacted by the Appalachian floods are targeted people. Their often meagre and hard-won resources are made disposable by ideological frames that call it bad luck when such violence afflicts the already vulnerable.

There are patterns.

This isn’t the first commercial-media-dubbed “unprecedented” flood disaster. Only days ago, Mitch McConnell announced Kentucky would receive an additional $49 million in Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants to help recovery from last year’s disasters: the western Kentucky tornadoes in December and “historic” Eastern Ky flooding in March and April of 2021.

With names like Troublesome Creek and Hazard County, Appalachia is a space where the dangers of the environment are already inscribed. But there is nothing “natural” about these floods.

Appalachia is the canary in the coal mine of a climate crisis.

The people who live there are targets. Their libraries and cultural institutions are blast zones.

In Appalachia, the books, the dulcimers, the films, songs, and poems have always been the region’s most powerful weapons and not simply because knowledge is power.

They matter most because Appalachian cultural production has been the strongest levee against Appalachian dehumanization.

Anna Creadick teaches English and American Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, NY. Author of “Perfectly Average: The Pursuit of Normality in Postwar America,” she has written essays about 20th-Century U.S. literature and culture for Southern Cultures, Legacy, Mosaic, Appalachian Journal, and other publications. She divides her time between the Finger Lakes region of New York and the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina.

To Do More:

Hindman: https://hindman.org/about/

Appalachian Writer’s Workshop: https://hindman.org/workshop/

Flood Relief: https://hindman.org/donate/

Appalshop: https://appalshop.org/

Appalachian Media Institute: https://www.amiappalshop.org/

Donate: https://appalshop.salsalabs.org/AppalshopGeneralGiving/index.html

Appalachian Artisan Center: https://www.artisancenter.net/

Appalachian School of Luthiery: https://www.appalachianluthiery.org/

Donate: https://www.gofundme.com/f/aac-flood-relief-fund-hindman-ky

Donate to Library Relief: https://www.kimmichelerichardson.com/eastern-ky-flood-relief-for-libraries

To Learn More:

A necessary corrective: Elizabeth Catte, “What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia”

A Blog to keep up with Appalachia: 100 Days in Appalachia

On the cleanup: Silas House, “Pulled from the Flood”

On victim-blaming and over-policing, on top of everything else: Tarence Ray, “Flooding in the Sacrifice Zone”

On Hindman: Appalachian Journal, “‘It’s Not a Job To Me’: Mike Mullins and the Hindman Settlement School”

On Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: Nicole Greenfield, “Mutual Aid and Disaster Justice: ‘We Keep Us Safe’”