On September 22, the Park Center for Independent Media hosted a discussion with dissident writers who were forced from their homelands and found sanctuary through a City of Asylum in Ithaca, Pittsburgh, or Detroit. The event, which was attended by nearly 70 Ithaca College students, faculty and community members, provided an opportunity for these writers to read from and discuss their work, and explain why their writings put them in danger in their respective countries of origin.

The discussion was led by PCIM Director Raza Rumi, a former writer in residence hosted by the Ithaca City of Asylum. “This event was exclusively put together for our brilliant students to hear from this panel and learn the important lessons of not giving up and upholding truth.”

Rumi mentioned how dissent was being muzzled globally, “from Middle East to Africa and from Latin America to the Northern Hemisphere” by populist and fascist leaders.

Anouar Rahmani, a poet and novelist, who publicly called for legal same-sex marriage in Algeria in 2015 and was threatened with imprisonment for writing about human rights opened the discussion:

“I didn’t want to be novelist actually. It all happened as a coincidence. In 2015, a lot of my friends who were Atheist or Christian and they were actually in jail because the regime, or the Algerian government at the time, decided to use religion as a way to legitimate their power.”

“I didn’t want to be novelist actually. It all happened as a coincidence. In 2015, a lot of my friends who were Atheist or Christian and they were actually in jail because the regime, or the Algerian government at the time, decided to use religion as a way to legitimate their power.”

He added that when he wrote his first novel, he merely wanted to express himself. But his work created “a big buzz and everyone on the internet started to speak on the novel… And the police decided to interrogate me,” he said.

Political cartoonist Pedro X. Molina fled Nicaragua during a crackdown on dissent and news media in 2018, in which state forces jailed many of his colleagues and occupied his newspaper’s offices. Molina explained that the extreme level of censorship recently reached new height: CNN had recently been banned in Nicaragua the night prior, and Molina shared a preview of his cartoon criticizing the ban.

Molina showed some of his cartoons, which lampooned the ruling party and brought attention to those who have suffered or were killed as a result of the authoritarian suppression of dissent. Molina described the plight as an artist living under an oppressive regime.

“I stopped worrying about my role as a cartoonist, having people laugh, and I started to worry more about connecting with people. And I found out that the best way that I could connect with the people, it was to realize that I was just one of them; the only difference between them and me is that I could draw and I could actually have a voice when they can’t. Then it became your responsibility; you had the chance to say something, so you better do it because there are thousands of people who can’t.”

“I stopped worrying about my role as a cartoonist, having people laugh, and I started to worry more about connecting with people. And I found out that the best way that I could connect with the people, it was to realize that I was just one of them; the only difference between them and me is that I could draw and I could actually have a voice when they can’t. Then it became your responsibility; you had the chance to say something, so you better do it because there are thousands of people who can’t.”

Pwaangulongii Dauod, a Nigerian novelist, essayist, and memoirist, gained national recognition for his 2016 essay, “Africa’s Future Has No Space for Stupid Black Men.” The essay also provoked threats to his life which resulted in his fleeing to the United States in January.

Dauod expressed his dissatisfaction with Western coverage of African issues and stories. Recalling how he would give tours to American journalists he said, “The next week I would go on to read what the New York Times has published and it’s a different experience. And you kind of sense that [this journalist] is not trying to be dishonest but he can’t do more than … I don’t know how to put this in English. But that is why Al Jazeera has come to stay in countries like Nigeria. So Al Jazeera will recruit a Nigerian journalist to report a Nigerian story, or will send a white journalist to Nigeria to work with a local journalists to write the stories together. And that brings more nuance, credibility, and the emotion to the reports.”

Dauod added that the international coverage of Nigerian issues was often disconnected from the Nigerian experience.

“From outlets like New York Times, CNN, they produce top-quality journalism, but something is missing. It’s good language, good reporting, but it’s not reflective… there’s something missing that someone with a foot on ground would know.”

Molina filled in, “It’s the human connection.”

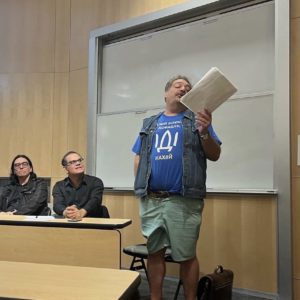

Dmitry Bykov is one of Russia’s best-known public intellectuals, having authored more than 70 books, including novels, poetry, biographies, and literary criticism. His work, which was often critical of the Russian state resulted in his being banned from teaching or appearing on Russian TV. In 2019, he spent five days in a coma after falling ill during a speaking tour.

An independent investigation blamed Russian security forces for poisoning him with the nerve agent Novichok – the same that was later used on Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in 2020.

Bykov delivered an animated standing delivery of his poem, “A Ballad of No Laments,” first in Russian, then in English, adapted to retain its rhyming scheme because, as Bykov said, he is “old-fashioned” and insists on rhyming verses.

A Senior Ithaca College student from Russia asked Bykov how much he believes it will it take for Russia people to push back against Putin. Bykov responded, claiming, “Revolt and rebellion isn’t Russian way. That’s something Ukrainian. In Russia, the population consists of the most free slaves. They are slaves because they have no political opposition to power. We are free because we have freedom of speech in Russia, sure. We can criticize anything at all… We are free in everything except criticizing Putin. And maybe this is the real corruption of national spirit because the people are maybe equally indifferent to any idea – liberal or totalitarian; Russia is not an ideological country.”

A Senior Ithaca College student from Russia asked Bykov how much he believes it will it take for Russia people to push back against Putin. Bykov responded, claiming, “Revolt and rebellion isn’t Russian way. That’s something Ukrainian. In Russia, the population consists of the most free slaves. They are slaves because they have no political opposition to power. We are free because we have freedom of speech in Russia, sure. We can criticize anything at all… We are free in everything except criticizing Putin. And maybe this is the real corruption of national spirit because the people are maybe equally indifferent to any idea – liberal or totalitarian; Russia is not an ideological country.”

Responding to a question from a student about how the writers’ attitudes toward their home countries have changed since encountering retribution for their dissidence and subsequently leaving their homes, Bykov said:

“I must say that to be a dissident, it is very shameful… to be a person who betrayed his mother, his country. Dissidence is the kind of shameful disease… to know that you’re their enemy. I love my motherland. This angry bloody monster that attacks Ukraine isn’t my mother land.”

Rahmani, who has faced both legal and personal harassment for his advocacy for individual freedom, environmental rights, and the rights of minorities, women, and LGBTQ+ people, expressed his feelings about Algerian society. “I never hated those people who spit on me or threw stones at me, because, actually, they never hated me. They just didn’t know how to love.”