The day: Monday, February 27, 2023.

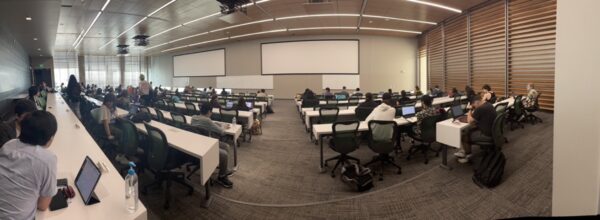

The place: A large lecture class in the new Engineering and Computer Science West building at the University of Texas-Dallas. It’s a wide space, accommodating 300 students. Great windows and elegant wood window treatments allow for a lot of light. Raked seating — semi-flexible.

Panorama photograph of ECSW 1.315, University of Texas at Dallas

The course: Introduction to TechnoCulture (ATCM 2300).

The incident: A student outburst.

The lecture meeting started as it does every week. Students opened their “smart” devices — laptops, tablets, phones — to take the week’s quiz.

Switching Gears

Instead of our weekly conversational lecture, I switched gears a bit to address expectations for the upcoming midterm assessment.

A student who sits in the very back of the lecture space raises his hand. He has participated in discussion before. In the moment, I am neither surprised nor worried.

But instead of a testing proposition or a skeptical question, the student lashes out. The outburst is like nothing I’ve experienced before — and I’ve taught large lecture courses for over a decade.

The particular course is a required introductory studies course for the undergraduate major.

Those of us who teach the course hope to encourage students to think more critically about how they engage and understand their technologies. We want them to account for how technologies shape culture. We want them to account for how culture and related social protocols inform the design, development, dissemination and use and disposal of technologies.

Introduction to TechnoCulture has a goal to cultivate a sense of responsibility as students engage technological practices as thinkers, makers, and members of a broader public. Active and vocal student engagement is supported in the space.

Thrown Away

From the student’s perspective, the course is out-of-date. In attending to books and cameras, the phonograph and subsequent audio technologies, he contends we have failed to consider the one technology that will replace everyone: Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Image from “As AI Advances, Will Human Workers Disappear?” in Forbes (2022)

From this student’s perspective, we — professor, teaching assistants, and students alike — are at risk. We all will be “thrown-away.” The student stands and reiterates this point more adamantly: We will be thrown away!

I recognize from the student’s impassioned statement that he is frustrated.

By this time in the exchange, I am concerned. I feel my pulse rate increasing. I’m sure my gestures and movement in the lecture space are becoming differently animated. I have not moved up the steps into the raked seating that defines how students have access to the lecture and its material. I usually move up and down the aisles.

The syllabus does indicate that AI will be a forthcoming topic in the last four weeks of the semester. In his agitation, the student seems to have forgotten this fact.

The student overlooks what the course has emphasized since day one: the continued relevance of older technologies, which continue to shape culture and inform how persons and populations behave in society. For example, how early photographic practices facilitate better interpretation of continual surveillance in facial recognition, Instagram, and the selfie that disseminate our data to corporate and governmental entities.

Taking a step back, thinking-through

Risk discourse permeates academia, with terms like “risk assessment,” “risk management,” and more. We’re all assessed against various risk measurements. The ideas of Michel Foucault on power and control seem especially pertinent now, where his theories transform into practice.

The student’s concern does not engage any kind of theoretical or abstract thinking about risk analysis. And why should it, really? For him, the risk is immanent, material, and consequential.

Risk storms around us everywhere

Other students attempt to quell this student’s anxiety.

One suggests that AI is not all that smart. Another student suggests we might remember from previous examples that new technologies do not automatically eliminate jobs. Sometimes, they allow us to imagine different ones. I hear a desire to reshape the narrative of risk associated with the emergence of new technologies.

Social robots: MIT’s Kismet (late 1990s)

Where do we meet the students?

Our higher education institutions promise a commitment to prepare students to enter the workforce so that they might contribute their labor to society in meaningful ways. As professors, we also want our students to find employment that respects their expertise and fairly compensates them.

We do so not simply to train students to think beyond particular disciplinary fields. We assist them to imagine that their labor might matter more than the next quiz or midterm paper.

We need to encourage students to think about technologies in critical and creative ways. I want the students I teach to engage the expectation that technologies invite curiosity and prompt a desire to entertain thorny, complex questions.

What do AI and AI apps do to help us explore meaning-making as humans?

How does AI inform how we encounter new experiences?

Might AI be a means for thinking through how we better learn to express ourselves to each other and how we respond to the world around us?

Image from “The drive towards ethical AI and responsible robots has begun” in Phys.org (2015)

Concluding Reflections

In ruminating about this incident, I suspect the student’s contentions about what is missing in the course actually express fears of change, of the unknown and/or the unresolved, of the messy, and yes, of the incomprehensible. These fears form the undercurrent of our lives right now.

The disruptions and questions that AI provokes require us to learn to think in new ways.

Yet our old fears and concerns about how we each make our way in the world also remain.

Understanding how to make sense of the new and the incomprehensible alongside the continuing contradictions of anguish and hope hover as the most intense challenges of our current moment.

Heidi Rae Cooley is an associate professor in the School of Arts, Humanities and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. She is author of “Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era” (2014), which earned the 2015 Anne Friedberg Innovative Scholarship award from the Society of Cinema and Media Studies. She is a founding member and associate editor of Interactive Film and Media Journal and co-director of the Public Interactives Research Lab (PIRL).

Header image from “What an Artificial Intelligence Researcher Fears about AI” in Scientific American (2017).