Myriad films across the history of Latin American cinema explore the trope of the migrant.

These films document the trek from Latin America to the U.S. and migrants’ lives afterwards. Classic films such as “Espaldas mojadas” (Alejandro Galindo, 1995) and “El Norte” [The North] (Gregory Nava, 1983), to more recent ones such as “Maria, Full of Grace” (Joshua Marston, 2004), “Entre nos” [Between Us] (Paola Mendoza, 2009), the documentary “Al otro lado” [To the Other Side] (Natalia Almada, 2005), and the award-winning feature “Babel” (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2006), represent this trope.

Other films such as the Spanish production “Princesas” [Princesses] (Fernando León de Aranoa, 2005), the Colombo-Canadian production “La Playa DC” (Juan Andrés Arango, 2012), and the Ecuadorean feature “Rabia” [Rage] (Sebastián Cordero, 2011) portray migration stories to Canada and Spain.

With different perspectives and narrative foci, these films expose the realities leading to migration, the difficulties of the journey north, and inhospitable life after departure. In many films the main characters triumph and learn to live in a new place, a new language, a new culture. In these narratives, protagonists discover new worlds. These films insist that those in the Global North realize their own complicity in the tragic unfolding of migrants’ lives.

However compelling, the ideology of the so-called “American Dream” winds as an undercurrent. With narratives showing the improbability or impossibility of its attainment, these films justify the struggles of migrants. They assume the only choice for people outside the Global North is to emigrate to the United States.

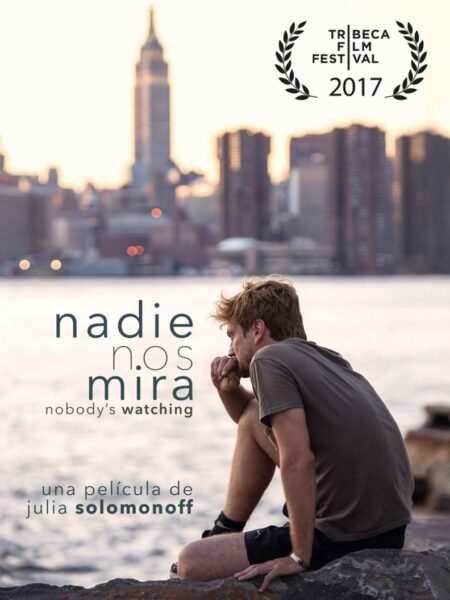

In the Argentine film “Nadie nos mira” [Nobody’s Watching] (Julia Solomonoff, 2017), a formerly famous Argentine telenovela star, Nico, leaves his success behind to search for worldwide acclaim working in U.S. film production. Seeking international stardom and trying to escape a toxic relationship with one of his Argentine telenovela producers, he leaves for the United States to find a new life. Yet at the end of the film, Nico is unhappy with his life in the U.S. and returns to Argentina.

In the last scene, Nico is in a theater in an urban setting, living a fulfilling life. Is he in New York? Or Buenos Aires? He is certainly in Buenos Aires. But the film creates ambiguities. The images of a cosmopolitan metropolis outside the Global North might be unfamiliar for some viewers who might assume he still resides in New York. Why leave the U.S.? Who would choose that option? Why return to Latin America?

Enter the narratives of return.

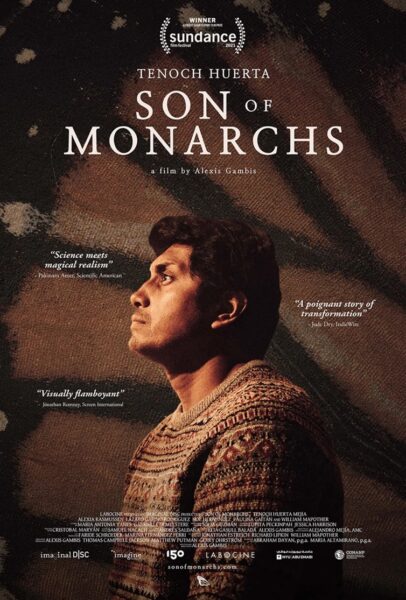

For the last several years, a number of Latin American films complicate this Latin American migrant trope. Films such as “Hijo de monarcas” [Son of Monarchs] (Alexis Gambis, 2020), “Ya no estoy aquí” [I’m no longer here] (Fernando Frías, 2019), “Sin señas particulares” [Identifying Features] (Fernanda Valadez, 2020), and “Nadie nos mira” mentioned above, among others, fashion narratives of migrants returning to Latin America after time in the U.S.

These films unwind more nuanced views about why people leave and why they return home. They break the binary opposition between the blissful “American Dream” and the dark, oppressive, and impossible “Mexico-filter-y” life migrants seek to escape. Films such as “Traffic” (Steven Soderbergh, 2000) popularized this Mexico-filter by toning scenes in Mexico and the Global South with sepia. They represent scorching-hot, stark, dry, dusty deserts and spaces. Often featuring violent and despairing images, this filter functions as a short-hand for stereotypical representations of the Global South. In contrast, films of the return break this visual logic, generating new paradigms about place and home.

Narratives of return propose a complex process envisioning different ports of departure and terminus. They position home and place generously. Even if dystopic, they imagine life in Latin America as a possibility.

“Nadie nos mira” (Julia Solomonoff, Argentina/U.S., 2017)

“Nadie nos mira” is a story of migration and return. Nico, the main character, is unusual due to his privilege and precarity. He is a white or white-passing, blonde, and blue-eyed Argentine television star who migrates to the U.S. to work with a hip young Latin American director who cast him as a protagonist in his new film. While Nico waits for investor backing, he works as a waiter and serves as a de facto au pair to his friend’s baby. Nico uses the baby and stroller to steal from pharmacies and grocery stores. To make extra cash, he spends his days swindling. In the long wait for the film to commence shooting, he overstays his visa and becomes undocumented.

The director informs him that investors prefer other actors. Nico tries to make it in New York, but is rejected from acting jobs for not being “Latino” enough. He hides his new undocumented and financially precarious identity from old friends and family. Nico had a love interest who could have helped him remain in the U.S. through marriage and a green card. But Nico is romantically attached to his former producer who has a family and considers Nico a diversion.

Nico’s in-between status applies to both his undocumented displacement and his queer identity. Although Nico’s privilege and visibility inform his final return to Argentina where he can secure theatrical work, his decision to return is daring. It defies the typical migrant narrative that figures Latin America as a landscape of loss. Nico’s return imagines a new Latin American future of possibility and hope.

“Sin señas particulares” (Fernanda Valadez, Mexico, 2020)

“Sin señas particulares” portrays a more traumatic and dark return to Latin America. The narrative focuses on two protagonists, a mother, Magdalena, and a young man, Miguel. They travel in opposite directions. Magdalena travels to the north of Mexico to find her son, Jesús, who disappeared while journeying to the U.S. for work. Miguel, close in age to Magdalena’s son, has been deported back to Mexico from the United States. He journeys south to his home to find his family.

These two protagonists find each other in a lawless, violent, and dark borderland. Their lives entwine. Magdalena finds a surrogate son in Miguel. Miguel finds a surrogate mother in Magdalena. In the film’s denouement, Magdalena learns about the gruesome deaths of the people in a bus traveling north, the same bus her son Jesús traveled on. A Zacateca indigenous elder, the only apparent survivor, recounts the people on the bus died in the hands of the devil, personified by a group of rank-and-file criminals in a northern Mexico cartel. They stopped the bus and killed everyone.

Heartbroken, Magdalena reaches the end of her quest. Miguel travels to his rural home to find it abandoned. Magdalena asks Miguel to live together and build a new life in her home. Before their journey south, the narcos catch them and kill Miguel. Magdalena discovers that Jesús, her biological son, executed Miguel. He is the devil described in the Zacateca elder’s story who turned evil to prevent the narcos from killing him. Jesús informs Magdalena he will find a way to send money and that she should forget him. As Jesús transforms from victim to executioner, “Sin señas particulares” paints a dystopic despairing narrative of return.

“Hijo de monarcas” (Alexis Gambis, Mexico/U.S., 2020)

“Hijo de monarcas” is a visually exhilarating and poetic film. Mendel, a Mexican immigrant in New York City, is completing his Ph.D. in biology. The film oscillates between explaining Mendel’s past and present and showing the deep connections between the human and natural worlds. Mendel studies monarch butterfly wing pigmentation, an insect he remembers from his youth. Flashback sequences show monarch butterflies surrounding him and his brother in a lush forest in Michoacan, Mexico.

The monarch butterfly has a long history as a symbol of migrants. It travels back and forth across the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The film ponders a migrant identity that imagines borders as porous and non-existent, connecting the plight of migrants to environmental catastrophes. As children, Mendel and his brother lost their parents after the exploitative practices of a mining company flooded their hometown.

As a result, Mendel has a tense relationship with his home and brother. When he returns after the death of his grandmother, his brother rejects him. For her wedding, his niece asks him to be the padrino, which translates as godfather but here means something closer to best man. He returns to confront his past. During the wedding preparations, his brother reveals that he saved Mendel from the flood during the mining incident. Despite this heroism, he feels Mendel abandoned him. The two make amends, suggesting a metaphoric return.

The film continuously jumps between past and present, Mexico and the United States. It advocates for a deeper connection to the natural world, a radical political gesture proposing both a borderless world and a more porous border between human and nature. Mendel extracts pigment from the butterflies in his lab so that a tattoo artist can draw wings on his skin just like the monarch. At the end, Mendel attends an indigenous ritual with animal masks and costumes in Mexico with a long-time friend, suggesting humans can find answers in the natural world.

The trope of the Latin American migrant is not over. Cinematic narratives chronicling Latin American mobilities across the world reveal continuously changing intricacies. Films like “Nadie nos mira,” “Sin señas particulares,” and “Hijo de monarcas” present daring reimaginings of home and place.

Latin America is no longer a place to leave behind but a space to imagine a possible future of hope, despair, return. A space to once again call home.

Camilo A. Malagón is Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures and Codirector of the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Minor program at Ithaca College. He writes on late 20th and 21st century Latin American literature, film, and culture, focusing on theories of space, place, and globalization. His research also includes ecocriticism, world literature, and critical theory. He has published and has articles forthcoming in Studies in Spanish and Latin American Cinemas, Revista de estudios colombianos, and A contracorriente. He recently co-edited a dossier on contemporary Colombian cultural production.