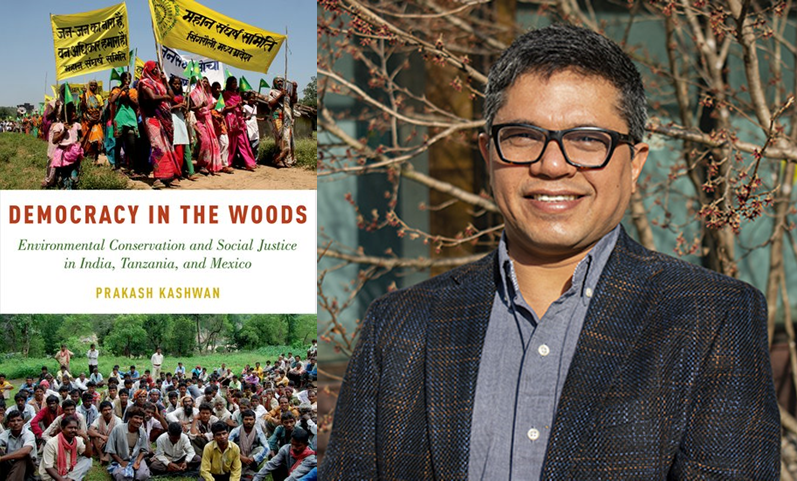

On Tuesday, October 26, Dr. Prakash Kashwan joined Ithaca College professor Dr. Jake Brenner for a discussion on environmental justice, interdisciplinary scholarship, and the legacy of colonialism in conservation. Dr. Kashwan is an environmental justice scholar-activist and a professor of political science at the University of Connecticut, Storrs.

PCIM Director Raza Rumi introduced the evening’s conversation, citing alarming figures from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) August report. Rumi’s summary illustrated humanity’s immense warming of the planet and highlighted media’s tendency to obscure how the climate emergency exacerbates natural disasters and causes adverse impacts on immigration, health, world economy, and global patterns of equality.

Dr. Kashwan explained the various fields he teaches and engages with in scholarship, including human rights, environmental justice, south Asia in world politics, climate justice, and forest and water conservation. Dr. Brenner asked him to elaborate on his scholarship method of “workshopping,” which can pertain to research in any of these fields. Just as carpenters make pieces of furniture to fit the relevant context and use an array tools to craft them, “good scholarship should be like workshop: address the particular context in which a question is being asked, then … combine different methodological and theoretical frameworks to address problems.”

Furthering the issue of interdisciplinary research, Dr. Brenner wondered, “How can we forge science collaborations to promote social justice outcomes?” Dr. Kashwan named a hypothetical research project combining ecology and social science to emphasize that “the best interdisciplinary scholarship happens when people trained in complimentary disciplines work together.” In this instance, environmental science students and researchers should always consider how the problem at hand relates to our real-world challenges.

Considering real-world impacts remained a point of emphasis during their talk. Dr. Brenner cited a quote from Dr. Kashwan’s article in Environment magazine asserting that “the effects of colonialism and racism are etched into the dominant philosophy, models, and institutional apparatus of global conservation.” In terms of “literal history,” Kashwan explained that “today’s global conservation emerged during colonial times, when the prevailing wisdom and ‘consensus’ was that poor people in Africa and Asia were too ignorant and illiterate to care about the environment. So, white men, colonial administrators and scientists, needed to conserve wildlife, biodiversity, and other natural resources to protect them from hungry and ignorant people.”

Dr. Kashwan further detailed that “The entire institutional structure, the systems for promoting global conservation, were meant to exclude local people from national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. We call this the fines, fences, and firearms approach,” since fences were built to keep locals off designated land, with severe fees and sometimes shoot-to-kill orders punishing those who crossed them. “This is not a metaphorical reference; there have been actual shootings in Africa and Asia.” In India, 25 people were killed in 5 years to protect rhinos. But rhino hunters carry rifles, “so you can’t shoot the real poachers — you can only shoot poor people.”

The conversation interrogated the production of knowledge, particularly pertaining to the relationship between researchers and local people. Dr. Brenner described how imbalanced power dynamics perpetuates inequality and injustice, and Dr. Kashwan delved into the issue of expertise and appropriation. The history of environmental science is populated by white men who hired locals, usually with an understanding of regional ecology, as laborers, only to name species after themselves without acknowledging or compensating local communities. As part of undoing this legacy, Kashwan stated that researchers should explicitly acknowledge local people, and ensure they gain the benefits of studies.

To close the evening’s discussion, Dr. Kashwan encouraged doing away with the false binary between nature and society — reintegrating these concepts into one should shift our perspectives and consumption habits to decolonize notions of land ownership and allow biodiversity to flourish everywhere. The maintenance of manicured lawns, for instance, smothers natural conservation and generates considerable fossil fuel emissions.