Because a number of my maternal ancestors settled in South Butler, New York, and surrounding communities in the first decades of the 19th century, I have mused on any possible connections between my family and the social ferment bubbling around them.

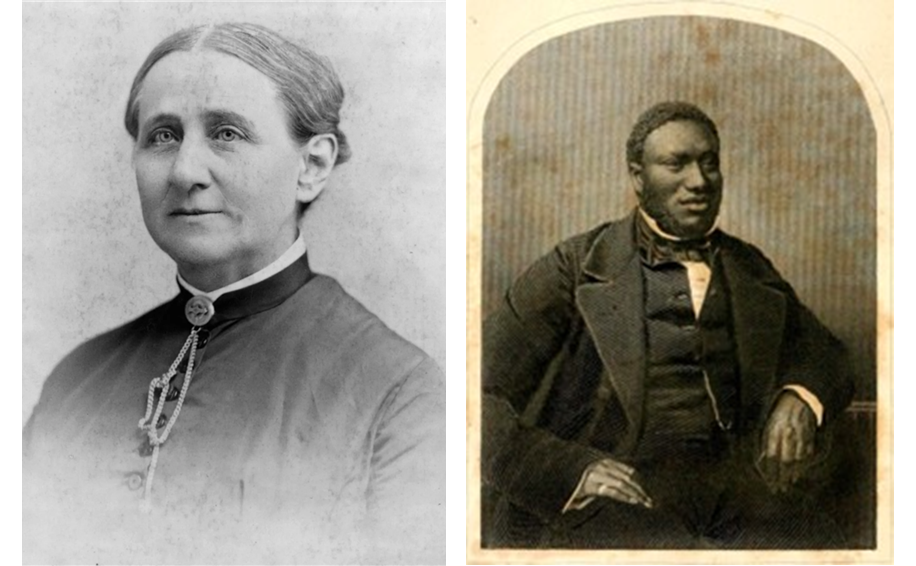

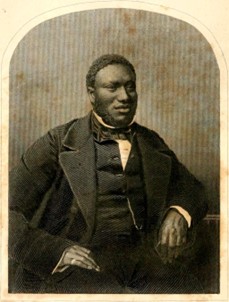

In the course of writing about the political and social tumult in the area during the antebellum period, I focused on two remarkable people. Samuel Ringgold Ward was the first African American ordained in a mainstream American protestant church, and who was pastor for two years, from 1840 to 1842, for the South Butler Congregational Church.

The other figure was Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first woman ordained in a mainstream American protestant church and who also preached for the South Butler Congregational Church a decade after Ward left.

Frederick Douglass knew them both and spoke highly of them.

When he came to catalogue the many allies he found among abolitionists, Douglass wrote, “nor must I omit to name … Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown, for when the slave had few friends and advocates they were noble enough to speak their best word in his behalf.” Of Samuel Ringgold Ward, Douglass said that “as an orator and thinker he was vastly superior, I thought, to any of us, and being perfectly black and of unmixed African descent, the splendors of his intellect went directly to the glory of the race.”

Evidence exists in church records of some of South Butler’s neighboring communities to support Douglass’s claims on behalf of Ward’s oratorical prowess.

Samuel Ringgold Ward

The whole area was aflame with the passions of social unrest and progressive agitation.

Not only South Butler’s Presbyterian Church, but Presbyterian Churches in Rose and Sodus splintered in the two decades before the Civil War. Samuel Ward was instrumental in the secession of the Sodus church from the Geneva Presbytery, which was itself excluded from the General Assembly of the national Presbyterian Church in 1837.

At the heart of all the ferment in eastern Wayne County was the question of human rights: rights for enslaved Black people and for women.

Ward served as Moderator for the rebel Sodus church, which formed in October of 1843. They left a record of the meeting during which secession was formally agreed upon, and the record speaks to Ward’s influence and importance:

“That at 10 oclock greeably to previously appointed Elder Samuel Wyse being present, on being invited addressed the assembly from Zech. 2-5. The meeting being closed with prayer by Elder Greenfield of Williamson adjourned to meet after a recess of one hour.

“After the Council was dissolved the Chh and Congregation were exceedingly delighted in listening to a discourse from Br. S. Ward (2 Cor 6-17) in which the right, cause, necessity, time, and manner – of Secession was made to appear not only to harmonize with what was, now being done by this body, but exceedingly plain as the only pathway of duty illumined by the brightness of eternal truth for Christians to walk in who would cooperate with God in this reformatory age.”

The two biblical texts, which, in typical liturgical fashion, came one from the Old and one from the New Testaments, resonate with the Sodus congregation’s peculiar situation.

The first suggests the degree of isolation felt by the congregation and testifies to their belief in their fulfilling God’s mission, “For I, saith the Lord, will be unto her [Jerusalem] a wall of fire round about, and will be the glory in the midst of her” (Zechariah 2:5). The second, read and explicated by Ward himself, could easily be made to support the abolitionist’s cause, “Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate, saith the Lord, and touch not the unclean thing; and I will receive you” (2 Corinthians 6:17).

McIntosh’s “History of Wayne County” (1877) describes the Sodus schismatics in some detail:

“FREE CONGREGATIONAL. This society was organized October 11, 1843. It consisted of thirty-four members. They held that the local Presbyterian church was involved in the guilt of slavery by its relation to slave-holding churches represented in the General Assembly, and to such an extent that they could only free themselves from responsibility in the matter by an independent society.

Rev. Samuel R. Ward, then of South Butler, was moderator of the council, and preached the sermon. Rev. David Slie was secretary.”

The major discrepancy between the seceders’ own declaration and McIntosh’s later version concerns Ward and Slie.

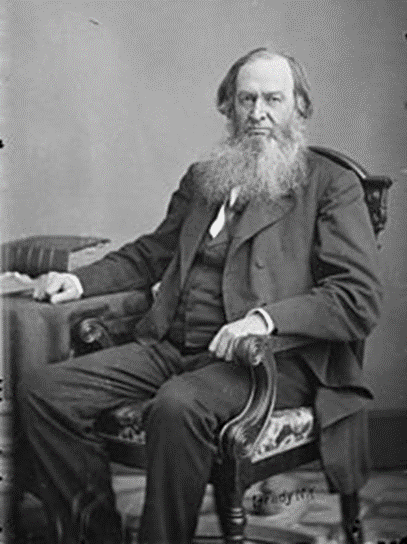

Gerrit Smith

David Slie, the Secretary of the dissenting members of the Sodus Church, was apparently an itinerant revivalist preacher and, according to the 1843 document, was installed in South Butler. My guess is that he came to fill in Ward’s place after Ward fell ill.

In 1835 Slie was rebuked by the Presbytery of Angelica, in the southwestern part of New York, for doctrinal errors and for preaching heterodoxy. Slie was apparently a member of the Black River Association, a loosely organized Congregational evangelical association which targeted dissatisfied Presbyterians

The charges against Slie indicate that his activities remained constant through the decade after his expulsion from Angelica.

“Landmarks of Wayne County” (1895) elaborates on the schism Levi Gaylord’s family traced back to French Huguenots. Levi was the first of his family to settle in Wayne County. He emigrated from Bristol Connecticut. Gaylord “was a graduate of Yale, came to Sodus in 1823, and engaged in the practice of medicine. He was known throughout the State as one of the leading Abolitionists and temperance workers of the day.”

Antoinette Brown Blackwell

Throughout the ’40s and ’50s both the Sodus and Rose Presbyterian churches and the Congregational schisms from them exchanged documents and heated charges and countercharges with the authorities of the Geneva Presbytery.

And South Butler continued to play a role in the upheaval.

In March of 1850 the Rose church made a formal offer to James Gregg, who was then in the pulpit of the South Butler church, to assume the ministry in Rose.

He did so only on condition that the Rose church distance itself from the Geneva Presbytery because, as he put it, he “could not unite in examing & receaving those who wished to unite with such a church as that would imply a countinancing of the principal of sustaining a church relation to a known & acknowledged sin” (James Gregg, letter to Rose Church, March 11, 1850, Wayne County Archives).

The known sin being slavery.

David DeVries retired from Cornell University where he served as associate dean for undergraduate education in the College of Arts and Sciences. He has a life-long fascination with the Finger Lakes and western New York, particularly its nineteenth century history as the so-called “Burned-Over District.” This fascination stems partly from the fact that his mother’s family had settled in South Butler and the Wolcott area in the first decade of the nineteenth century. This piece is adapted from a longer work entitled “Reading the Slates,” a cultural memoir.