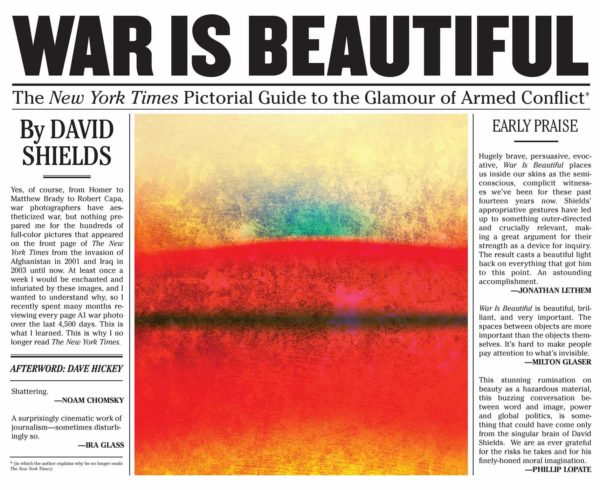

Wars are ubiquitous in the everyday lives of people who imagine themselves living in peace. Yet, it is easy not to see them — to acknowledge neighbors as veterans, recognize war widows in their role as caregivers, interpret war monuments as celebrations of violence, view high-tech innovators as war perpetrators, perceive students as enlisted soldiers. It is even easier not to see wars when happening elsewhere, even if they are constantly in the news. David Shields’ careful analysis of The New York Times’ front-page photographs of the U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrated that the images were selected to go well with morning coffee; wars are made to be beautiful, especially when frequently served with breakfast.

“War Is Beautiful,” David Shields (2015)

I have been watching wars for decades now — Somalia, the former Yugoslavia, Burundi, Rwanda, Congo, East Timor, Chechnya, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Myanmar, Yemen, Georgia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Ukraine … I think of Cyprus, Northern Ireland, Israel and Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq and Iran … the list is long and the wars are all connected — by movements of soldiers and mercenaries, training manuals, arms traffickers, refugee flows, illicit trade, webs of violence linking gendered and racialized domestic abuse and terror attacks with distant battlefields. What I have learned in these years of following wars and their trail is that the more we watch wars, the less we might be able to see them.

All War Images Are Staged

Filmmaker Errol Morris suggests that one of the reasons why we watch wars without seeing them is because all images of war are staged. Not fake — staged. We tend to argue endlessly over reality and propaganda of war visuals while still treating them as documentary evidence — whereas, in fact, what we can ever see is only a sliver of a (war’s) story. We substitute seeing for believing; what is visible in the frame for the event itself. Instead, we should be looking beyond the frame, envisioning that what we cannot see, considering what was cropped. As Morris puts it, we must wonder: isn’t there always an elephant, just at the edge of the photograph?

Ubiquitous wars have generated their own repertoire of images: children’s faces pressed against foggy windows, old women on empty roads with burnt down buildings behind them, weary or hyper-charged soldiers standing by piles of armaments, grieving women by gravesites or photographs of lost family members, fleeing people crowding busses, trains, or refugee camps. Wars and their images bleed into each other, normalizing violence as much as justifications for killing do — dictators, democracies, weapons of mass destruction, freedom, sovereignty, terrorists, rapists, Nazi sympathizers. Wars bleed into each other yet appear localized, unique to their own place and time: we do not see jets bombing Aleppo flying over Ukraine, or the drones from Afghanistan arriving in Yemen.

Looking Beyond the Frame

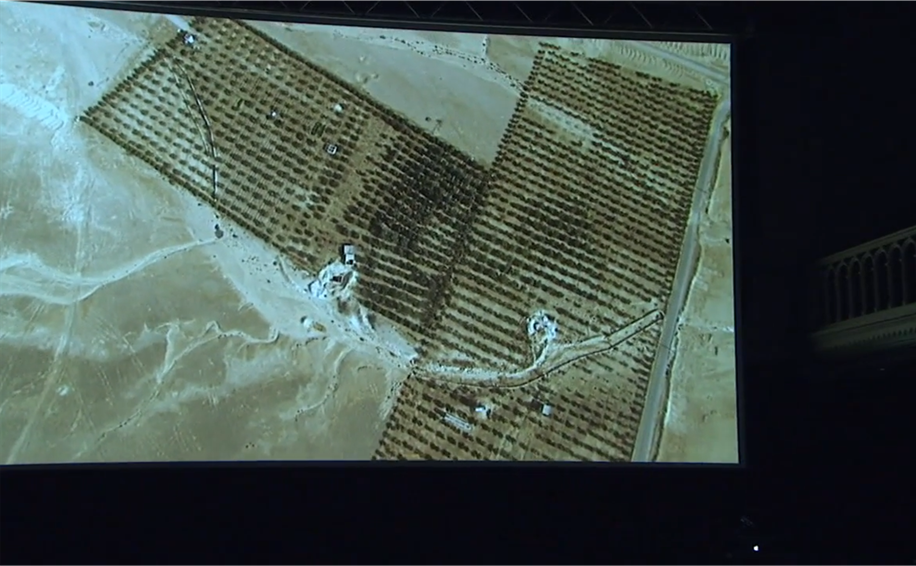

To see wars, we must look sideways, elsewhere, outside of the frame. Jananne Al-Ani, a visual artist born in Iraq who works and lives in the U.K., has created a series of works called “Shadow Sites” — images of historical settlements in the Middle East, intended to counter the now common aerial views from war planes which consistently display Middle Eastern terrain as an unoccupied, available desert. Al-Ani’s interest in landscapes and their relation to bodies in war was in part inspired by the work of an archeologist, Margaret Cox, who described her search for mass graves in Kosovo as being driven by blue butterflies. The butterflies feed exclusively on the wild flower Artemisia Vulgaris, which grows upon dead bodies. To see a grave, one must follow a butterfly.

“Shadow Sites II,” Jananne Al-Ani (2011)

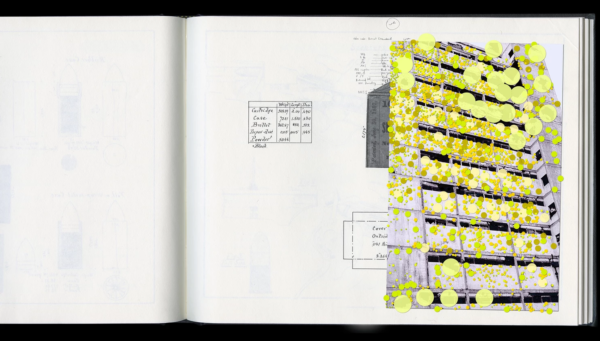

Walid Raad, a U.S.-based artist, who was 8 years old at the time of the Lebanese civil war, centers his artwork around objects and images collected during the war — shrapnel, bullets, documentary photographs of their location. He has designed a system which matches the weapons with their manufacturers and the photographs are dotted with differently colored marks for Saudi Arabia, China, U.S., Switzerland, NATO, U.K. and Israel, Belgium, Egypt, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iraq, Italy, Libya, Romania, Venezuela … Raad’s collection is a part of a collective effort to create a record of the Lebanese civil war. Except, the foundation that he works for and with — the Atlas Group — is fictional. As the curators of his exhibit at the National Gallery of Canada wrote: Raad’s artwork, “Let’s Be Honest, the Weather Helped,” which blends reality and fiction, “may not picture the adolescent project of collection it claims to; rather, it suggests a history of proxy war, Western intervention, and the reaches of the global arms trade. The deception is quite productive.”

Or consider an exhibit by Bosnian artist Šejla Kamerić at the seat of Fondazione Adolfo Pini held in the winter of 2018-2019. In this elegant 18th century palace on Corso Garibaldi in Milan, Kamerić staged an animation called “Sunset.” It was based on what is believed to be the only color photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising in 1943 and seemed to extend smoke and flames beyond the screen of the monitor. Next to it, stone spheres, reminiscent of cannonballs and engraved with grid coordinates of mass graves in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Bosnia, are set on a shiny parquet floor, their numbers multiplied by antique mirrors. Photographs of explosions adorned delicate wall arches above period furniture and fireplaces. The exhibit was entitled “SUMMERISNOTOVER” — a nod to a season when violence often escalates in war times but also to a media cycle when atrocities can take center stage as other news subsides. And in the background of the carefully chosen title — a longing for never-ending summer vacations and nostalgia for what might not have ever been or will come again: peace.

Follow the Butterflies

Ever since February 24 and the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I have been bracing myself for another war — of images, propaganda, and misinformation. And I have made a deliberate decision not to watch the war in Ukraine but to see it — by looking sideways, elsewhere, outside of the frame. That entails considering this war side by side with all the others that we have witnessed since the end of the Cold War. It also entails considering what cannot be represented within a frame of any war image: patterns of organized violence, emotional void, humiliation, the stench of burned flesh, denials of guilt and complicity, betrayals by friends, and escapes of families. I think of refugees gathering at train stations exchanging news and packages. I imagine looted homes and soldiers drunk on violence. I see women picking up pieces of life after death. I wonder how long it will take for the survivors to tell their stories, to speak again.

“Let’s Be Honest, the Weather Helped,” Walid Raad (1998)

Every day, I witness another Twitter storm among friends and colleagues over Russian or American imperialism and their respective hypocrisies. In their arguments, they (re)constitute hierarchies of victimhood and foreign wars. The war is a tool for debate and promotion of academic theories. There are recurring discussions about off-ramps for Russia, rearmament, tactical moves by either army. The maps of Ukraine are redrawn with different proposals for partition, as if the terrain is — much like in the Middle East — an unoccupied, available desert. And the images from the war, as Morris would predict, are treated as evidence, as if the only question is whether they are real or fake, propaganda or document.

But this war is not about Zelensky and a photoshoot in Vogue. There is an elephant at the edge of the frame:

there are blue butterflies feeding on mass graves

differently colored bullets edged in collapsed buildings

smoke and cannonballs filling beautiful European palaces.

Wars should not be watched by people who imagine themselves living in peace.

Wars ought to be seen.

Aida A. Hozic is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Associate Chair of the Department of Political Science. Her research is situated at the intersection of political economy, cultural studies, and international security. She is the author of “Hollyworld: Space, Power and Fantasy in the American Economy” (Cornell University Press, 2002), and co-editor (with Jacqui True) of “Scandalous Economics: Gender and Politics of Financial Crises” (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Header image screenshot: “Shadow Sites,” Jananne Al-Ani