The Andy Warhol Foundation has lost its suit against photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

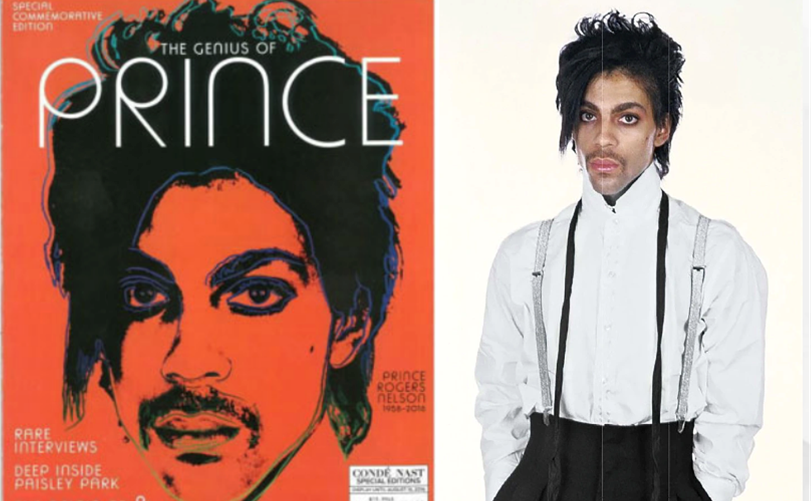

The Supreme Court’s May 18, 2023, ruling positioned the decision as a defense of lesser known artists against famous ones. The majority argued that Fair Use was not applicable when Warhol’s “Orange Prince” appeared on the cover of Condé Nast to commemorate Prince in 2016.

The court insists that this narrowly circumscribed decision only applies to this particular use of “Orange Prince” despite numerous headlines suggesting otherwise.

However, my concern as an art historian, not a copyright lawyer, is that calling this framing narrow represents a lack of understanding about the place of capitalism in the art world today.

The Case

The origins of Warhol’s Prince Series are blatantly commercial.

In 1984, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to transform a photograph of the emerging artist Prince. They paid Lynn Goldsmith $400 dollars to use her 1981 photograph one time. The magazine published “Purple Prince,” crediting both Warhol and Goldsmith.

After Prince’s death in 2016, Condé Nast, Vanity Fair’s parent company, approached the Warhol Estate to license “Purple Prince” again. They learned that Warhol had created an entire Prince Series and paid the estate $10,000 to license “Orange Prince” for their magazine cover.

They did not approach Goldsmith.

Goldsmith learned of the larger series after seeing the 2016 publication and recognizing her image. She sought compensation from the Warhol Foundation. They sued her, seeking a declaration of noninfringement. The District Court ruled in the Foundation’s favor. But the Appeals Court sided with Goldsmith, determining that this did not pass the four-fold standard of Fair Use.

The Supreme Court ruled narrowly on just the first of four factors in the Fair Use standard, focusing on character and purpose. Was the work’s character commercial or not-for-profit, and do the original photograph and the Warhol share fundamentally the same purpose?

Their ruling may seem appropriate. This was a licensing agreement. Both Warhol’s Orange Prince and Goldsmith’s own photograph of Prince did grace the covers of magazines commemorating the musician in 2016. This is Warhol at his most blatantly commercial.

But believing that the commercial nature of this project narrows the ruling is a mistake. What elements of today’s art world escape commercialism?

Art Beyond Capitalism?

Alternative rulings exist only in our illusory ideal of artists as untainted by capitalism.

The myth of the Bohemian artist developed alongside the rise of capitalism for precisely this purpose: to create the illusion that art and artists could exist outside the forces of market capitalism.

Starving in their garret studios, Bohemian artists could produce their creative visions at a remove from the “real” world as long as they don’t sell their work or get “discovered” until after their death.

To be a successful artist who receives institutional affiliation or sells artwork in the nascent art market would suggest having sold out. Suffering on the margins and being misunderstood made the artist.

“Bohemians: The Glamorous Outcasts” by Elizabeth Wilson

As art historian Elizabeth Wilson describes, this Bohemian myth was designed to obscure the untenable position of the artist in the age of capitalism. When the growing artistic profession exceeded the limited state-supported positions available in the nineteenth-century art world, artists were forced into the market to survive.

Today some artists find refuge in academic positions or foundation support.

However, in the United States, where the federal government does not directly support artists and art education is chipped away, most artists are market dependent. In this context, the ruling effects any artist who hopes to sell their work and survive as a professional.

Is a Warhol Prince a Portrait of Prince?

The second criteria the court considered was purpose. The ruling asserts that both images are portraits and serve the same illustrative purpose.

Judge Kagan’s dissent suggested her colleagues did not see the obvious transformations found in the Warhol. The judges were not swayed by stylistic transformation. They cautioned against creating a “celebrity-plagiarist privilege,” merely because this was recognizably a Warhol.

No one wanted to look too closely at art, capitalism, and their entanglements. Publishing a photograph of Prince and publishing a Warhol “Orange Prince” are not the same thing, as Condé Nast clearly knew. After all, they paid $10,000 to Warhol’s estate for his image, while People magazine paid Goldsmith only $1,000 for her cover photograph of Prince.

Condé Nast did not simply present Prince on their cover, they presented Warhol. They presented their history of having had the prescience to commission a Warhol. They published Warhol’s transformation of Prince from awkward individual learning the rituals of publicity into an image, secure in the realm of celebrity. Warhol’s print signaled this new “iconic” status. Putting this icon on the cover of Condé Nast set the magazine apart.

Warhol’s art is fundamentally about images under capitalism.

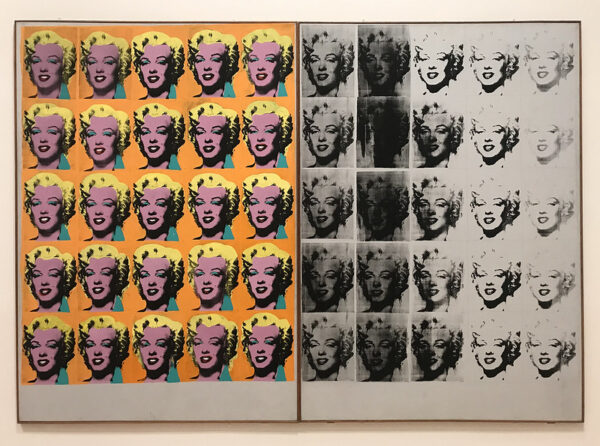

Images, he tells us, gain power through circulation, reproduction, and transformation. Warhol’s famed Marilyn Monroe silkscreens, based on a publicity photo for her 1953 film “Niagara” by Eugene Kornman, are not portraits of Marilyn Monroe.

Publicity portrait of Marilyn Monroe as Rose Loomis in the 1953 film “Niagara.” Photo by Eugene Kornman on Wikimedia Commons.

They are images of Monroe that tell us about her transformation into an icon, consumed as both a brighter-than-life, technicolor celebrity and a tragedy. They tell us very little about Norma Jeane Mortenson. They are about the media, society, and obsessions with celebrity.

Warhol’s acts of appropriation take commercial culture from the realm of mass consumption and transform it into art. He uses changes of scale, color, context and a stylistic signature to signal its new status in the realm of elite consumption. Yet it would be a grave mistake to imagine that such transformation removes art from the capitalist system.

“Marilyn Diptych” by Andy Warhol, 1962. Photo by Rob Corder on Flickr.

A Goldsmith photo of Prince does not mean the same thing as a Warhol print of Prince. It is not worth the same amount in cash or in the cultural capital Condé Nast trades to establish its status. It does not serve the same purpose.

Only in the most mechanistic reading is a Warhol celebrity image merely a portrait.

Chilling Effects

The Supreme Court decision uniting eight of the court’s liberals and conservatives should not surprise.

The Supreme Court and copyright laws have been designed to protect capitalism and those artists who learn to navigate the market. This is why those arts most transparent about their commercial nature such as the film industry wrote amicus briefs supporting Goldsmith. This decision carves out a portion of Warhol’s licensing proceeds for the image’s originator.

In contrast, art museums filed briefs supporting the Warhol Foundation. Their work navigating the line between non-profit status and commercial bottom lines just got much more complicated.

This decision will have a chilling effect on art making where appropriation has long served as an important part of visual communication — a central argument in Justice Kagan’s dissent.

Looking closely at how capitalism operates, how artists function within capitalism, and how capitalism itself generates meaning and value in art are not skills the justices have been trained to do.

This narrow ruling will be difficult to contain as we come to come to terms with just how capitalist in character the art world is and test judges’ ability to see past superficial readings of art’s purpose.

Jennifer Jolly is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Art History at Ithaca College, where she teaches Latin American Art History, ancient through contemporary. She researches Mexican art and politics and has published essays on Mexican Muralism and photographic appropriation in Art History, the Art Bulletin, the Oxford Art Journal, and elsewhere. The recipient of multiple Fulbright-García Robles Fellowships, she completed her prize-winning book, “Creating Pátzcuaro, Creating Mexico: Art, Tourism, and Nation Building under Lázaro Cárdenas” (2018), with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship.